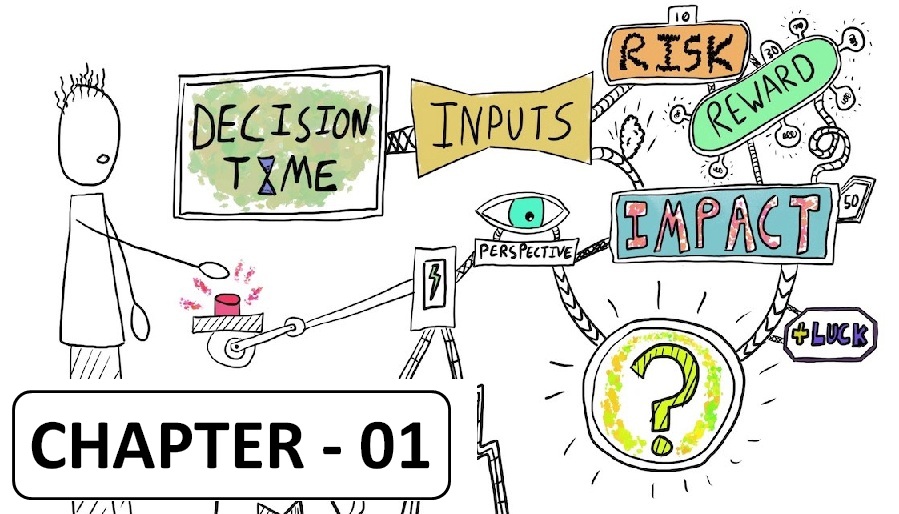

Decision making is a cognitive process leading to the selection of a course of action among alternatives. It is a method of reasoning which can be rational or irrational, and can be based on explicit assumptions or tacit assumptions. Common examples include shopping, deciding what to eat, when to sleep, and deciding whom or what to vote for in an election.

Decision making is said to be a psychological construct. This means that although we can never “see” a decision, we can infer from observable behaviour that a decision has been made. It is a construction that imputes commitment to action.

Structured rational decision making is an important part of all science-based professions. For example, medical decision making often involves making a diagnosis and selecting an appropriate treatment. Some research using naturalistic methods shows, however, that in situations with higher time pressure, higher stakes, or increased ambiguities, experts use intuitive decision making rather than structured approaches, following a recognition primed decision approach to fit a set of indicators into the expert’s experience and immediately arrive at a satisfactory course of action without weighing alternatives.

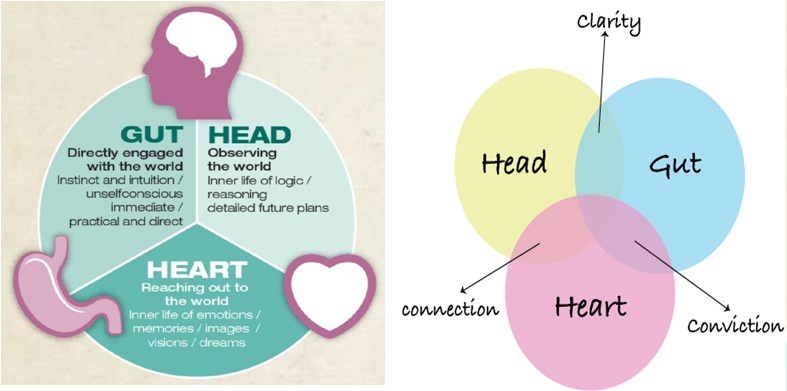

Head, Heart and Gut – Powerful Decision Makers

We are living in unprecedented times of stress, confusion, and overwhelm. We all need resources to help navigate these challenging times and make the right decisions for the highest and best long-term good for ourselves, our families and our businesses. Those resources can be found within each of us if we pause to consider three reliable indicators: the head (intellect), the heart (feelings), and the gut (intuition).

Head: Makes use of intellect and past knowledge. This involves using the conscious mind to discern questions that need to be answered. For example, is this person telling the truth? What has worked in the past? Have we done our due diligence and homework before making a decision?

Heart: The internal part of us, the voice inside, tells us when things feel right or wrong. For example, are we relaxed around the person we are asking the question about, or do we feel upright and uncomfortable? Keep in mind that our bodies do talk to us.

Gut: We need to trust our intuition. If it doesn’t feel right, chances are it’s not right for us. What may be right for one person can be wrong for another. Our gut instinct, our inner voice, is always there for us when we take the time to pay attention and listen.

Decision making styles

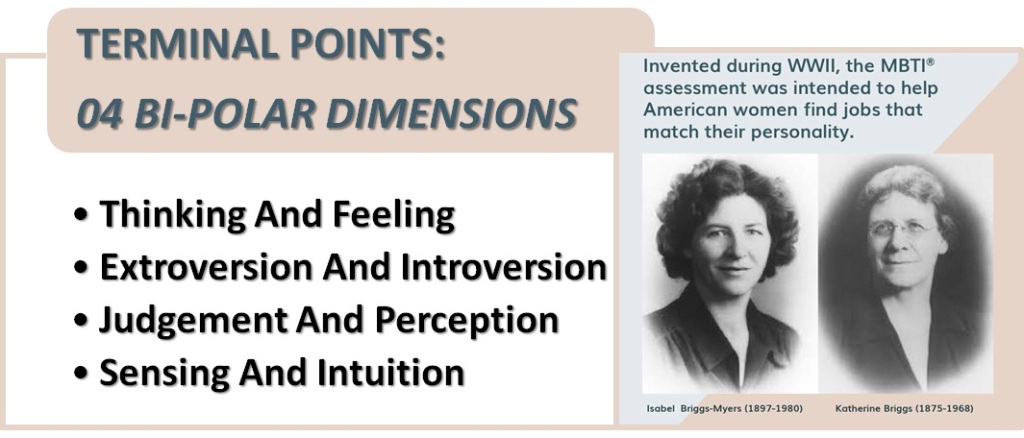

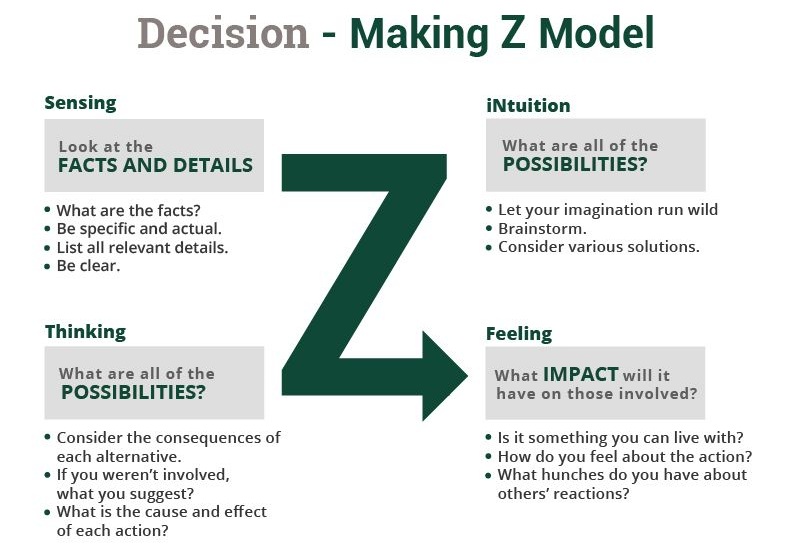

A person’s decision making process depends to a significant degree on their cognitive style. There are more than a few models to explain these styles. For example, the common personality test Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI) examines a set of four bi-polar dimensions, which are:

She claimed that a person’s decision making style is based largely on how they score on these four dimensions. For example, someone that scored near the thinking, extroversion, sensing, and judgement ends of the dimensions would tend to have a logical, analytical, objective, critical and empirical decision making style.

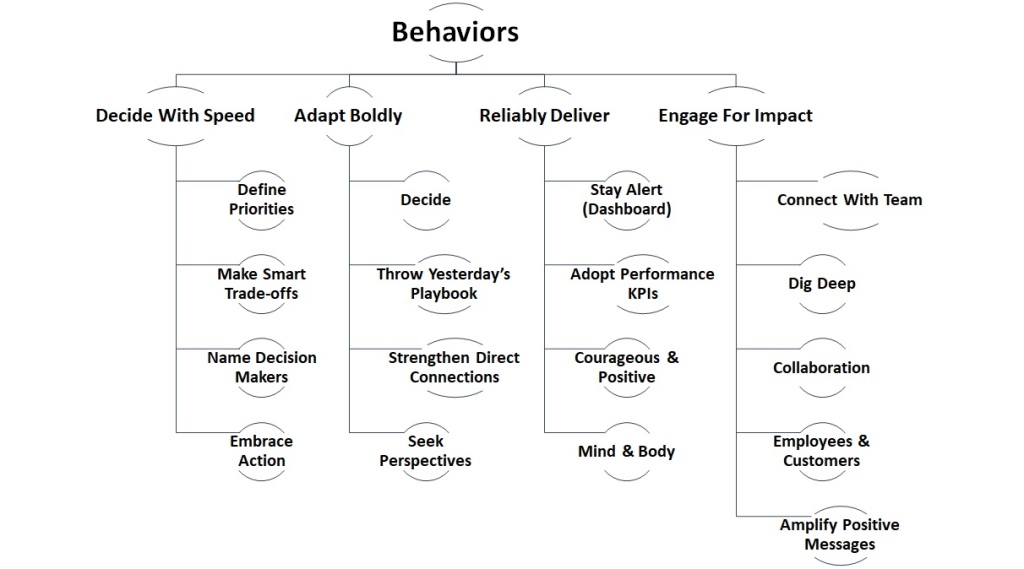

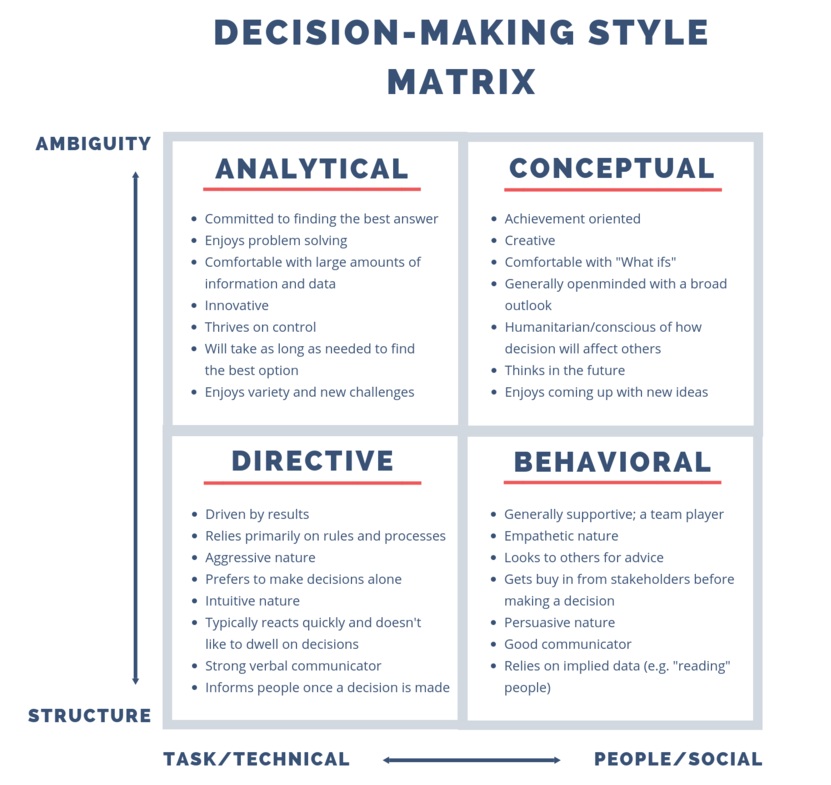

Every leader prefers a different way to contemplate a decision. The four styles of decision making are directive, analytical, conceptual and behavioral. Each style is a different method of weighing alternatives and examining solutions.

The two spectrum work together to create the decision-making style framework. The first spectrum is structure vs. ambiguity. This spectrum measures people’s propensity to prefer either structure (i.e., defined processes and expectations) or ambiguity (i.e., open-ended and flexible). The second spectrum is task/technical vs. people/social. This spectrum measures if the motivation to make a specific choice is guided more by a desire to be right, or to get results (task/technical), or if it’s to create harmony or social impact (people/social).

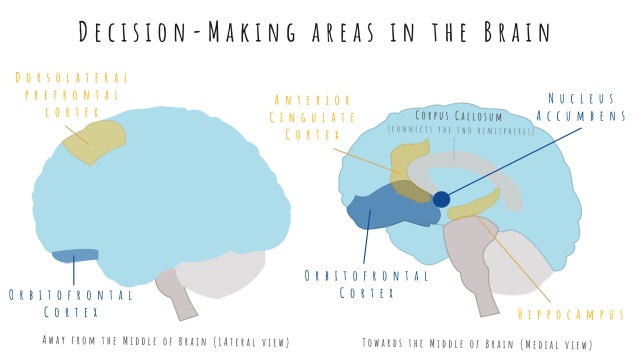

Areas Of The Brain (Neuroscience) In Decision Making

Decision Making In Uncertainty

Decision making often occurs in the face of uncertainty about whether one’s choices will lead to benefit or harm. Emotion appears to aid the decision-making process heavily in the face of uncertainty. The somatic-marker hypothesis is a neuro-biological theory of how decisions are made in the face of uncertain outcome. In brief, this theory holds that such decisions are aided by emotions, in the form of bodily states, that are elicited during the deliberation of future consequences and that mark different options for behavior as being advantageous or disadvantageous. This process involves an interplay between neural systems that elicit emotional/bodily states and neural systems that map these emotional/bodily states.

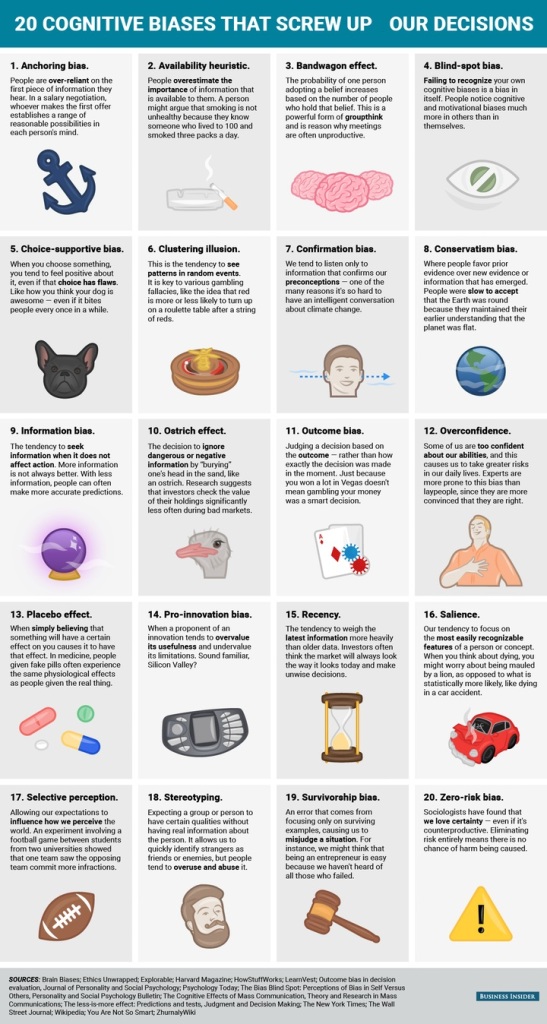

Cognitive and personal biases in decision making

It is generally agreed that biases can creep into our decision making processes, calling into question the correctness of a decision. Some of the more commonly debated cognitive biases may be:

***To be continued in Chapter 02 (Various Techniques in use in individual and group Decision Making) Link to Chapter -02:

Content Curated By: Dr Shoury Kuttappa