How do we differentiate between needs and motives or motivations.? How not to be ruled by feelings, habits, impulses, and thoughts.?

Varieties of Motivation

One of the fundamental premises of the practice of Nonviolent Communication is that everything we do is an attempt to meet core human needs. Much can be said about what exactly counts as a need, and the difference between needs and the many strategies we employ in our attempts to meet them. There is no claim within this practice that we are all the same; only that we share the same core needs, and they serve as the only reason for us to do anything.

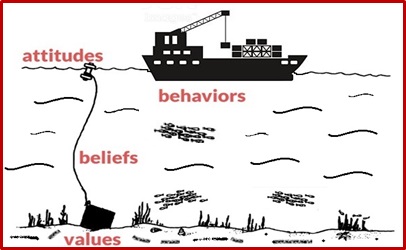

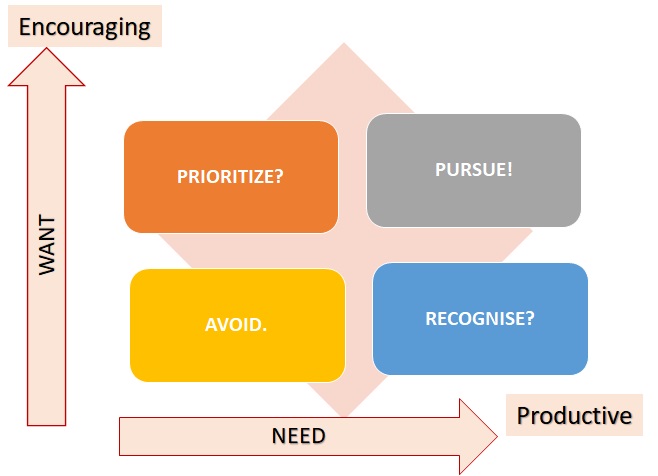

If everything is motivated by one or more human needs, then why are we even talking about varieties of motivations? It’s because what varies is the degree of awareness we bring to the relationship between our needs and our actions. Our various cultures don’t generally cultivate in us the practice of knowing what we want.

On the contrary, much of socialization is focused on questioning what we want and telling us any number of reasons for acting other than because we want something. This is a tragedy of enormous proportions, because what then happens is that what we want goes underground. We continue to act based on our needs without knowing what they are, and therefore with far less choice than we might otherwise do.

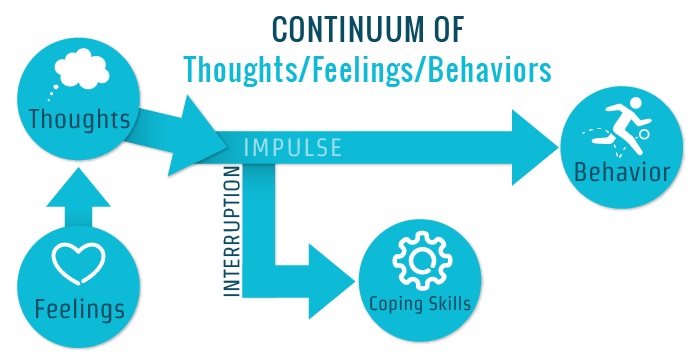

When we are not aware of needs, we act based on our feelings, thoughts, habits, or impulse. In essence, each of these types of motivation can serve as a way to deny our responsibility for our choices. Although each of these is connected with our needs, unless we specifically engage with the underlying needs, we are likely to continue to act with less choice than we can cultivate and achieve through becoming need-literate.

Feelings and Thoughts

Unless we develop some kind of practice of conscious engagement with our feelings, most of us experience them and respond to them as internal demands for action or avoidance of action whether or not it’s what we want. Fear, shame, or guilt may lead us to avoidance, while anger or excitement leads us to move toward an action.

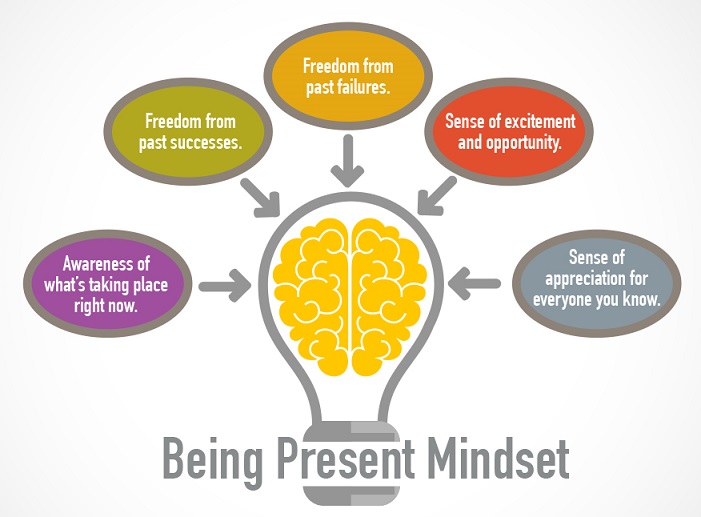

When we instantly translate feelings into actions, we sidestep any understanding of what we truly want. Because of the strength with which our feelings “command” action, we don’t have the opportunity to use feelings as what they are designed for, which is to be sources of information. Feelings serve a signal function. They arise from the constant stream of data about what is happening, and our ceaseless evaluation, under the radar of our awareness, as to whether or not our needs are met.

Listening to our feelings carefully allow us to trace them to the underlying needs that give rise to them. Choice lies in the capacity to understand, access, and embrace the underlying needs.

Thoughts mask our choice in a different way from how our feelings do. When we act based on what we should do, must do, or have to do, what we can’t do, what others will say, what is “rational and reasonable” or “appropriate,” we are linking our actions to something that is fundamentally external to us.

Feelings compel us from within, while thoughts compel us from without. The reason this is of such vital importance is that freedom is about choosing rather than being compelled. Choice is always internal: we may, and often will, take into consideration the effect of our actions and choices on others. Still, there is a world of difference between believing we have to do something and choosing it based on what’s important to us underneath the “have to.”

Indeed, our thoughts contain information about what is important to us, and in that way, they too are expressions of our needs. They usually lack the vibrancy of feelings, the sense of being alive, whether happily or not, in the experience of the feeling. They appear to be more “in control” and therefore give us a sense of being more at choice than when we act based on feelings.

The essence about connecting with ourselves at the level of needs rather than feelings or thoughts is that we then feel both the vibrancy of life that comes from being internally connected and the sense of clear choice that comes from knowing what’s important.

Habits

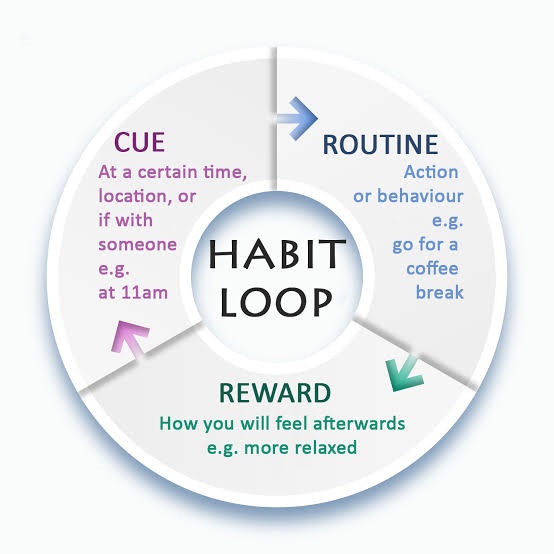

While feelings and thoughts give us the illusion of choice, habits are recognized by most of us as lacking choice. As a result, when people begin the practice of learning to connect with their needs, they easily fall into judging their habits (Self judgement).

Part of the difficulty with transforming habits into choice is that we often are not even aware of taking an action based on a habit. It’s only at other times, away from the action, that we may become aware that we acted based on a habit. Those are also the times we are most likely to judge ourselves for habitual behaviour. What makes it even more challenging is that finding the needs that give rise to the habit requires deep sleuthing/ reflections because the habits were formed in the past, when specific actions may have been powerful strategies to meet certain needs, and those very same strategies may no longer attend to those needs.

Habits, by their nature, are designed to relieve us from having to choose freshly each time, so it’s not likely to be easy to regain choice. This is where compassion for self is essential. It’s only when we have sufficient tenderness toward how hard changing habits can be that we can create a different motivation for the process of change itself: instead of being motivated by “should” thinking, we can find the needs that lead us to want to engage with the habit.

Freedom and authenticity are often powerful motivators. Embracing all our needs in relation to our habits may shift the emotional quality of trying to make a change, for example, from urgency to calm resolve. This grounding can help us mourn any unmet needs that the habits lead to, envision other strategies to meet as many needs as we can, and develop clear requests of ourselves to support the desired change.

It is critical to reach full connection with the needs that lead us to choose the habitual behaviour. This connection is essential for making change that is grounded in self-compassion. Without this quality, we cannot have sufficient internal cooperation, and the attempt to change is likely to be a self-demand that will recreate internal resistance to the change.

Impulse and Intuition

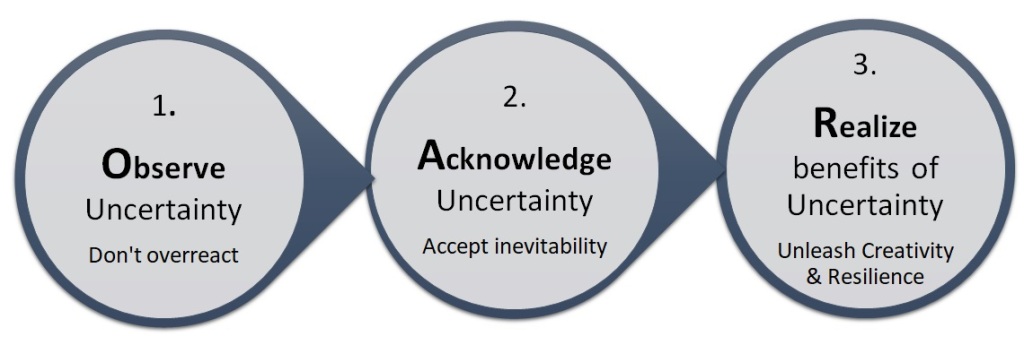

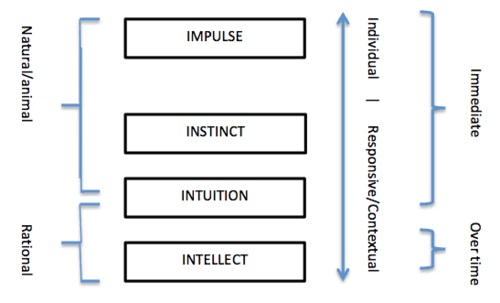

The final contender for being a primary motivator is impulse. Like habits, impulses are recognized as lacking choice and are therefore judged. Contrary to habits, though, impulses appear as “natural” and full of life. Sometimes, especially when we have been enslaved by habits and painful thought patterns, responding to our impulses and acting on them can seem like a welcome relief. They can give us the illusion of coming back to ourselves.

Clearly, impulses are completely spontaneous, and yet they may not necessarily be related to what we truly want. Our impulses can arise for so many reasons, and by themselves, we have no clear way to assess their capacity to realise needs.

Intuition seems to come from a different internal place, and doesn’t have the force of an impulse. An impulse, like a feeling, has a quality of propelling us to action. Intuition’s voice is soft and requires careful attention to discern what is being said. Some of us honor and cherish our intuition, recognizing it as a source of wisdom, directing access to what we want without the painstaking effort of discerning what our needs are.

**Source Credits: a) The book- Thinking, Fast and Slow by Daniel Kahneman . . . . . . . . . . b) The book- Nudge by -Richard H. Thaler & Cass R. Sunstein . . . . . . . . . . . .c) The book- Predictably Irrational-by Dan Ariely . . . . . . . . . d) The book- Atomic Habitsby James Clear

Curated By: Dr Shoury Kuttappa