What is the biggest difference between managing managers versus managing individual contributors? Clearly, it is a question top of mind for many of us, all over the world, who find ourselves promoted or hired into a role where we are not just a manager — but a manager of managers. Is this brand of leadership any different? What should a new manager of managers consider in their role? Do we need to provide Training/ Coaching? And how do we serve as a good role model?

What Does It Entail

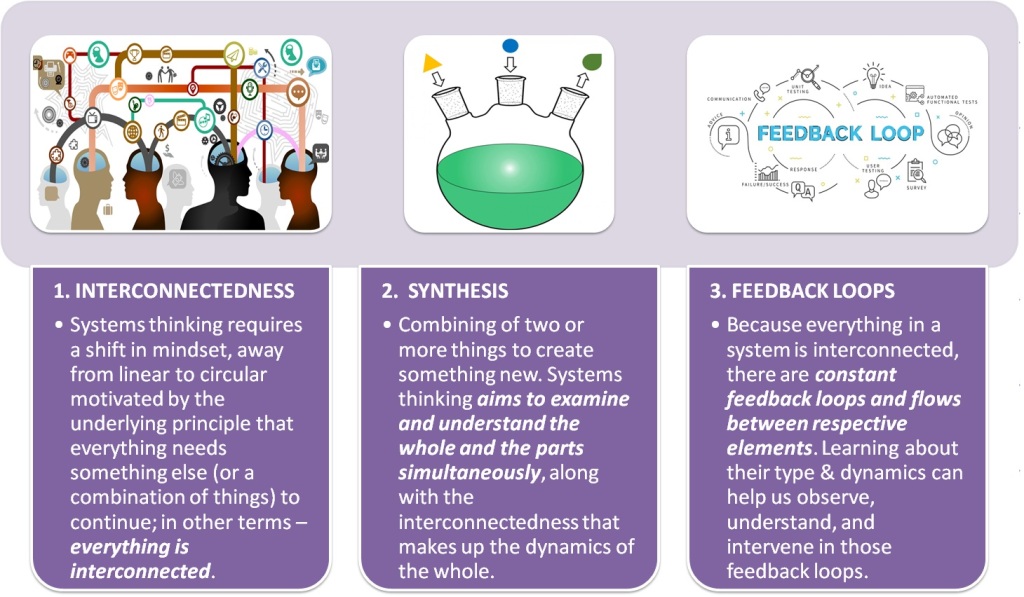

When we are managing managers, our responsibilities are two-fold: we need to make sure they are producing good work (as with any employee) and that they are effectively supporting their teams. We might know how to do the former, but how do we do the latter? In some ways, managing managers is similar to managing anyone else — we need to align their goals with ours, provide feedback, and help them advance their careers, says Sydney Finkelstein, professor at Dartmouth’s Tuck School of Business. But there is one important difference —managing managers also requires leadership coaching. We have to coach managers to develop the culture and capabilities that their team members need, says Linda Hill, professor at Harvard Business School.

What Is The Difference?

This is especially important because moving from an individual contributor to a manager is an often neglected transition. In most organizations, first-time managers do not get a lot of formal training. The critical difference is that the work we are overseeing and supporting is management. Sounds simple, but management is tricky because it is both a technical and a relational skill. As the manager of a manager, we are paying attention to the outcomes that they lead their teams to achieve and how they relate to their staff in the process.

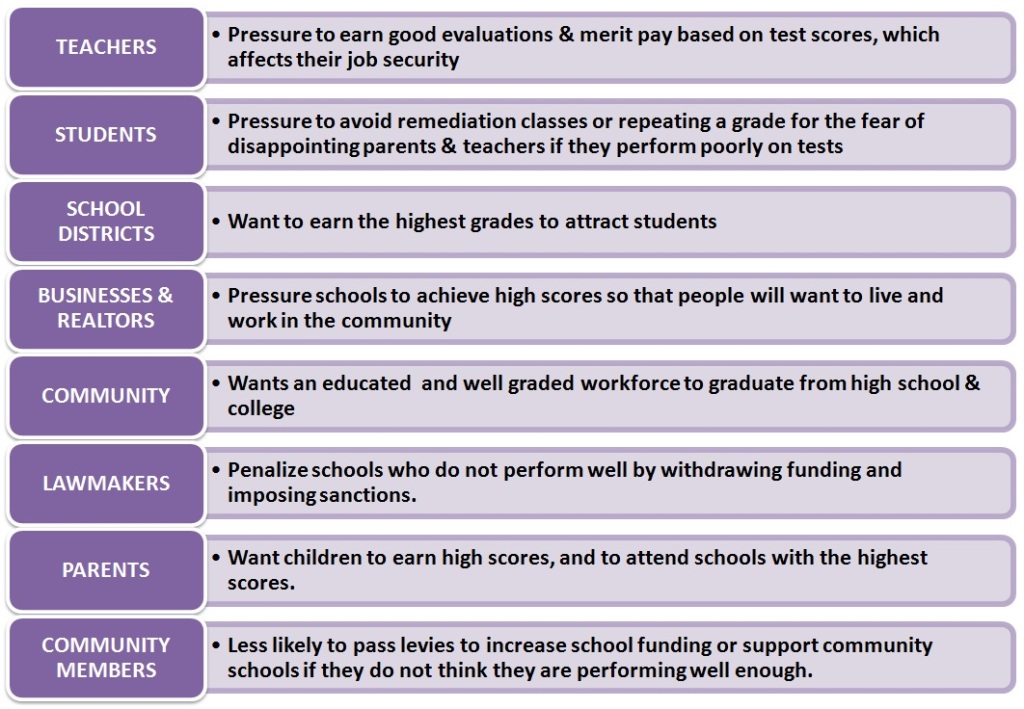

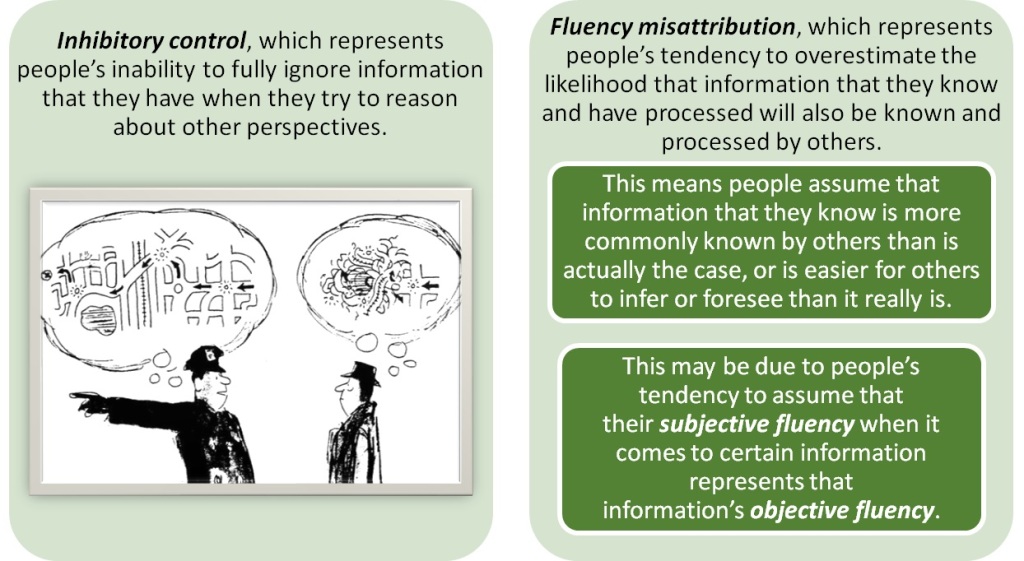

On top of that, in traditional hierarchical structures, the manager/staff relationship has a built-in power dynamic. That is what we call positional power—it is part of our job to help our managers hold this power responsibly. This includes seeking to understand how their other identities (age, race, gender, etc.) and experiences with power and privilege intersect with their role at work. Managing managers requires familiarity with management best practices, adaptability and responsiveness, and keen attention to equity and inclusion.

The Start- Clear Understanding of Manager Job Profile/ Specification

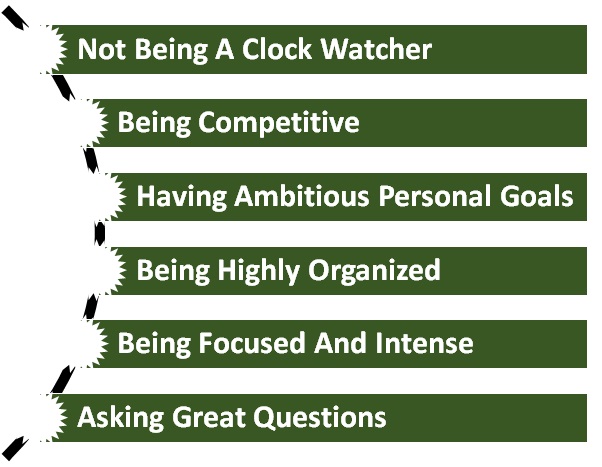

A statement of requirements our business expects from managers for a role is key. These may include Emotional characteristics and Sensory demands (such as making judgements).

Manager positions can differ widely from one organization to another. This requires organizations to provide a clear profile of the traits, skills and qualities for high performing managers. Aligned to the business drivers, this profile clearly specifies what a manager must know, what experiences s/he should have, what s/he can do, and what personal attributes s/he must possess to be a high performing manager.

Managing Managers

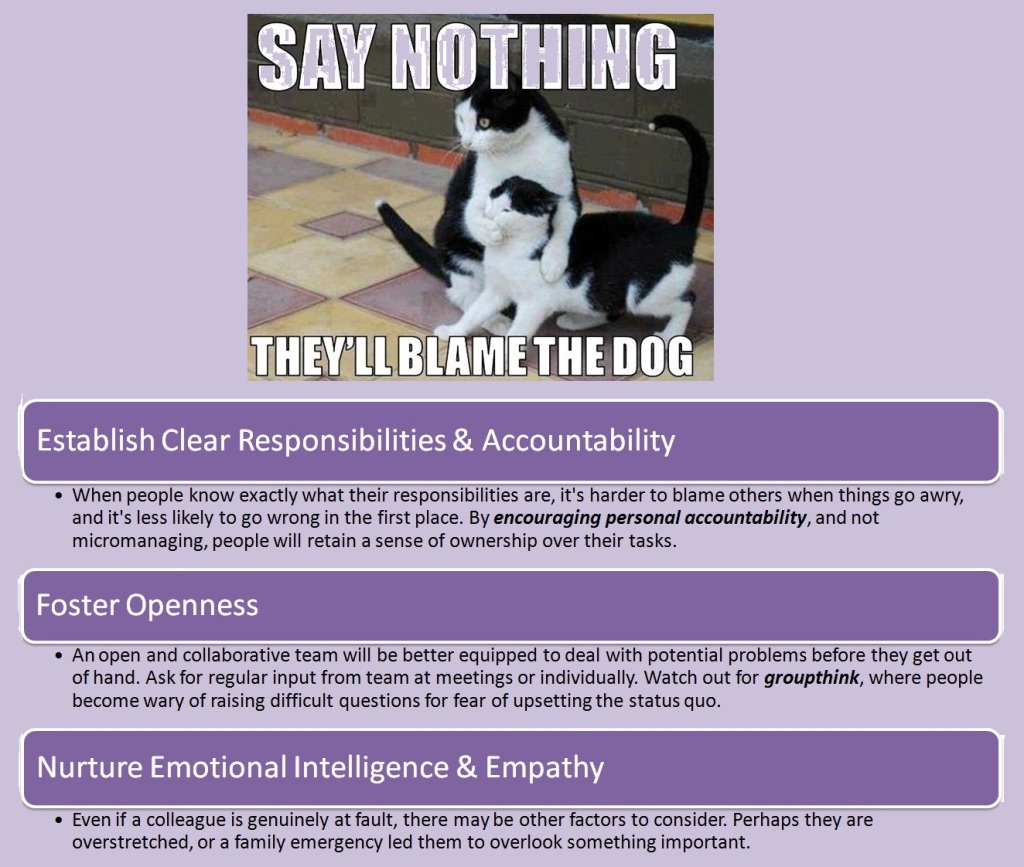

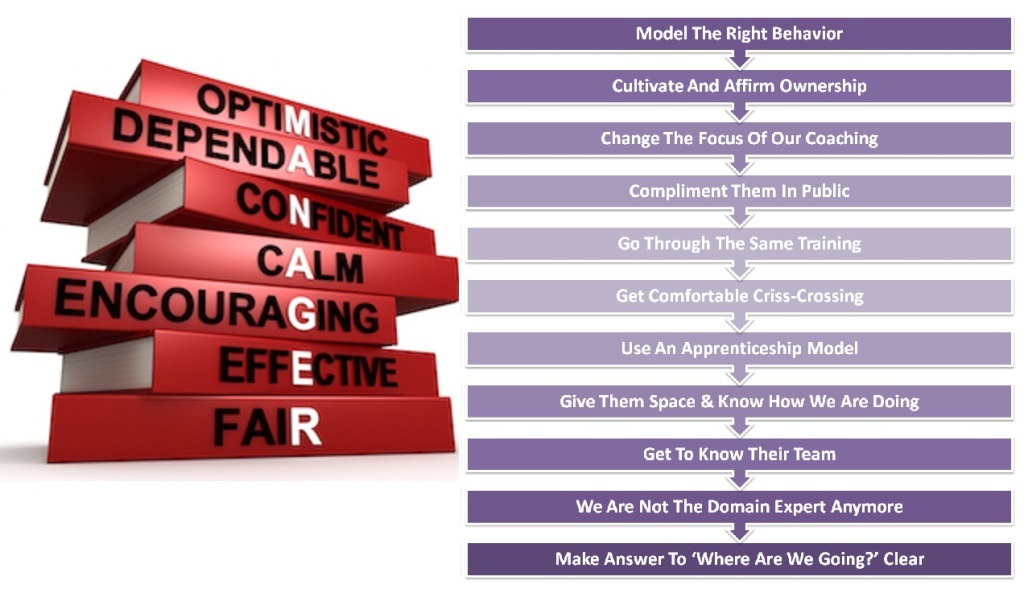

Some ways in which we can fill in the gap and help our direct reports be great managers may be as follows.

- Model The Right Behaviour

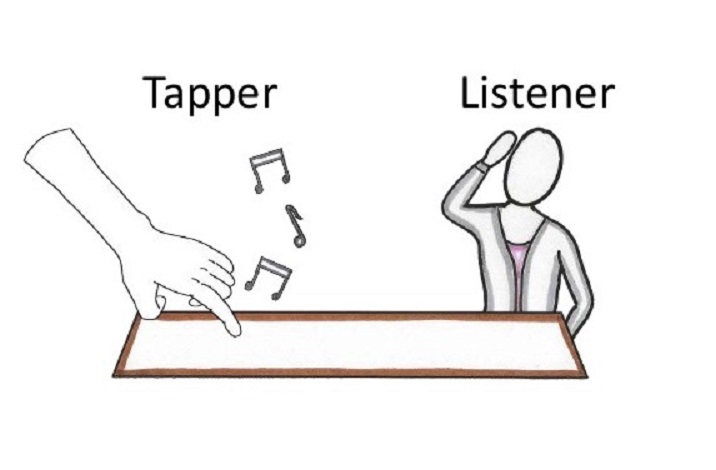

Research has revealed a common theme- people learn how to lead from their bosses. But our direct reports do not just learn from us when we sit down for our one-on-one meetings. It is not particularly authentic to say we are going to be a role model on Thursday from 4 to 5pm. People are watching all the time. Therefore, we need to be managing our people in the way that we expect them to manage their own teams. It is useful to be deliberate and aware that people are paying attention. For example, if we want our direct reports to give their team members autonomy, be sure that we are doing the same for them.

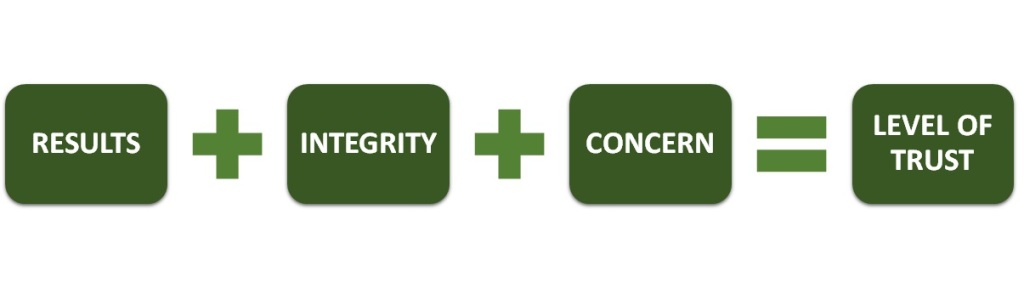

- Cultivate And Affirm Ownership

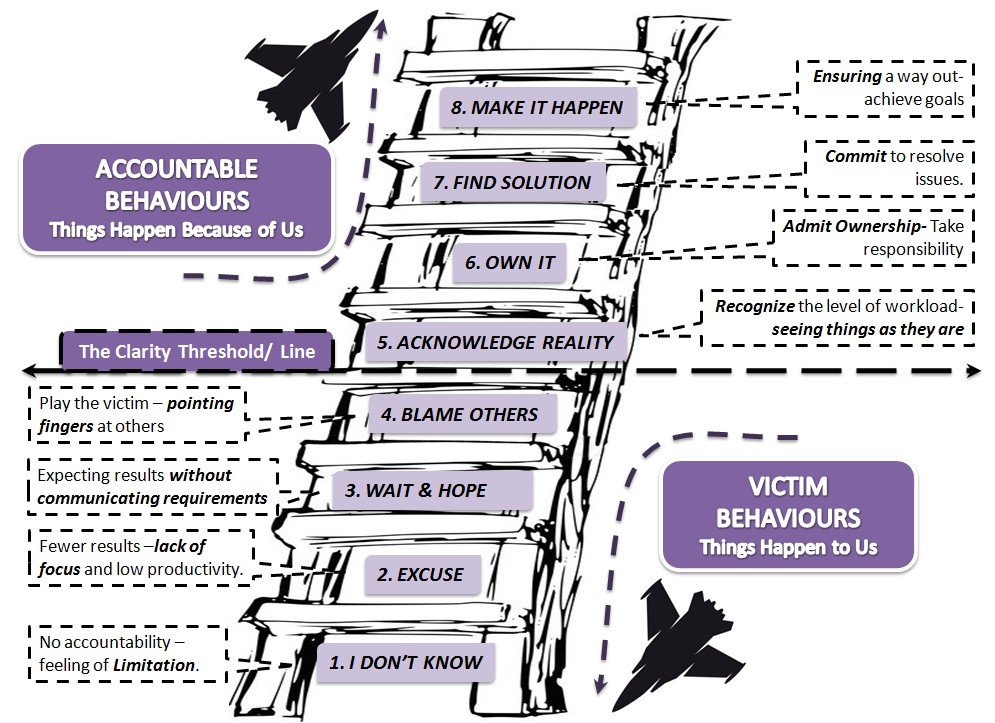

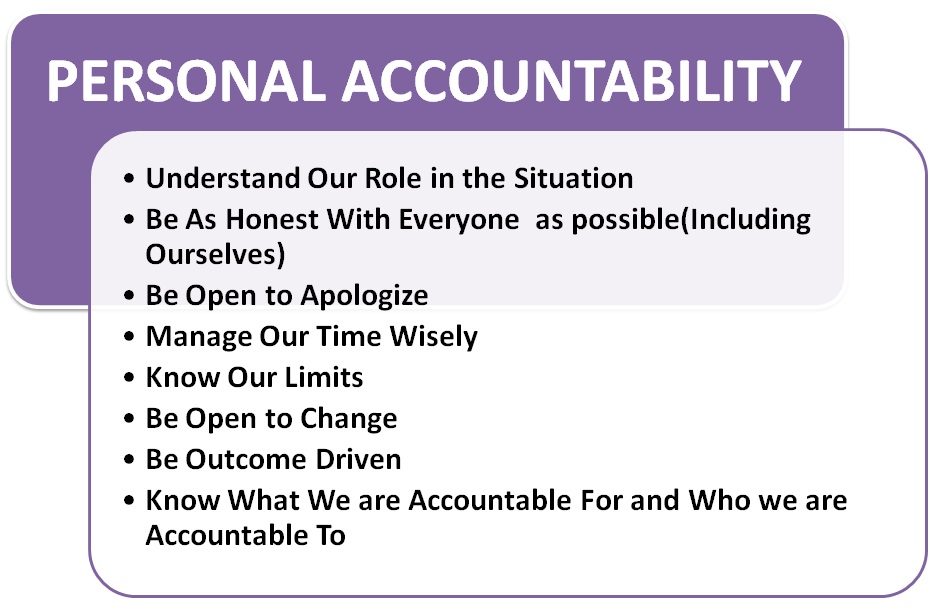

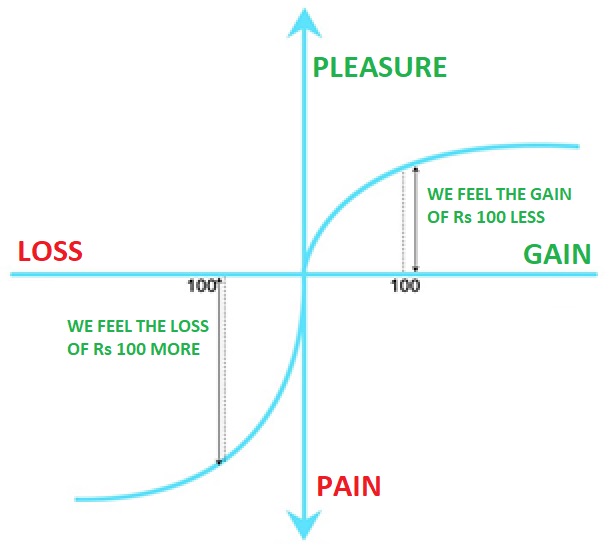

One common challenge for many managers is owning their management– meaning embracing the responsibility that comes with positional power and increased organizational leadership. In most workplaces, positional power gives a manager real influence over the employee’s quality of life at work (how much they’re paid, how they get feedback, opportunities for advancement, their sense of belonging, etc.) and sometimes beyond (references for future jobs). These decisions require context (including knowledge of policies and ongoing bias checks) and a sense of responsibility for one’s authority.

Additionally, when we are a manager, we are not just on the hook for our performance and our work—we are responsible for supporting someone else. This requires skill in coaching, delegating, and holding others accountable, where a manager’s approach can shape staff experience.

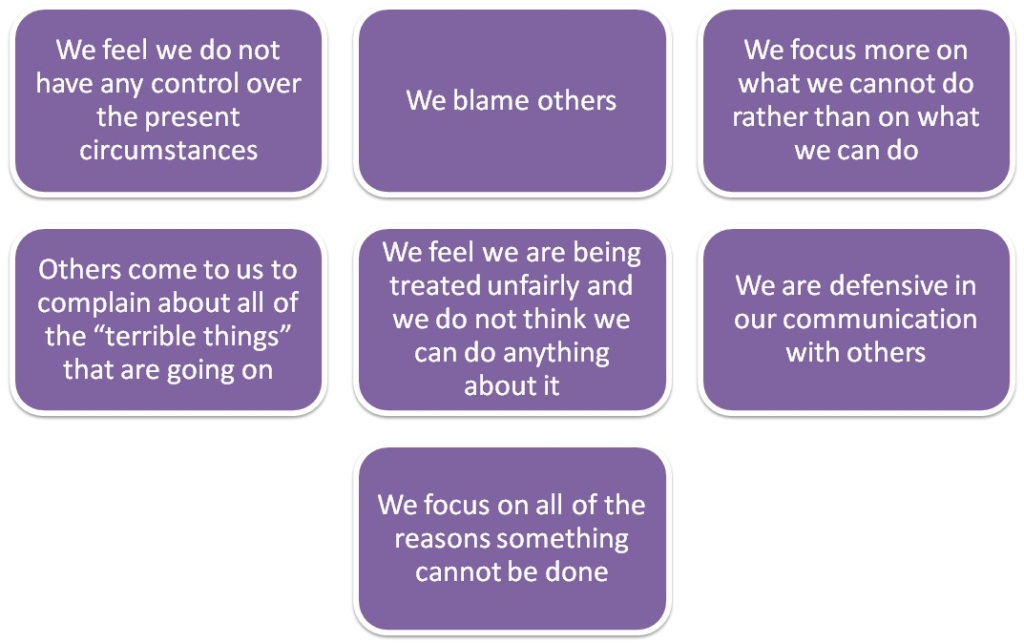

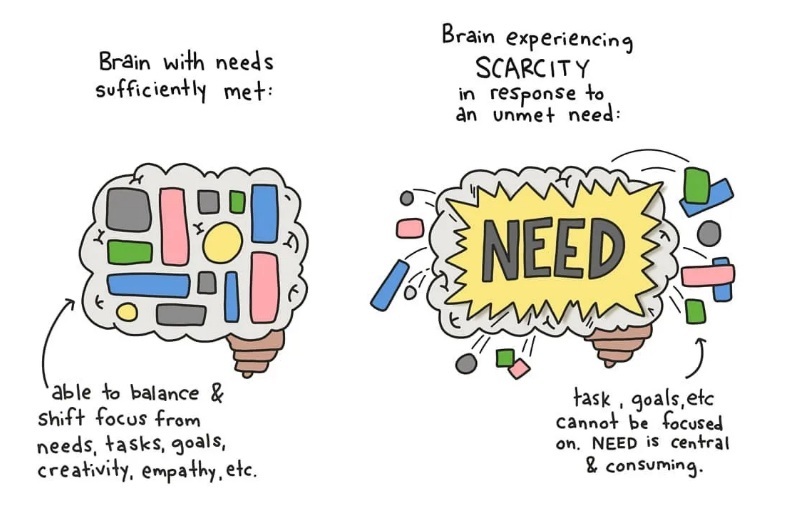

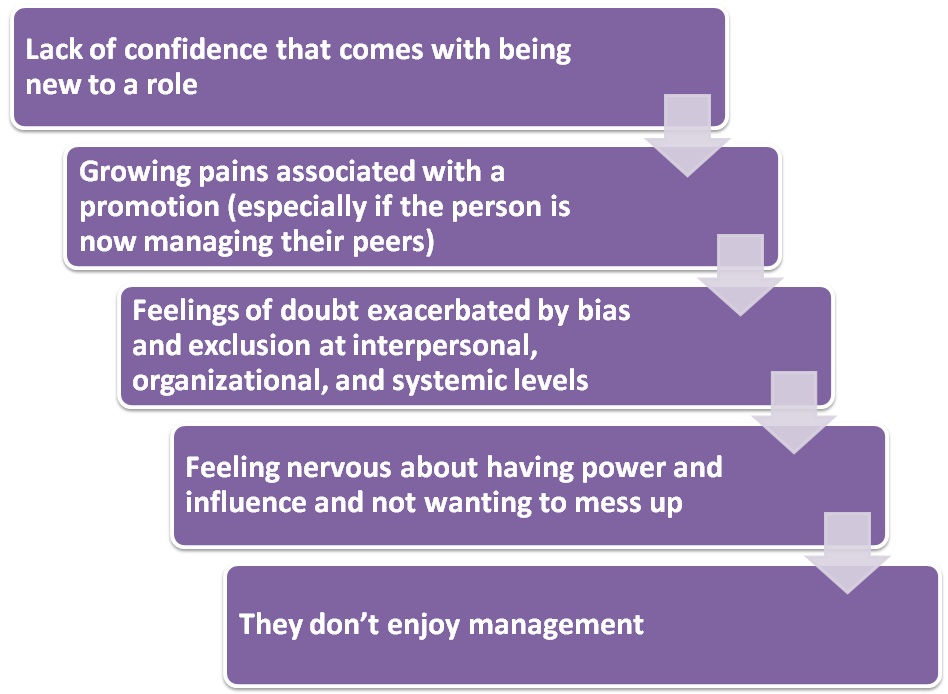

Finally, managers can also have an outsized impact on the stress levels, emotional health, and sense of belonging of their teams (even when they don’t mean to), which is even more complicated when managing across lines of difference. While many managers struggle with owning their management, authority, and influence, the “why” behind it may vary. Here are some possible reasons:

Whatever the reason, the managers we manage will benefit from the time we invest to cultivate and affirm ownership over their sphere of influence, which is a core competency for their role.

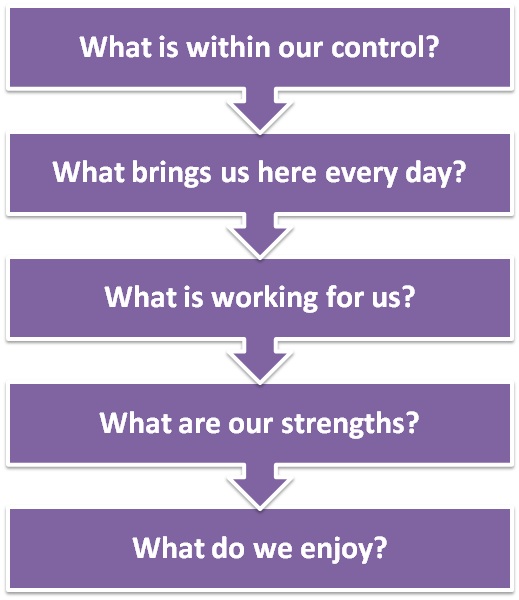

- Change The Focus Of Our Coaching

We spend time with our individual contributors talking about the specifics of their work but with managers, we will also need to explore their relationships with their direct reports. Instead of asking, “How’s that project going?” we might ask “How are you working with XXXX to get that project done?” or “How might you better support XXXX on that project?” The aim is to talk directly about how they are coaching and giving feedback. This sends a signal that these things are important. We may ask them how much time they are spending on coaching since they might be tempted to overlook this, and we might regularly remind them that we all have a responsibility to develop people.

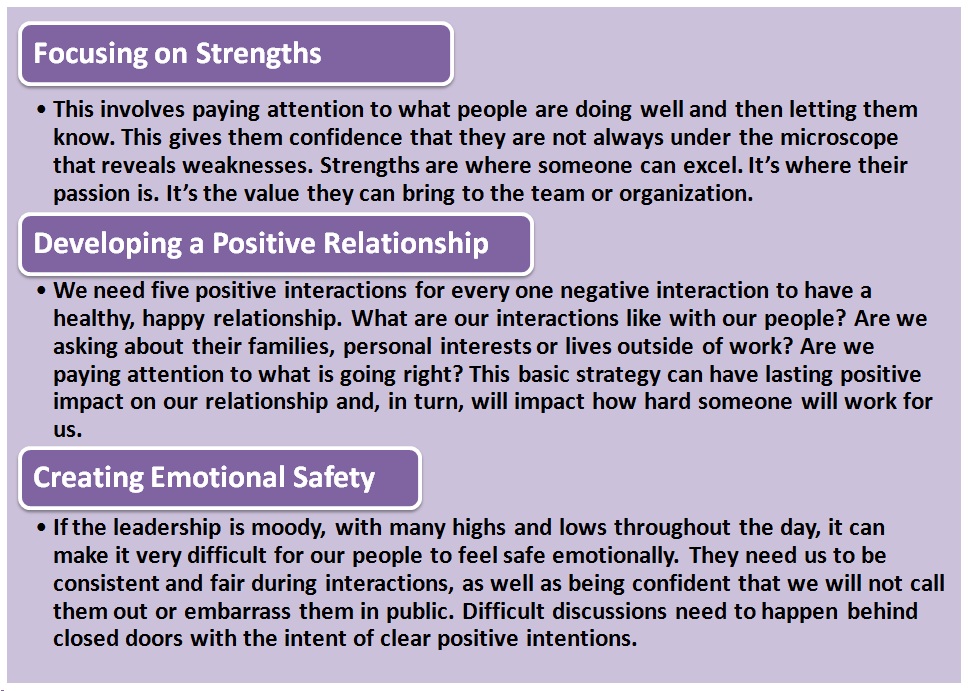

- Compliment Them In Public

The people who report to our direct reports look to us for clues as to how they should feel about their managers. If we respect the person and the job he/she is doing, they will too. The aim is to give people opportunities to demonstrate their credibility in front of others. When we show that we value someone on our team and their direct reports are watching, it can really help. Some ways are praising them publicly, asking for their advice in front of others, or assigning them part of a presentation that lets them show off their expertise. Also we need to be careful as the same effect can work for negative comments. If we have criticism to offer, we must be sure to do it privately.

- Go Through The Same Training

Some organizations offer formal training for new managers or send up-and-coming leaders to executive education programs. Really good executive learning programs teach a common language (way of doing things) and that can be really valuable for us and our direct report. If we participated in a class that we found particularly helpful, suggest that our managers do the same.

- Get Comfortable Criss-Crossing

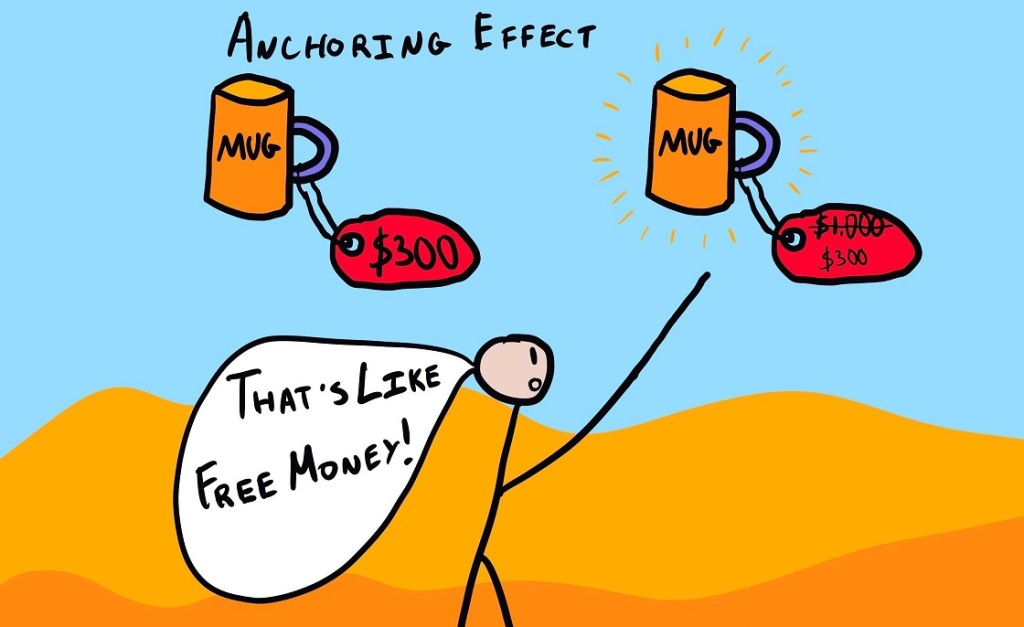

When we are managing managers, our focus is much more cross-functional — we are working with business units across the entire organization, instead of just one or two. There is a popular misconception that we get more freedom and control the higher up we go. But the reality is, when managing managers, our freedom and control is contingent on more moving pieces. We have more stakeholders to consider and more departments to coordinate with. We may have the final word on more things and greater scope than when we were only managing individual contributors, but now, as a manager of managers, our view of the pie — and our responsibility of the pie — is bigger.

***To be continued in Chapter 02 (Managing Managers- G/ H/ I/ J/ K/, Principles To Remember, Growing Leaders not just Leading Leaders,) Link to Chapter -02:

Content Curated By: Dr Shoury Kuttappa