“The most difficult subjects can be explained to the most slow-witted man if he has not formed any idea of them already; but the simplest thing cannot be made clear to the most intelligent man if he is firmly persuaded that he knows already, without a shadow of doubt, what is laid before him.”- Leo Tolstoy.

Why don’t facts change our minds? And why would someone continue to believe a false or inaccurate idea anyway? How do such behaviors serve us?

The Logic of False Beliefs

Humans need a reasonably accurate view of the world in order to survive. If our model of reality is wildly different from the actual world, then we struggle to take effective actions each day. However, truth and accuracy are not the only things that matter to the human mind. Humans also seem to have a deep desire to belong.

“Humans are herd animals. We want to fit in, to bond with others, and to earn the respect and approval of our peers. Such inclinations are essential to our survival. For most of our evolutionary history, our ancestors lived in tribes. Becoming separated from the tribe—or worse, being cast out—was a death sentence.”- James Clear – Atomic Habits

Understanding the truth of a situation is important, but so is remaining part of a tribe. While these two desires often work well together, they occasionally come into conflict. In many circumstances; social connection is actually more helpful to our daily life than understanding the truth of a particular fact or idea. People are embraced or condemned according to their beliefs, so one function of the mind may be to hold beliefs that bring the belief-holder the greatest number of allies, protectors, or disciples, rather than beliefs that are most likely to be true.

We don’t always believe things because they are correct. Sometimes we believe things because they make us look good to the people we care about.If a brain anticipates that it will be rewarded for adopting a particular belief, it’s perfectly happy to do so, and doesn’t much care where the reward comes from. False beliefs can be useful in a social sense even if they are not useful in a factual sense. For lack of a better phrase, we might call this approach “factually false, but socially accurate.” When we have to choose between the two, people often select friends and family over facts.

This insight not only explains why we might hold our tongue at a dinner party or look the other way when our parents say something offensive, but also reveals a better way to change the minds of others.

Facts Don’t Change Our Minds. Friendship Does.

Convincing someone to change their mind is really the process of convincing them to change their tribe. If they abandon their beliefs, they run the risk of losing social ties. We can’t expect someone to change their mind if we take away their community too. We have to give them somewhere to go. Nobody wants their worldview torn apart if loneliness is the outcome.The way to change people’s minds is to become friends with them, to integrate them into our tribe, to bring them into our circle. Now, they can change their beliefs without the risk of being abandoned socially.

The British philosopher Alain de Botton suggests that we simply share meals with those who disagree with us. Sitting down at a table with a group of strangers has the incomparable and odd benefit of making it a little more difficult to hate them with impunity. Prejudice and ethnic strife feed off abstraction. However, the proximity required by a meal – something about handing dishes around, unfurling napkins at the same moment, even asking a stranger to pass the salt – disrupts our ability to cling to the belief that the outsiders who wear unusual clothes and speak in distinctive accents deserve to be sent home or assaulted. Perhaps it is not difference, but distance that breeds tribalism and hostility. As proximity increases, so does understanding. Facts don’t change our minds. Friendship does.

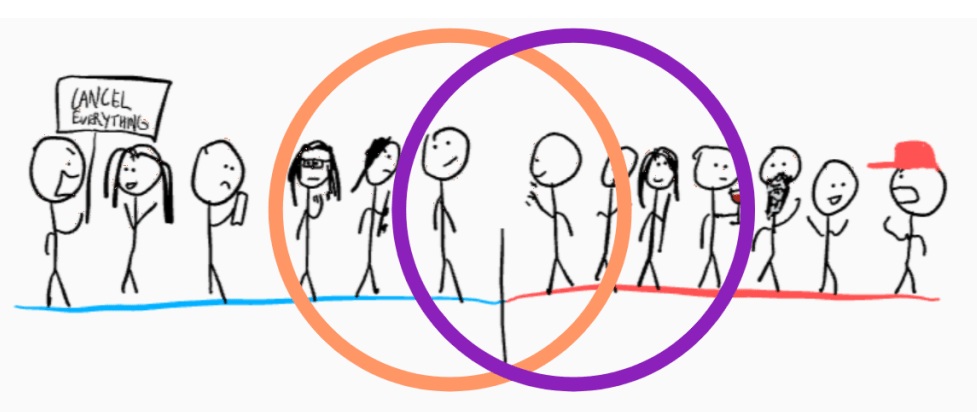

The Spectrum of Beliefs

The people who are most likely to change our minds are the ones we agree with on 98 percent of topics. If someone we know, like, and trust believes a radical idea, we are more likely to give it merit, weight, or consideration. But if someone wildly different than us proposes the same radical idea, well, it’s easy to dismiss them as a crackpot.

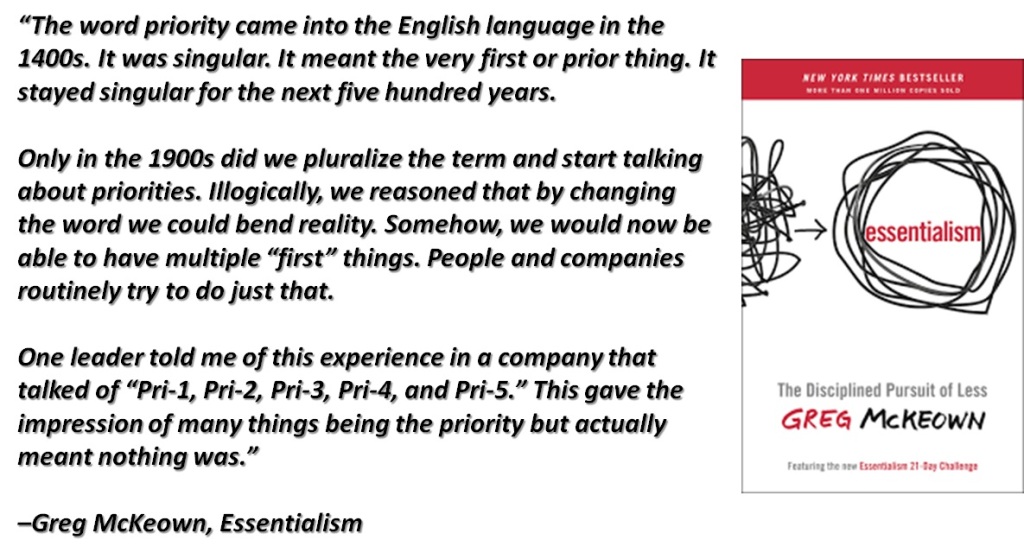

One way to visualize this distinction is by mapping beliefs on a spectrum. If we divide this spectrum into 10 units and we find ourselves at Position 7, then there is little sense in trying to convince someone at Position 1. The gap is too wide. When we are at Position 7, our time is better spent connecting with people who are at Positions 6 and 8, gradually pulling them in our direction.

The most heated arguments often occur between people on opposite ends of the spectrum, but the most frequent learning occurs from people who are nearby. The closer we are to someone, the more likely it becomes that the one or two beliefs we don’t share will bleed over into our own mind and shape our thinking. The further away an idea is from our current position, the more likely we are to reject it outright.When it comes to changing people’s minds, it is very difficult to jump from one side to another. We can’t jump down the spectrum – we have to slide down it.

Any idea that is sufficiently different from our current worldview will feel threatening. And the best place to ponder a threatening idea is in a non-threatening environment. As a result, books are often a better vehicle for transforming beliefs than conversations or debates. In conversation; people have to carefully consider their status and appearance. They want to save face and avoid looking stupid. When confronted with an uncomfortable set of facts, the tendency is often to double down on their current position rather than publicly admit to being wrong. Books resolve this tension. With a book, the conversation takes place inside someone’s head and without the risk of being judged by others. It’s easier to be open-minded when you aren’t feeling defensive.

Arguments are like a full-frontal attack on a person’s identity. Reading a book (or a text/email/letter) is like slipping the seed of an idea into a person’s brain and letting it grow on their own terms. There is enough wrestling going on in someone’s head when they are overcoming a pre-existing belief. They don’t need to wrestle with you too.

Why False Ideas Persist

There is another reason bad ideas continue to live on, which is that people continue to talk about them. Silence is death for any idea. An idea that is never spoken or written down dies with the person who conceived it. Ideas can only be remembered when they are repeated. They can only be believed when they are repeated.

People also repeat bad ideas when they complain about them. Before we can criticize an idea, we have to reference that idea. We end up repeating the ideas we are hoping people will forget—but, of course, people cannot forget them because we keep talking about them. The more we repeat a bad idea, the more likely people are to believe it.

Each time we attack a bad idea, we are feeding the very monster we are trying to destroy. Our time is better spent championing good ideas than tearing down bad ones. The best thing that can happen to a bad idea is that it is forgotten. The best thing that can happen to a good idea is that it is shared.

What Is The Goal?

There are instances when it is useful to point out an error or criticize a bad idea. But we have to ask ourselves, “What is the goal?” Presumably, we want to criticize bad ideas because we think the world would be better off if fewer people believed them. In other words, we think the world would improve if people changed their minds on a few important topics.If the goal is to actually change minds, then, criticizing the other side may not be the best approach.

Most people argue to win, not to learn. People often act like soldiers rather than scouts. Soldiers are on the intellectual attack, looking to defeat the people who differ from them. Victory is the operative emotion. Scouts, meanwhile, are like intellectual explorers, slowly trying to map the terrain with others. Curiosity is the driving force. If we want people to adopt our beliefs, we need to act more like a scout and less like a soldier. Are we willing to not win in order to keep the conversation going?

Be Kind First, Be Right Later

“Always remember that to argue, and win, is to break down the reality of the person you are arguing against. It is painful to lose your reality, so be kind, even if you are right.”- Haruki Murakami

When we are in the moment, we can easily forget that the goal is to connect with the other side, collaborate with them, befriend them, and integrate them into our tribe. We are so caught up in winning that we forget about connecting. It is easy to spend our energy labelling people rather than working with them.The word “kind” originated from the word “kin.” When you are kind to someone it means you are treating them like family. Develop a friendship. Share a meal. Be Kind.

**Source Credits: 1) Language, Cognition, and Human Nature: Selected Articles by Steven Pinker. 2) Religion for Atheists by Alain de Botton. 3) “Why you think you’re right — even if you’re wrong” by Julia Galef.

Content Curated By: Dr Shoury Kuttappa.