***Continued from Chapter 01 (Covered previously: What is Situational Ethics, The Meaning & Context of Agape, The Three Views Of Situational Ethics)

Link to Chapter 01:

The Four Working Principles of Situationism

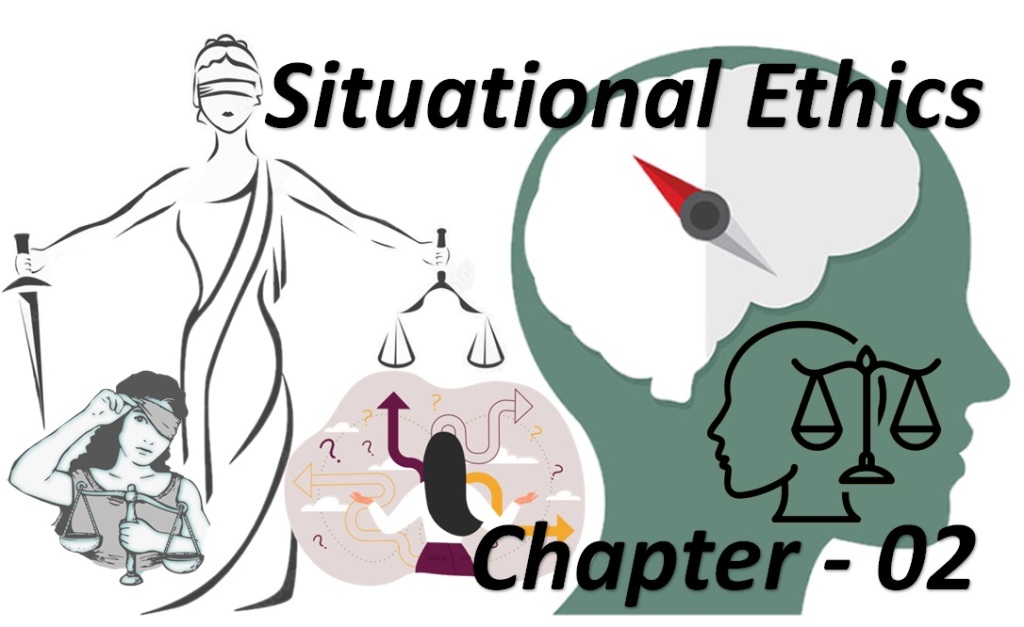

Principle 1. Pragmatism

The situationalist follows a strategy, which is pragmatic. “Pragmatism” is a well worked-out philosophical position adopted by the likes of John Dewey (1859–1952), Charles Peirce (1839–1914) and William James (1842–1910). Fletcher does not want his theory associated with these views and rejects all the implications of this type of “Pragmatism”.

What makes his view pragmatic is very simple. It is just his attraction to moral views, which do not try to work out what to do in the abstract, but rather explores how moral views might play out in each real life situations.

Principle 2: Relativism

Even with his rejection of Antinomianism and his acceptance of one supreme principle of morality, Fletcher, surprisingly, still calls himself a relativist. It is just an appeal for people to stop trying to “lay down the law” for all people in all contexts. If situations vary then consequences vary and what we ought to do will change accordingly. This is a very simple, unsophisticated idea and just means that what is right or wrong is related to the situation we are in.

Principle 3: Positivism

His use of “positivism” is not the philosophical idea with the same name but rather is where any moral or value judgment in ethics, like a theologian’s faith propositions, is a decision — not a conclusion. It is a choice, not a result reached by force of logic or reasoning, rather it is a decision we take.

Principle 4: Personalism

Love is something that is experienced by people. So Personalism is the view that if we are to maximize love we need to consider the person in a situation — the “who” of a situation.

Conscience as a Verb not a Noun

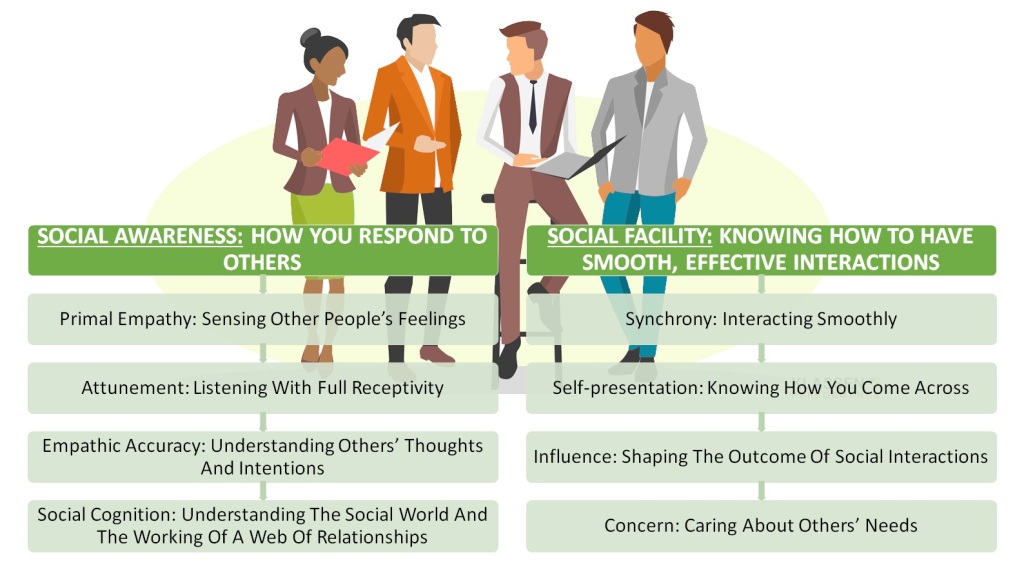

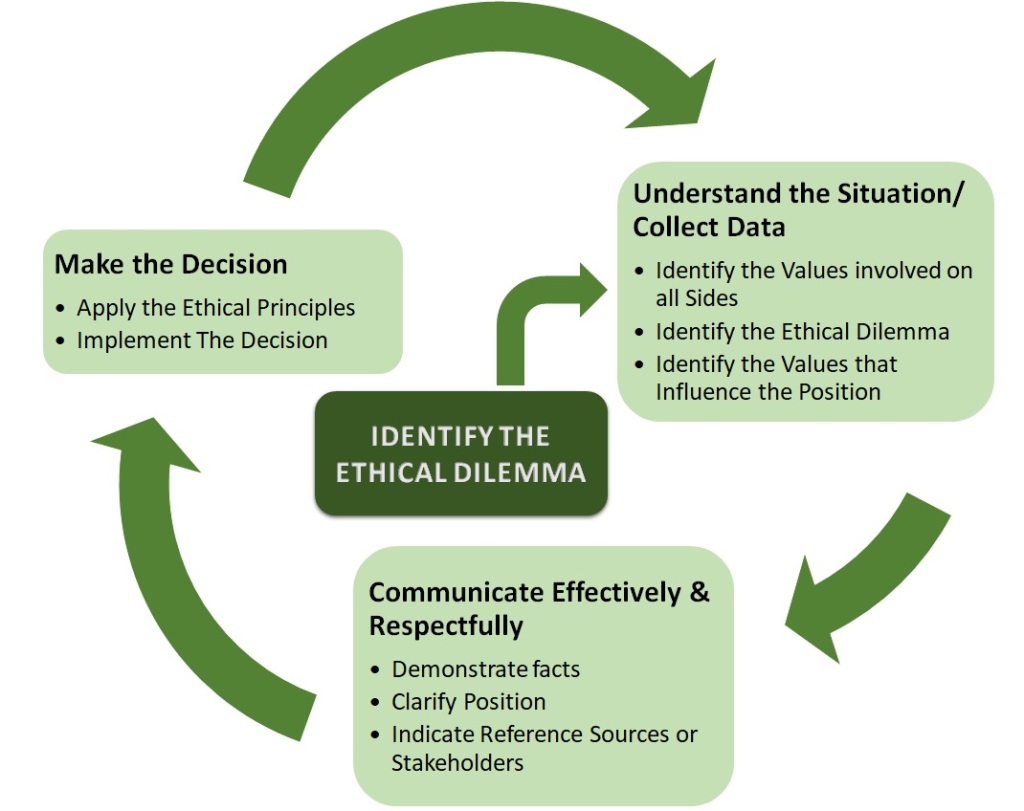

“Conscience” plays a role in working out what to do. Conscience is not the name of an internal faculty nor is it a sort of internal “moral compass”.

Fletcher refers to conscience as a verb. Imagine we have heard some bullies laughing because they have sent our friend some offensive texts and we are trying to decide whether or not to check his phone to delete the texts before he does. The old “noun” view of conscience would get us to think about this in the abstract, perhaps reason about it.

Instead, we need to be in the situation, and experience the situation, we need to be doing (hence “verb”) the experiencing. Maybe, we might conclude that it is right to go into our friend’s phone, maybe we will not but whatever happens the outcome could not have been known beforehand. What our conscience would have us do is revealed when we live in the world and not through armchair reflection.

The Six Propositions of Situation Ethics

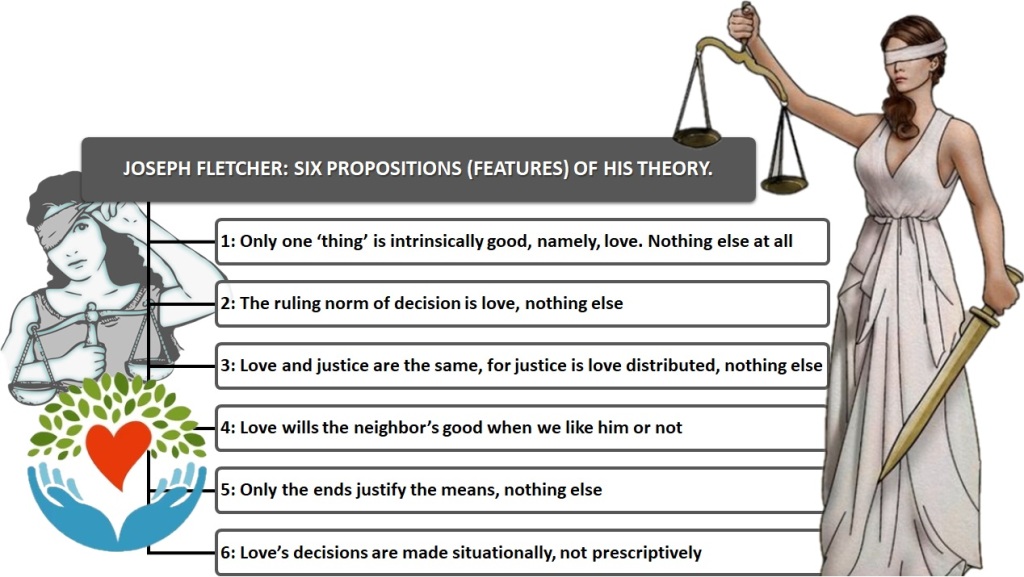

1: Only one ‘thing’ is intrinsically good; namely, love, nothing else at all

There is one thing which is intrinsically good, that is good irrespective of context, namely love. If love is what is good, then an action is right or wrong in as far as it brings about the most amount of love.

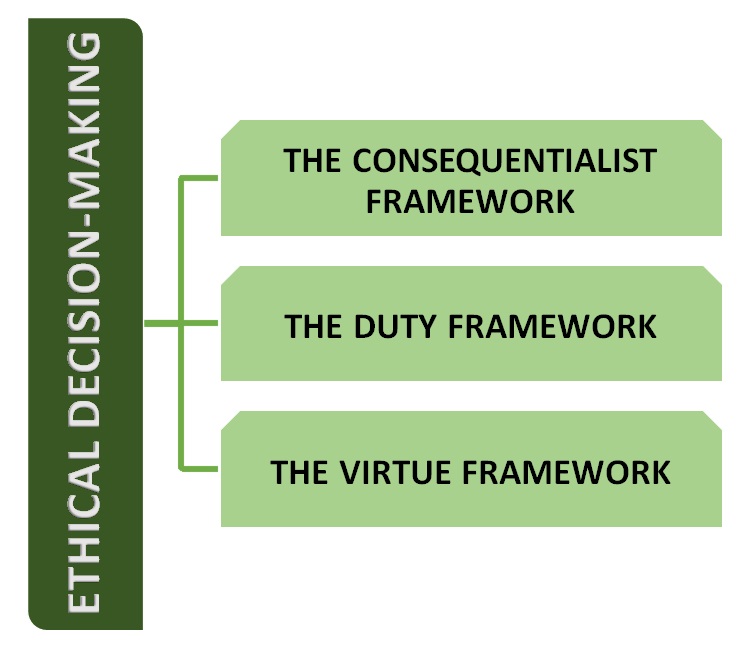

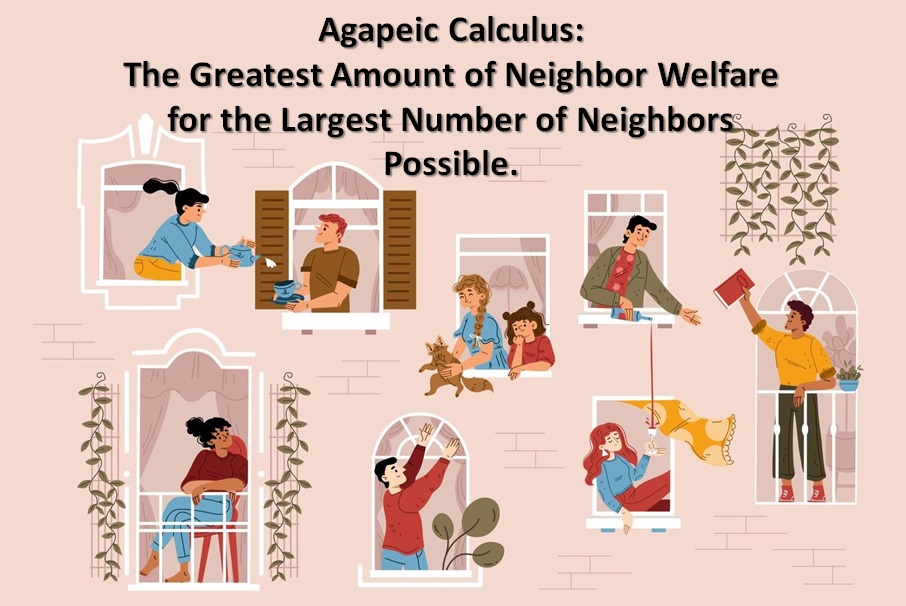

Agapeic Calculus is a moral framework rooted in the pursuit of maximizing neighbor welfare for the greatest number of individuals within a community. Unlike conventional notions of love centered on emotional attachment or desire, this concept emphasizes the broader notion of concern for the well-being of others. In this context, “welfare” encompasses not only material prosperity but also factors such as health, happiness, and overall quality of life. By prioritizing the collective welfare of the community over individual interests, Agapeic Calculus seeks to foster a society characterized by compassion, empathy, and a commitment to the common good. In essence, it advocates for a calculus of altruism and ethical decision-making that aims to uplift and support as many neighbors as possible, thereby cultivating a more just and harmonious social order.

2: The ruling norm of decision is love, nothing else

Given our modern context and how people typically talk of “love” it is probably unhelpful to even call it “love”. For instance, we will all recall the following news item. In February 1993, Mrs Johnson’s son, Laramiun Byrd, 20, was shot in the head by 16-year-old Oshea Israel after an argument at a party in Minneapolis, Minnesota. Mrs Johnson subsequently forgave her son’s killer and after he had served a 17-year sentence for the crime, asked him to move in next door to her. She was not condoning his actions, nor will she ever forget the horror of those actions, but she does love her son’s killer. That love is agápē.

Reference:

3: Love and justice are the same, for justice is love distributed, nothing else

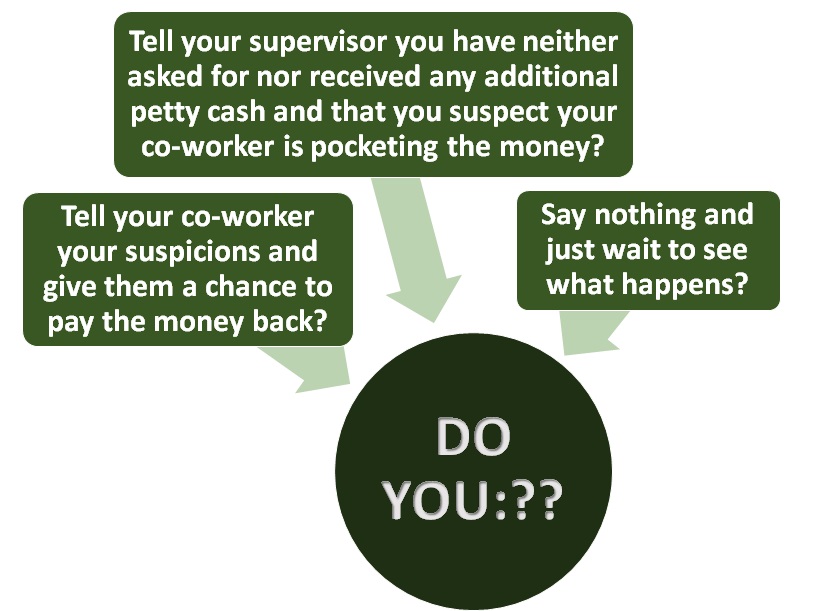

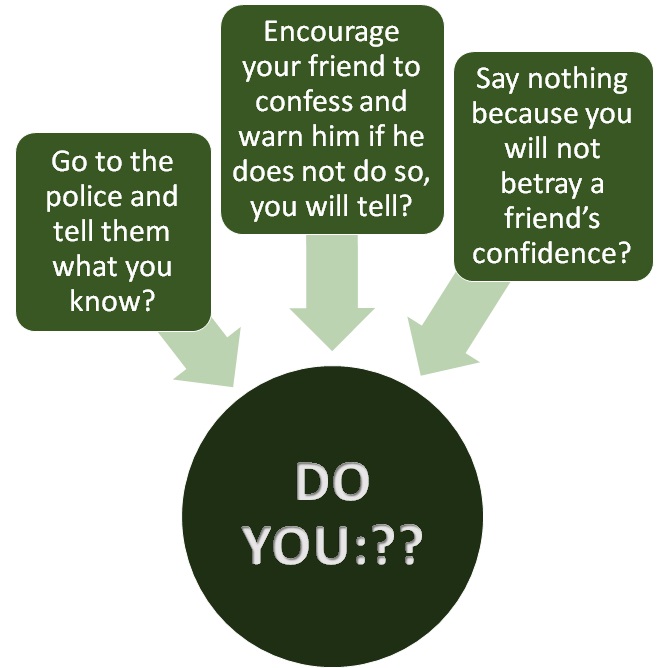

Practically all moral problems we encounter can be boiled down to an apparent tension between “justice” on the one hand and “love” on the other. Consider a recent story:

This could be expressed as a supposed tension between “love” of family and doing the right thing — “justice”. Imagine we are trying to decide what is the best way to distribute food given to a charity, or how a triage nurse might work in a war zone. In these cases we might put the problem like this. We want to distribute fairly, but how should we do this? To act justly or fairly is precisely to act in love. “Love is justice, justice is love”.

4: Love wills the neighbor’s good when we like him or not

Agápē is in the business of loving the unlovable. So related to our enemies. Love does not ask us to lose or abandon our sense of good and evil, or even of superior and inferior; it simply insists that however we rate them, and whether we like them nor not, they are our neighbors and are to be loved.

5: Only the ends justify the means, nothing else

Any action we take, if considered as an action independent of its consequences, is literally “meaningless and pointless”. An action, such as telling the truth, only acquires its status as a means by virtue of an end beyond itself.

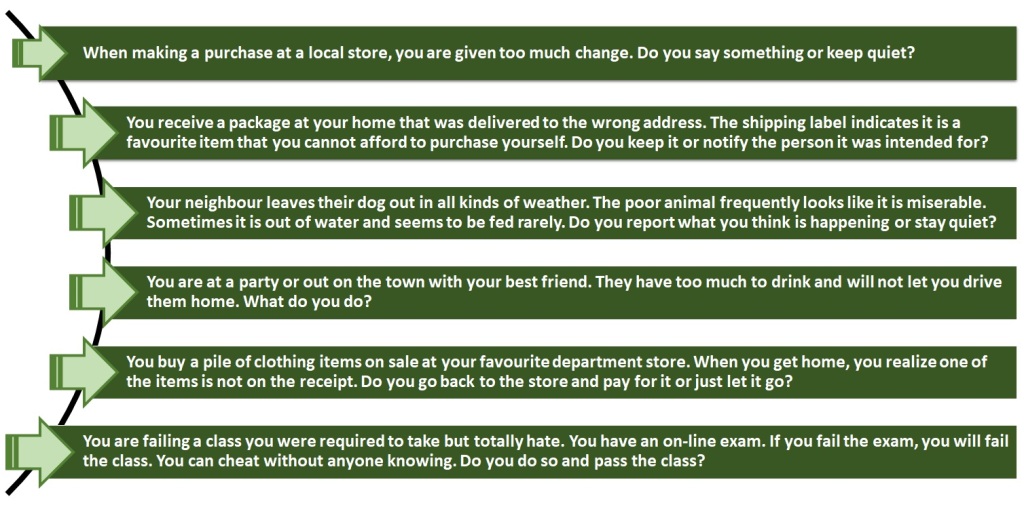

6: Love’s decisions are made situationally, not prescriptively

Ethical decisions exist in a grey area most of the time. No decision can be taken before considering the situation. Consider the example of a woman in Arizona who learned that she might “bear a defective baby because she had taken thalidomide”. What should she do? The loving decision was not one given by the law, which stated that all abortions are wrong. However, she travelled to Sweden where she had an abortion. Even if the embryo had not been defective according to Fletcher her actions were “brave and responsible and right” because she was acting in light of the particulars of the situation to bring about the most love.

The Criticism of Situational Ethics

John Robinson, an Anglican Bishop of Woolwich and Trinity College started as a firm supporter of situational ethics referring to the responsibility it gave the individual in deciding the morality of their actions. However, he later withdrew his support for the theory recognizing that people could not take this sort of responsibility, remarking that “It will all descend into moral chaos.”

The central focus on agape as the moral guide for behavior allows to claim that an action might be right in one context, but wrong in a different context — depending on the level of agape brought about. Despite how popular the theory was it is not philosophically sophisticated, and we soon run into problems in trying to understand it.

Another problem with teleological or consequential theories is that they are based on the future consequences, and the future is quite hard to predict in some cases. For example, it may be easy to predict that if we harm someone, then it will make them and those around them sad and/or angry. However, when considering more tricky situations such as an abortion, it is impossible to tell how the child’s life and its mother’s will turn out either way.

Specifically Christian forms of situational ethics of placing love above all particular principles or rules were proposed in the first half of the twentieth century by liberal theologians Rudolf Bultmann, John A. T. Robinson, along with Joseph Fletcher. These theologians point specifically to agape, or unconditional love, as the highest end. Other theologians who advocated situational ethics include Josef Fuchs, Reinhold Niebuhr, Karl Barth, Emil Brunner, and Paul Tillich. Tillich, for example, declared, “Love is the ultimate law.”

Content Curated by: Dr Shoury Kuttappa