Tales from the Mythology & Us

Sometimes, the mythology that resounds with us the most reveals much about where we are in life. How we interpret the ancient stories reveals more about our internal struggles than the motives of the authors who lived thousands of years ago. Mythology is a fascinating topic that has captivated people for centuries. It is the study of traditional stories, legends, and folklore that have been passed down from generation to generation.

While many may believe that mythology is a relic of the past, it is still very relevant today. Firstly, mythology helps us understand our cultural heritage. Every culture has its own unique set of myths and legends that define its identity. These stories provide us with a glimpse into the beliefs, values, and customs of our ancestors. Secondly, mythology can help us understand ourselves. Many of the stories found in mythology are allegories that explore the human experience. They can provide us with insights into our own fears, desires, and struggles. For example, the story of Icarus (or Jatayu, that which we will see in detail) warns us about the dangers of hubris and the consequences of ignoring sound advice.

Thirdly, mythology can inspire us to greatness. Many of the heroes and heroines in mythological stories exhibit qualities such as bravery, wisdom, and compassion. These stories can inspire us to strive for these same qualities in our own lives. For example, the story of Hanuman teaches us about the value of perseverance, loyalty, and the rewards of hard work. Fourthly, mythology can help us make sense of the world around us. In today’s complex and rapidly changing world, it can be difficult to find meaning in the events that shape our lives.

Finally, mythology can help us connect with others. The stories we tell and the myths we believe in are an important part of our shared cultural heritage. By sharing these stories with others, we can build connections and foster a sense of community. In a world that often seems divided, mythology can help us find common ground and build bridges between different groups.

They say mythology was initially used to communicate ideas that the proponents of civilization felt were crucial for their citizens to understand and incorporate in their lives. As it has been demonstrated, there are more lessons that can be taught from mythology than just history or philosophy. These stories are powerful and interesting, and have concepts and ideas that can be studied that one might not initially realize. Such a story as Icarus (Or that of Jatayu), is one of the first references to man attempting a long flight.

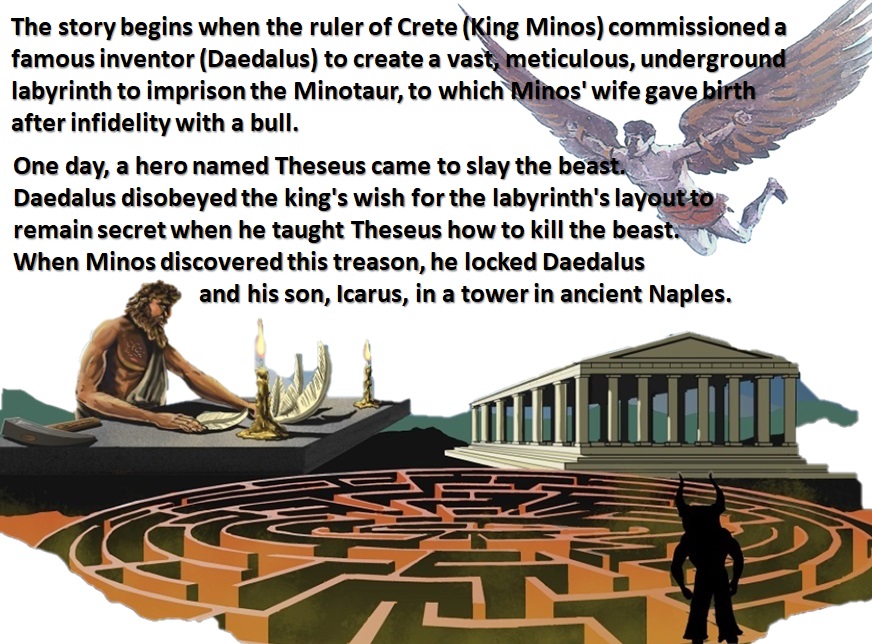

Icarus: Greek Mythology

Daedalus looked for a way to break out of imprisonment. There was no escape at sea, which was dominated by seafarers who were loyal to Minos. The land crawled with Minos’ soldiers. Daedalus saw only one option for escape: the air. Daedalus gathered feathers from the rocky shore and used hot wax to create a structure in the shape of wings. When one pair successfully carried him into the air, he created another pair for his son and taught him how to fly.

Lessons to Take Away from Icarus

The traditional moral of the story is to beware ambition because risks can lead to unexpected consequences; however, there are far more lessons to be learned from Icarus.

A) Ambition Is Not Always Rooted In Pride: . . . Why did Icarus fly so high? Perhaps it was because he wanted to know what it would be like to touch the sun. Or maybe he flew too high purely by accident – simply enthralled by the pleasure and exhilaration of the flying— the wind in his hair and the sun warming his face– and forgot to pay attention to where he was going. Maybe he was chasing a high, longing to experience what he thought the ecstasy of that warmth would feel like after being locked away in a cold stone tower in the dark for such a long time.

B) Escape Takes Many Forms: . . . Icarus was trying to escape from a violent fate on the island of Crete. For some freedom is merely physical. Icarus was no longer trapped behind bars or locked in a tower, but he still wanted more.

C) Being Passionate Towards Achieving Our Dreams: . . . Icarus was passionate. He gave his life to achieve his dreams. To him, reaching the sun was worth any cost. It made him forget everything else. The sun was the only thing that existed for Icarus, and he had no desire for the rest of the world. One can imagine that, as he fell from the sky, he could only stare longingly back at that ill-fated star and admire its beauty. We can all think of being in love with our goals like Icarus loved the sun.

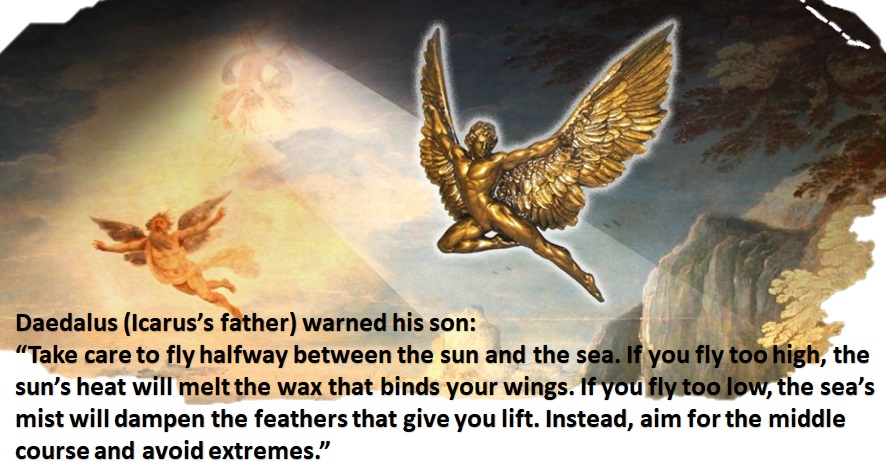

D) The Importance Of Listening To The Wisdom Of One’s Elder: . .

However, Icarus was exhilarated by his newfound power of flight. He soared high into the heavens, ignoring his father’s warning. Daedalus (Icarus’s father) was a master craftsman and an accomplished inventor. Icarus’s ignoring of his father’s warnings resulted in his death, which is a not-so-subtle warning to the youth of the society. There was no room for disobedience and disrespect of one’s elders in our mythology. We should always revere our elders and heed their advice, before we go our own way.

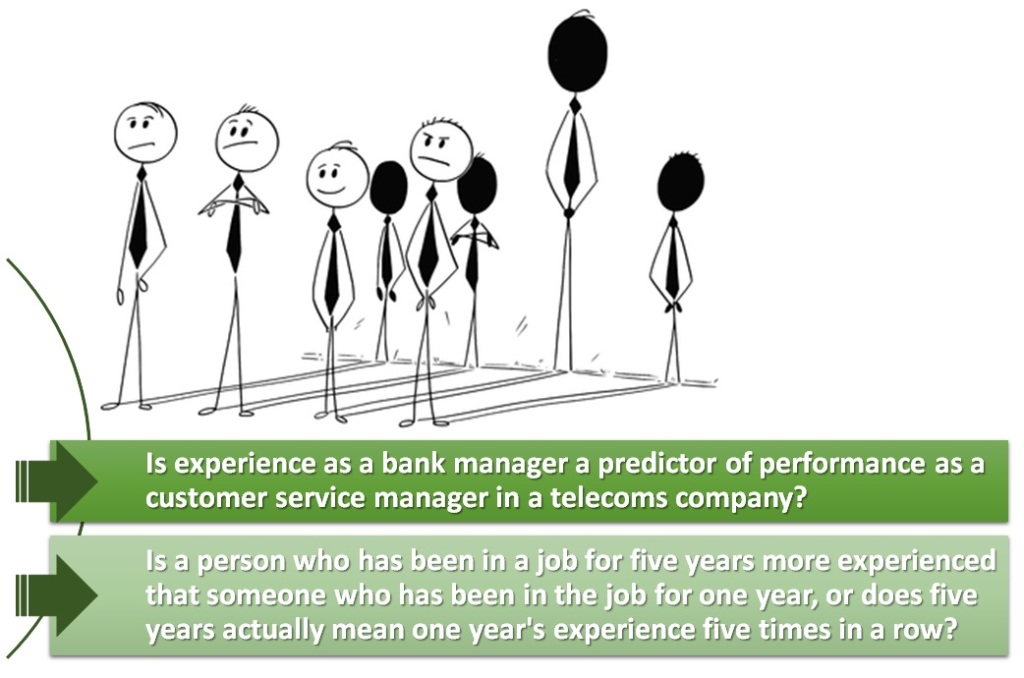

E) Understanding One’s Limitations (Or) The Limitations Of One’s Situation: . . . Icarus let the sheer exhilaration he felt from the act of flying distract him from the limitations of his wax wings. We often let the exhilaration of various activities and the sense of youth and a future distract us from the fact that we are still very much mortal and it could all easily end. We have to define what exactly is too far or too much for us in order to know how much we can achieve without negatively impacting ourselves. Setting boundaries means specifying to the people in our life what we can give and share, but also what we need from those relationships.

F) Failure Is Not Something To Be Feared: . . . Maybe Icarus didn’t touch the sun, but he got closer than any man ever had before. He breached domain that was thought only to belong to the gods as he conquered the skies. His flight was revolutionary and far beyond what was thought possible for humankind. The road to progress is paved by people who take risks. Perhaps, his flight was enough to give others (prisoners on the island of Crete) hope. Icarus makes us ask ourselves what we would do with a chance to fly.

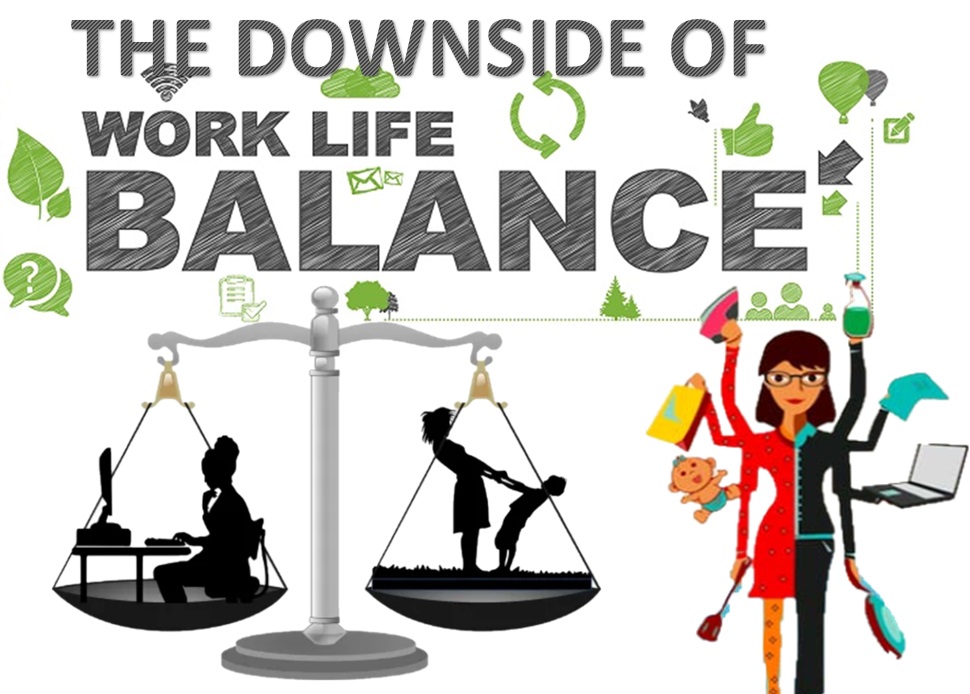

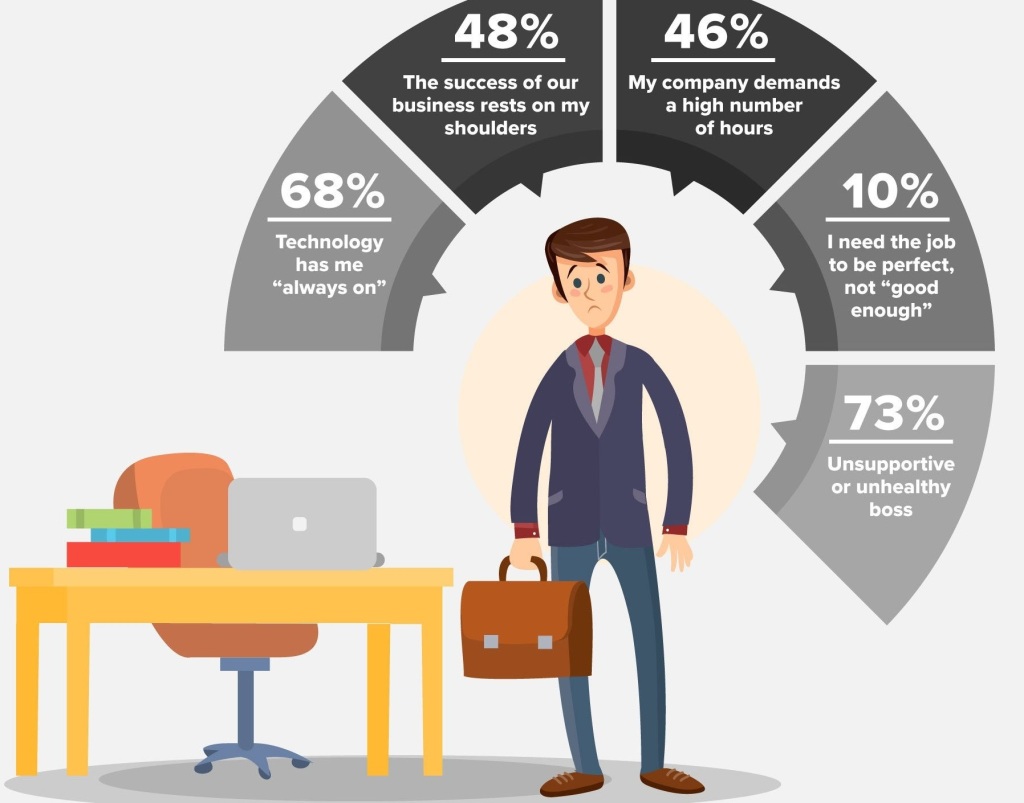

G) Too Much Of A Good Thing: . . . There was nothing wrong with Icarus enjoying the experience of flight. However, he let this enjoyment cloud his judgment. He was only focused on the pleasure of the experience and lost sight of its purpose, his gateway to freedom. Instead, his pleasure brought him crashing down. More often than not, too much of a good thing has unexpected consequences. These can vary from substance abuse having a direct influence on our body to more abstract ideas like too much attention being spent on devices or activities versus one’s loved ones.

H) The Importance Of Being Balanced: . . . This applies to all aspects of our life: physical, mental, financial, social, emotional and spiritual. We should not be too greedy and want everything and neither should we be too fearful and avoid everything. Greed and fear are two emotions that direct lot of what we do. We need to consciously be aware of these emotions as we live our lives and make sure we do not fall prey to either of them.

I) Greed and Arrogance: . . . The newfound ability was too intoxicating for Icarus. His father might have constructed the wings, but it gave Icarus an ability everyone has long dreamt of: Being able to fly. He now had that ability, and understandably, it was a rush. He was excited- he let it go to his head. Ignoring his father’s cries and prior advice, he went higher. Ambition and arrogance outgrew his ability, and he died for it.

J) Being Intoxicated With Ambition: . . . Daedalus (Icarus’s father) built wings for both of them, and he stayed at a safe altitude and flew safely, and that can be contrasted with Icarus’s carelessness. Daring and innovation works just fine if we understand their limitations, but they’ll destroy us if we don’t.

Daedalus was still able to fly perfectly at certain heights. However, it is Icarus who literally got “above his place” and flew too high. Icarus thought that he was the greatest human being, as he was the only mortal who could fly. However, his wings came apart and he crashed into the sea.

The Ramayana- Jatayu and Sampati

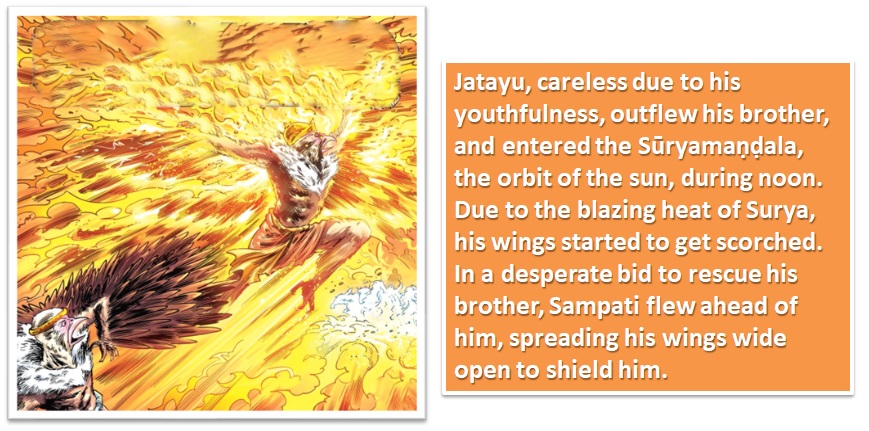

The Indian epic Ramayana contains a similar tale of what happens when you fly too close the sun. Jatayu and Sampati (The sons of Aruṇa & Shyeni) are two demigods in the shape of birds, who also happen to be brothers. During their youth, Samapati and his younger brother, Jatayu, in order to test their powers, flew towards Surya, the solar deity.

As a consequence, it was Sampati who had his wings burnt, descending towards the Vindhya mountains. Incapacitated, he spent the rest of his life under the protection of a sage named Nishakara, who performed a penance in the mountains. Sampati is said to have been enlightened with spiritual knowledge in these mountains by sages, who told him to cease lamenting about his broken body, and wait patiently until he is able to serve Rama. He never met his brother alive again. Sampati, unfortunately, never recovers from this incident, and lives a sad, flightless life in the forest. Although Jatayu’s wings are only partially burnt, he also falls. Eventually, Jatayu is able to recover and has further role to play in the rescue of Princess Sita.

Just like the Daedalus and Icarus myth, the tale of Jatayu and Sampati warns readers not to be reckless or overstep their bounds. But unlike Sampati, Daedalus never tries to shield Icarus from the sun. Because of this, the Indian myth contains a stronger lesson about the importance of sacrificing yourself for others (especially your family).

Finding The Balance in Our Lives

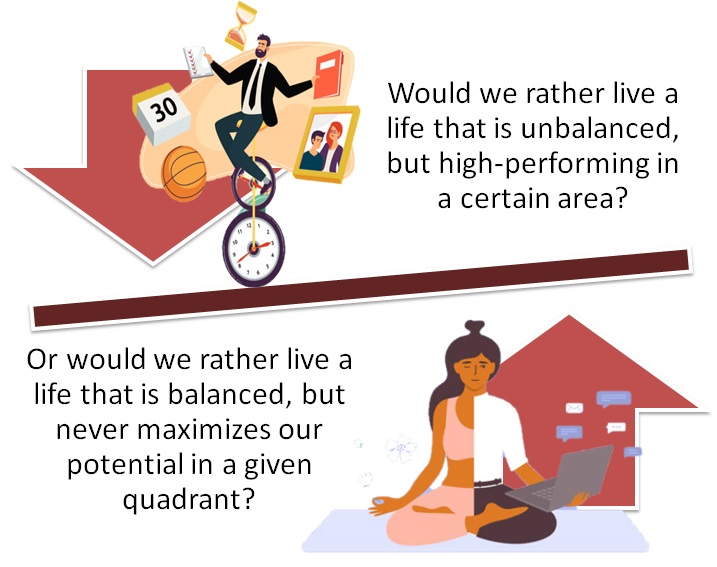

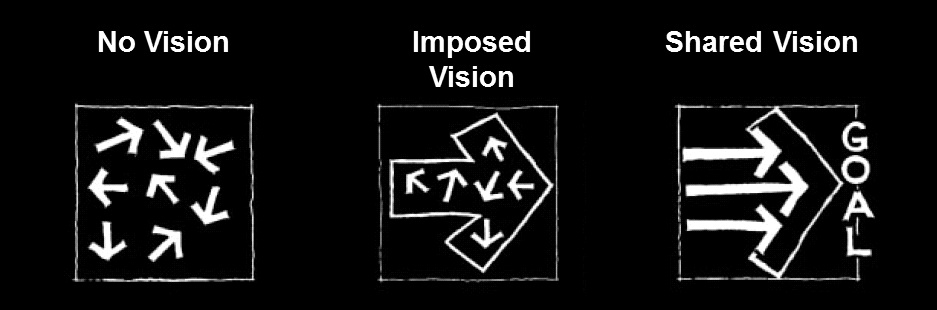

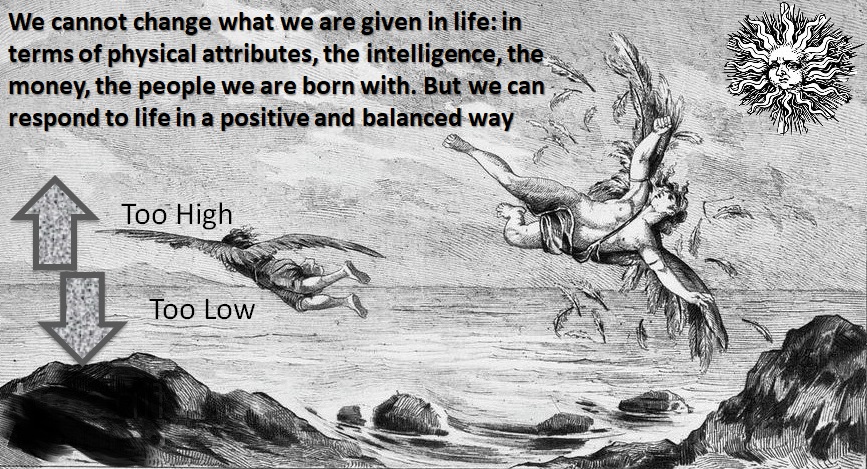

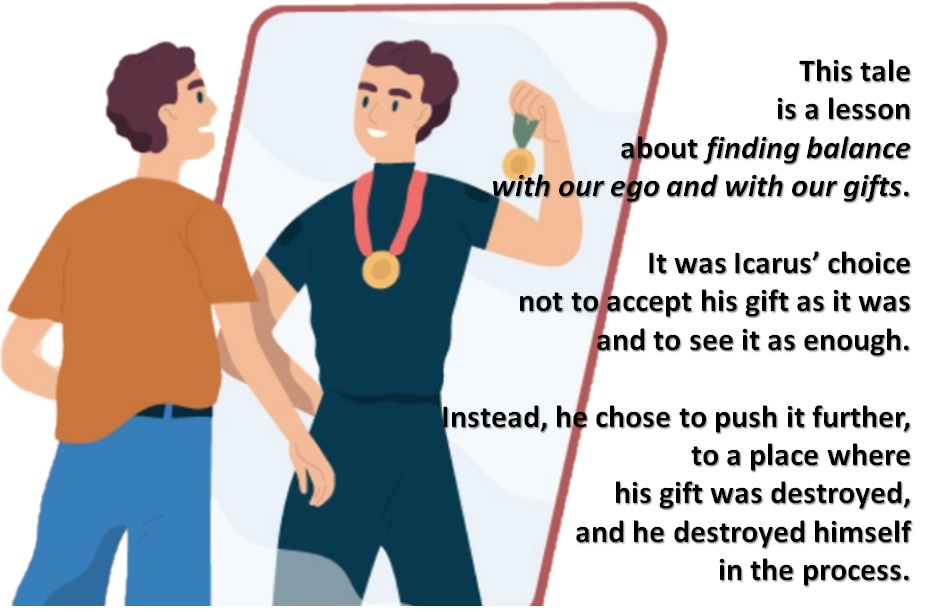

We all have, and are given, wings to fly on and it is our choice what we do with them. Do we not use them and never take flight? Do we accept them as they are and fly proudly on them to new destinations? Or do we misuse them, flying too high, too close to the Sun, destroying our gift and ourselves in the process? If we don’t fly—or try to fly too high like Icarus, the myth teaches us that we will find ourselves falling into the depths of emotional despair, drowning in our egoic feelings (as represented by the sea Icarus drowned in).

To make the most of our gifts, we don’t need to make ourselves into more than we are, you don’t need to fly higher than we can and burn, but we also don’t need to stay down on earth, denying our own wings to fly. Icarus teaches that we have power over what we do with our gifts, and to what heights and destinations they take us.

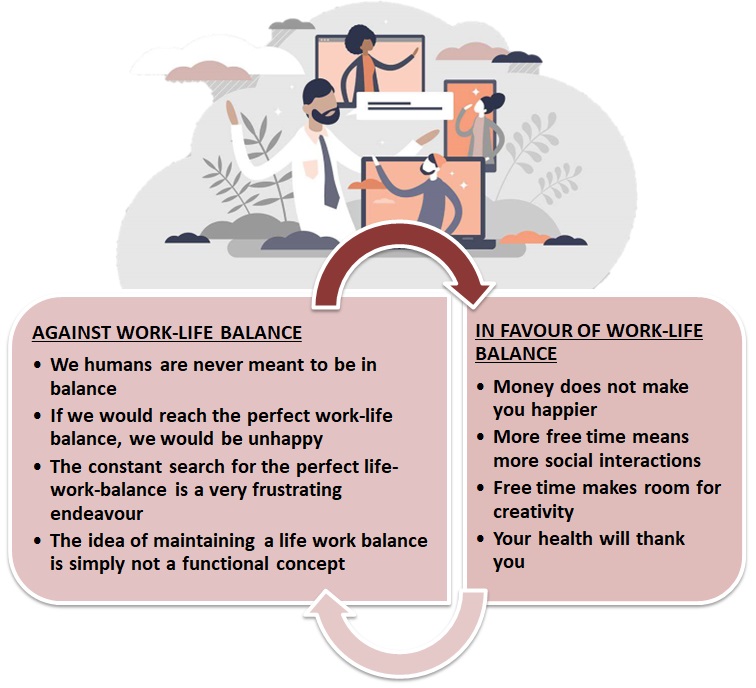

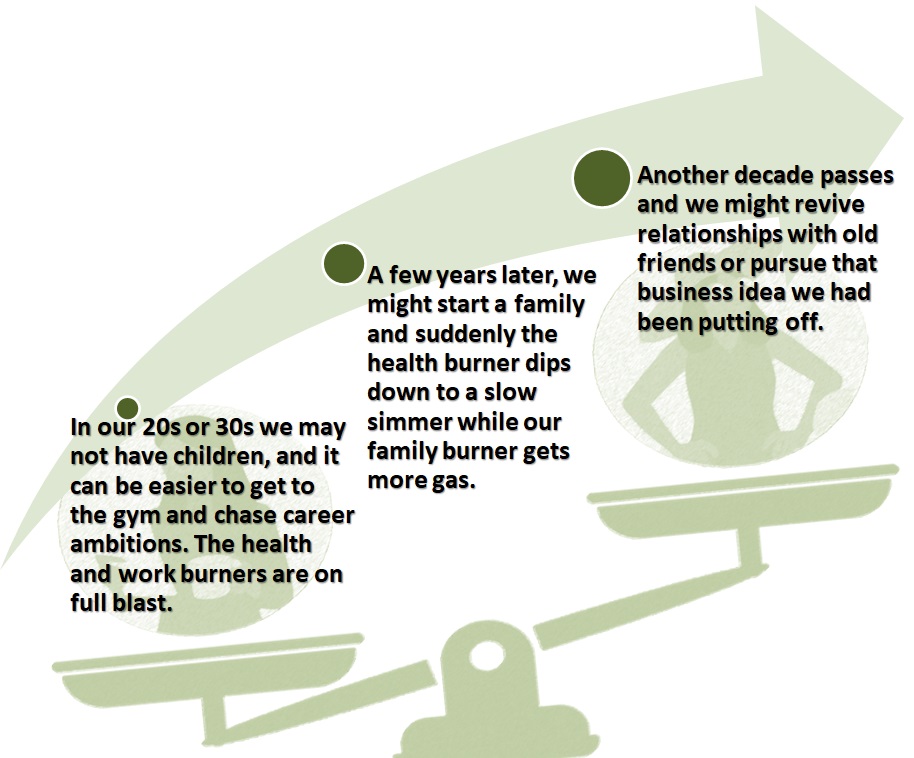

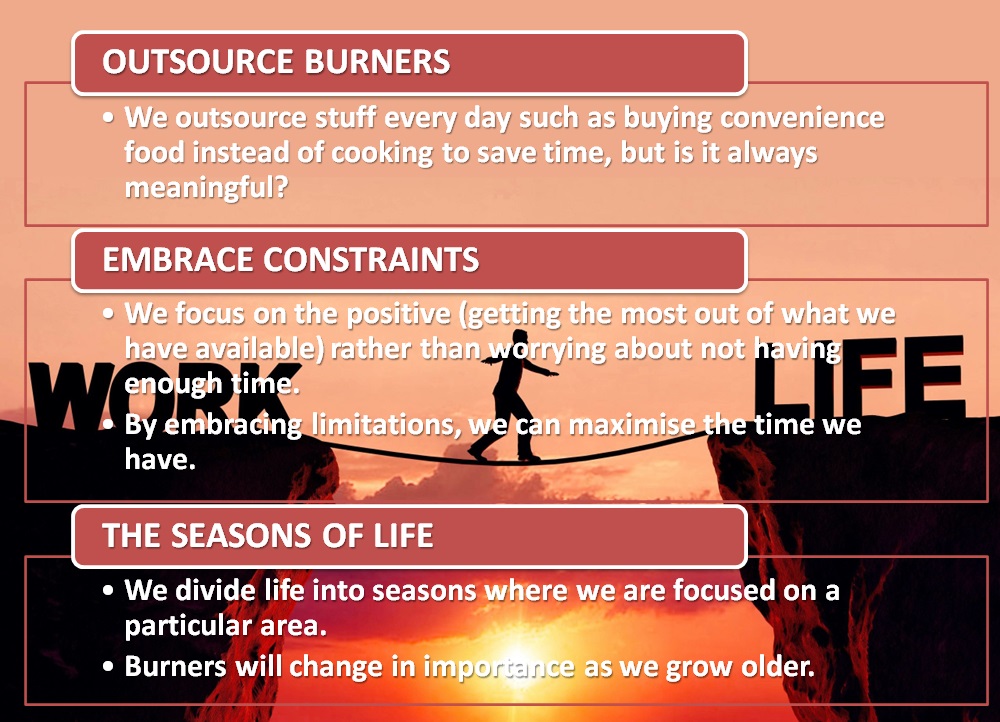

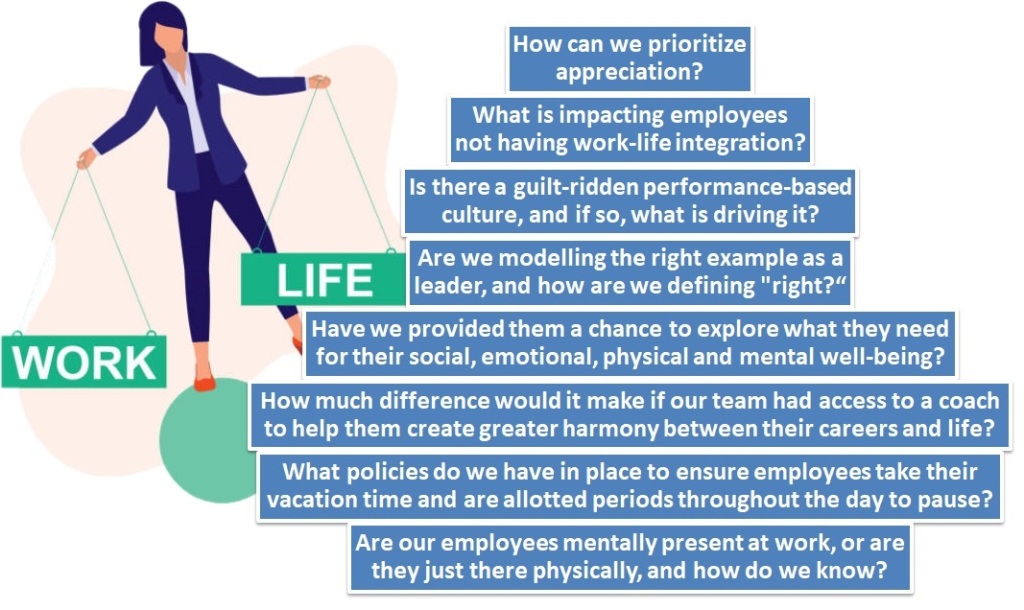

In today’s fast-paced world, finding balance in our lives can be a challenge. We juggle multiple responsibilities and commitments, and it can often feel like we are running on a hamster wheel, never quite getting anywhere. However, finding balance is crucial to our overall well-being.

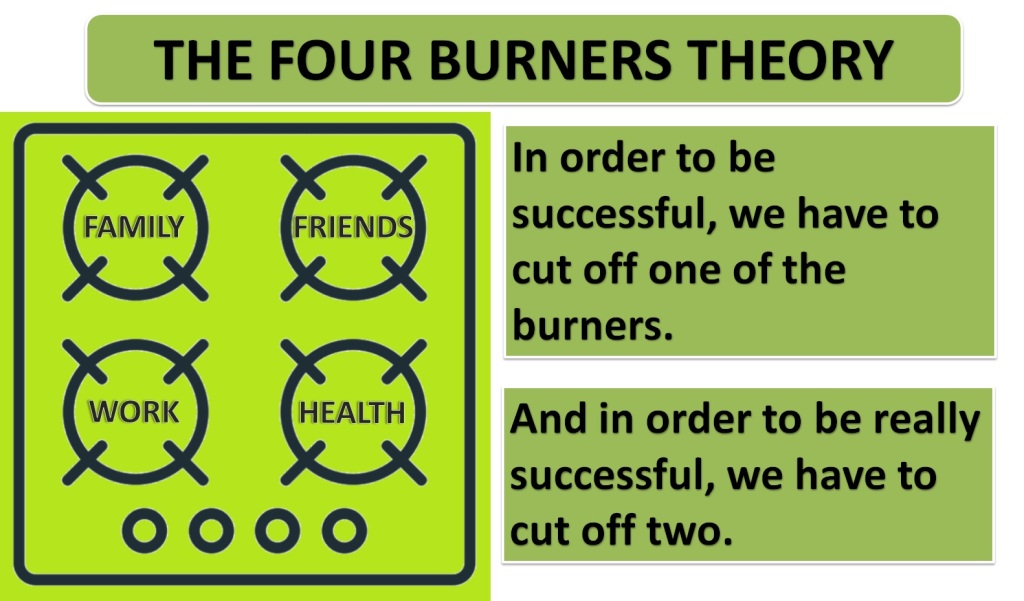

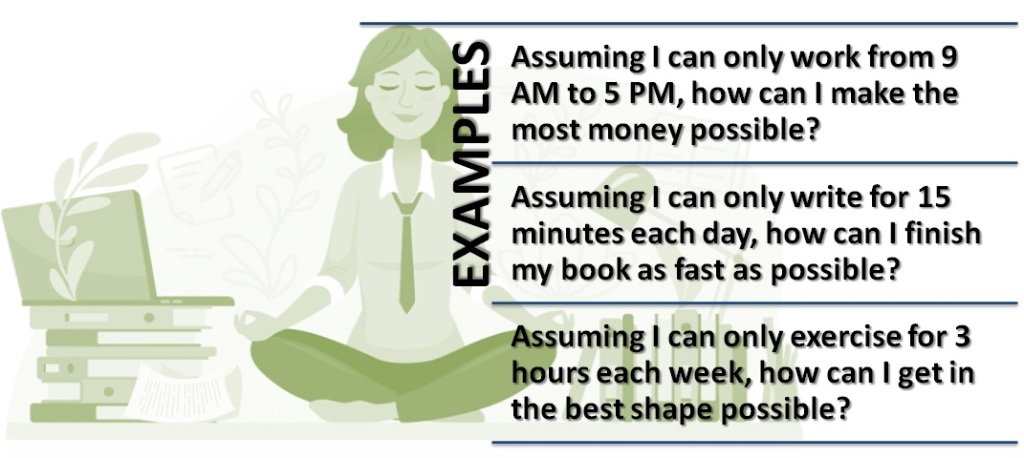

Firstly, it is important to prioritize. We cannot do everything at once, and trying to do so will only lead to burnout. It is essential to identify the most important tasks and commitments and focus our energy on those. Secondly, we need to learn to say no. It can be challenging to turn down requests for our time and attention, but saying yes to everything will only lead to overwhelm. We need to set boundaries and be clear about our priorities.

Thirdly, it is important to take care of ourselves. We cannot pour from an empty cup, and neglecting our own needs will only lead to burnout. Self-care looks different for everyone, but it might include things like exercise, meditation, spending time with loved ones, or engaging in a creative hobby. Finally, it is important to remember that finding balance is an ongoing process. Life is full of twists and turns, and what works for us one day may not work the next. We need to be adaptable and willing to adjust our priorities as needed. We also need to be patient with ourselves and remember that finding balance is a journey, not a destination.

The Two Facets of Living Life

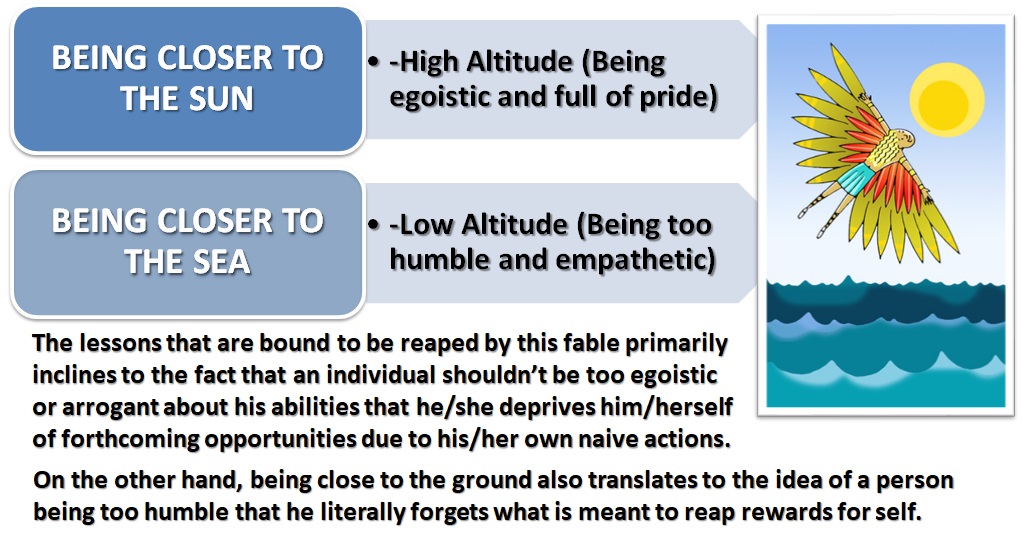

The story of Icarus presents the notion of two facets of living life, namely:

Being too humble has its own disadvantages too because once we start caring excessively about others, they might walk all over us instead of recognizing the generous behaviour. Hence, Icarus’s father plainly exhibits that we shouldn’t fly too high that we forget our roots (else the wings shall melt) and we shouldn’t go too low as it may prove fatal to our overall flight. Either way, it’s maintain balance or be killed.

Content Curated By: Dr Shoury Kuttappa