The term the “curse of knowledge” was coined in a 1989 paper by researchers Colin Camerer, George Loewenstein, and Martin Weber. This phenomenon is sometimes also conceptualized as epistemic egocentrism, though some theoretical distinctions may be drawn between these concepts.

The curse of knowledge is a cognitive bias that causes people to fail to properly understand the perspective of those who do not have as much information as them. For example, the curse of knowledge can mean that an expert in some field might struggle to teach beginners, because the expert intuitively assumes that things that are obvious to them are also obvious to the beginners, even though that’s not the case. Because the curse of knowledge can cause issues in various areas of life, such as when it comes to communicating with others, it’s important to understand it.

The Curse Of Knowledge: Common Occurrences & Influences

This can make it harder for experts to teach beginners (also known as the curse of expertise). For example, a math professor might find it difficult to teach first-year math students, because it’s hard for the professor to account for the fact that they know much more about the topic than the students.

This can make it harder for people to communicate. For example, it can be difficult for a scientist to discuss their work with laypeople, because the scientist might struggle to remember that those people aren’t familiar with the terminology in the scientist’s field.

This can make it harder for people to predict the behavior of others. For example, an experienced driver may be surprised by something dangerous that a new driver does, because the experienced driver struggles to understand that the new driver doesn’t understand the danger of what they’re doing. This aspect of the curse of knowledge is associated with people’s expectation that those who are less-informed than them will use information that the less-informed individuals don’t actually have.

This can make it harder for people to understand their own past behavior. For example, it can cause someone to think that they were foolish for making a certain decision in the past, even though the information that they had at the time actually strongly supported that decision. This aspect of the curse of knowledge can manifest in various ways and be referred to using various terms, such as the hindsight bias, knew-it-all along effect, and creeping determinism.

When it comes to the curse of knowledge, the perspective of the less-informed individual, whether it’s a different person or one’s past self, is often referred to as a naive perspective.

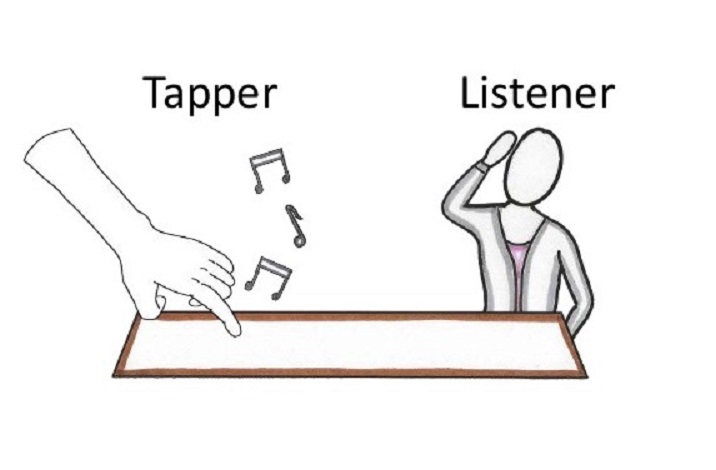

The Tapping Study

One well-known example of the curse of knowledge is the tapping study. In this study, participants were randomly assigned to be either a tapper or a listener. Each tapper finger-tapped three tunes (which were selected from a list of 25 well-known songs) on a desk, and was then asked to estimate the probability that the listener will be able to successfully identify the song that they tapped, based only on the finger tapping.

On average, tappers estimated that listeners will be able to correctly identify the tunes that they tapped in about 50% of cases, with estimates ranging anywhere from 10% to 95%. However, in reality, listeners were able to successfully identify the tune based on the finger tapping in only 2.5% of cases, which is far below even the most pessimistic estimate provided by a tapper, and which therefore represents evidence of the curse of knowledge.

Overall, the tapping study demonstrates how the curse of knowledge can affect people’s judgment. Specifically, it shows that people who know which tune is being tapped have an easy time identifying it, and therefore struggle to accurately predict the perspective of others, who don’t have the same knowledge that they do.

The Psychology & Causes Of The Curse Of Knowledge

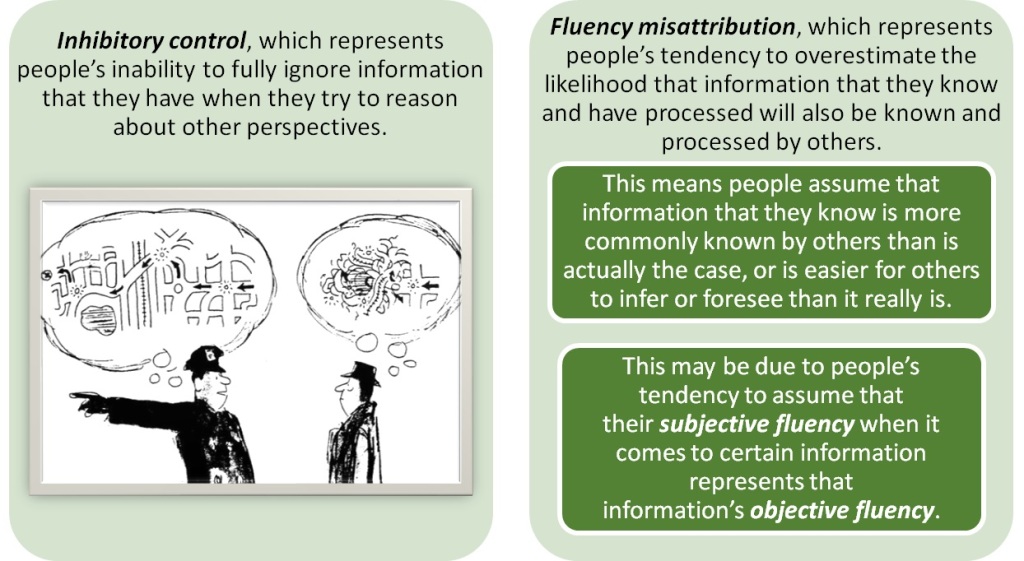

The curse of knowledge is attributed to two main cognitive mechanisms:

People’s curse of knowledge can be caused by either of these mechanisms, and both mechanisms may play a role at the same time. Other cognitive mechanisms may also lead to the curse of knowledge. For example, one such mechanism is anchoring and adjustment, which in this case means that when people try to reason about a less-informed perspective, their starting point is often their own perspective, which they struggle to adjust from properly.

All these mechanisms, in turn, can be attributed to various causes, such as the brain’s focus on acquiring and using information, rather than on inhibiting it, which is beneficial in most cases but problematic in others. In addition, various factors, such as age and cultural background, can influence people’s tendency to display the curse of knowledge, as well as the way and degree to which they display it.

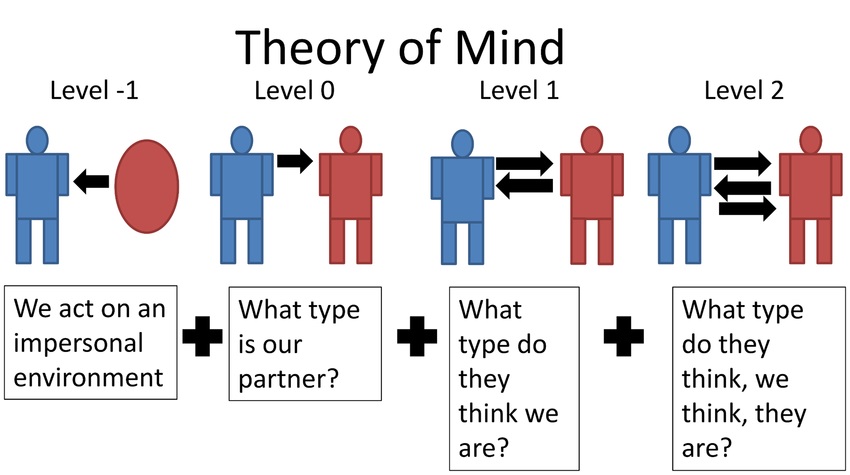

Finally, other psychological concepts are associated with the curse of knowledge. The most notable of these is theory of mind, which is the ability to understand that other people have perceptions, thoughts, emotions, beliefs, desires, and intentions that are different from our own, and that these things can influence people’s behavior. Insufficient theory of mind can therefore lead to an increase in the curse of knowledge, and conversely, proper theory of mind can reduce the curse of knowledge.

Dealing with The Curse Of Knowledge

There are several things that you can do to reduce the curse of knowledge:

Other Debiasing Techniques

We can use various general debiasing techniques, such as slowing down our reasoning process and improving our decision-making environment. In addition, we can use debiasing techniques that are meant to reduce egocentric biases, such as visualizing the perspective of others and then adjusting our judgment based on this, or using self-distancing language (e.g., by asking “are you teaching in a way that the students can understand?” instead of “am I teaching in a way that the students can understand?”).

It is important to keep in mind that none of these techniques may work perfectly in every situation. This means, for example, that some techniques might not work for some individuals in some circumstances, or that even if a certain technique does work, it will only reduce someone’s curse of knowledge to some degree, but won’t eliminate it entirely.

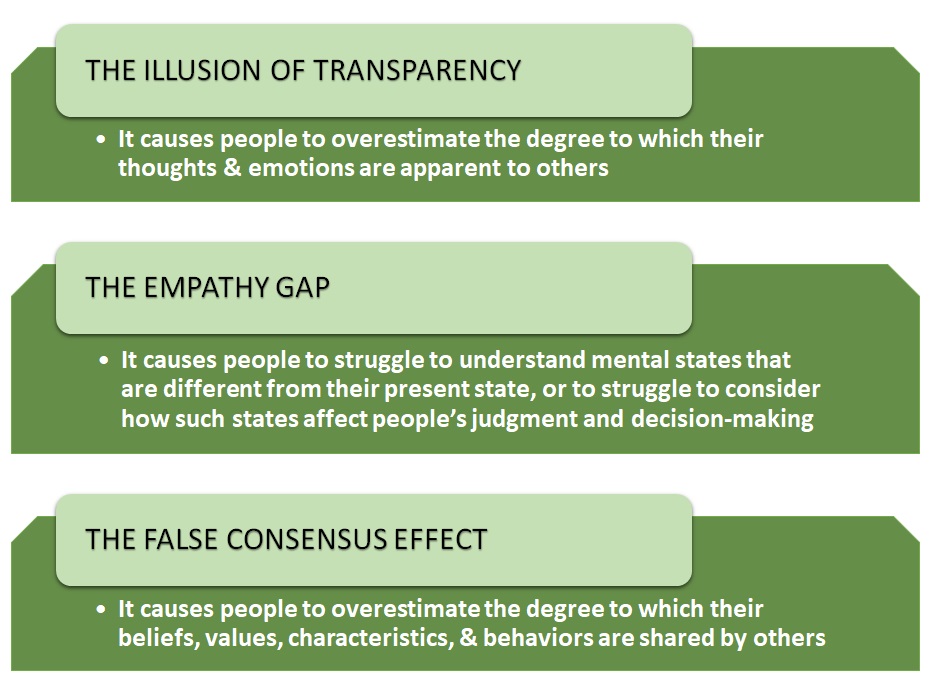

Related Biases

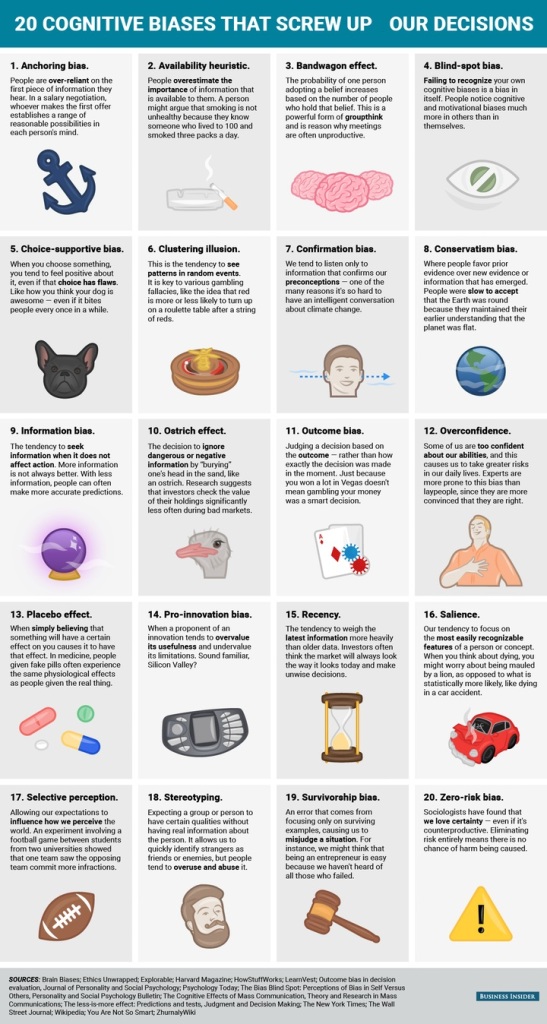

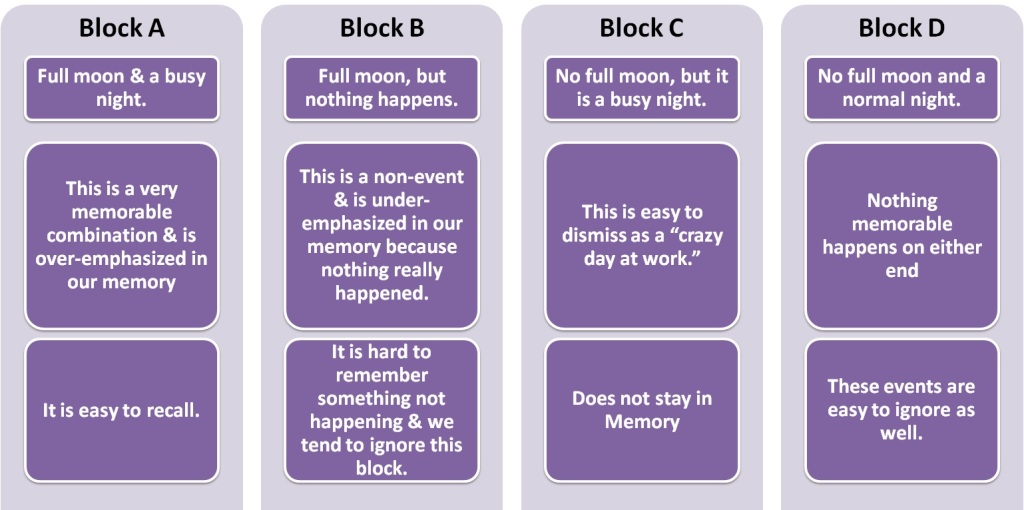

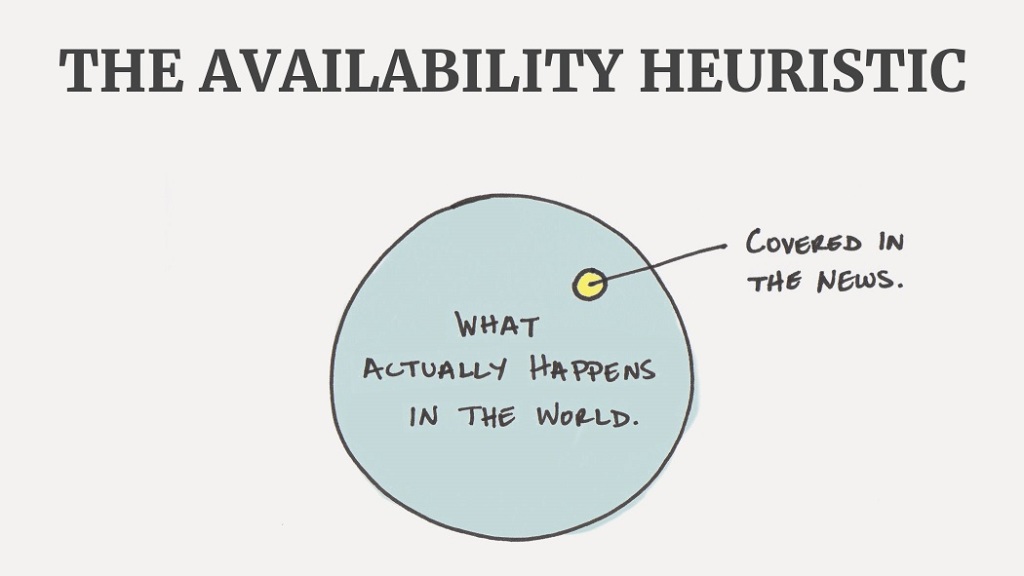

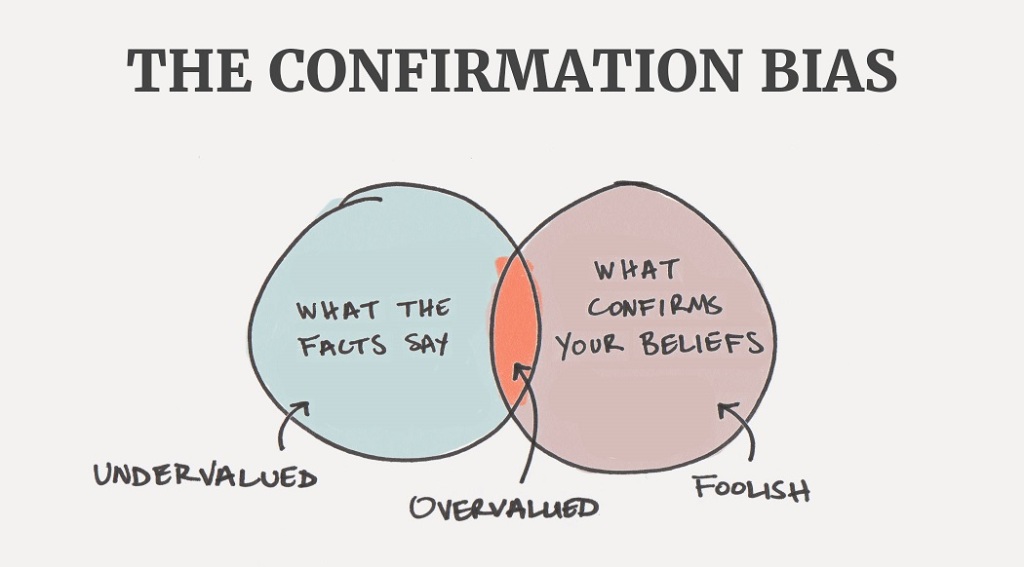

The curse of knowledge is considered to be a type of egocentric bias, since it causes people to rely too heavily on their own point of view when they try to see things from other people’s perspective. However, an important feature of the curse of knowledge, which differentiates it from some other egocentric biases, is that it is asymmetric, in the sense that it influences those who attempt to understand a less-informed perspective, but not those who attempt to understand a more-informed perspective. The curse of knowledge is also associated with various other cognitive biases, such as:

***Source Credits:-

http://www.effectiviology.com/

Content Curated By: Dr Shoury Kuttappa