A Story: The Work Ethic of Albert Einstein

Einstein’s most famous contribution to science, the general theory of relativity, was published in 1915. He won the Nobel Prize in 1921. Yet, rather than assume he was a finished product, Einstein continued to work and contribute to the field for 40 more years. Up until the moment of his death, Albert Einstein continued to squeeze every ounce of greatness out of himself. He never rested on his laurels. He continued to work even through severe physical pain and in the face of death.

Einstein died of internal bleeding caused by the rupture of an abdominal aortic aneurysm. One physician familiar with Einstein’s case wrote, “For a number of years he had suffered from attacks of upper abdominal pain, which usually lasted for 2-3 days and were often accompanied by vomiting. These attacks usually occurred about every 3 or 4 months.” Einstein continued to work despite the pain. He published papers well into the 1950s. Even on the day of his death in 1955, he was working on a speech he was scheduled to give on Israeli television, and he brought the draft of it with him to the hospital. The speech draft was never finished.

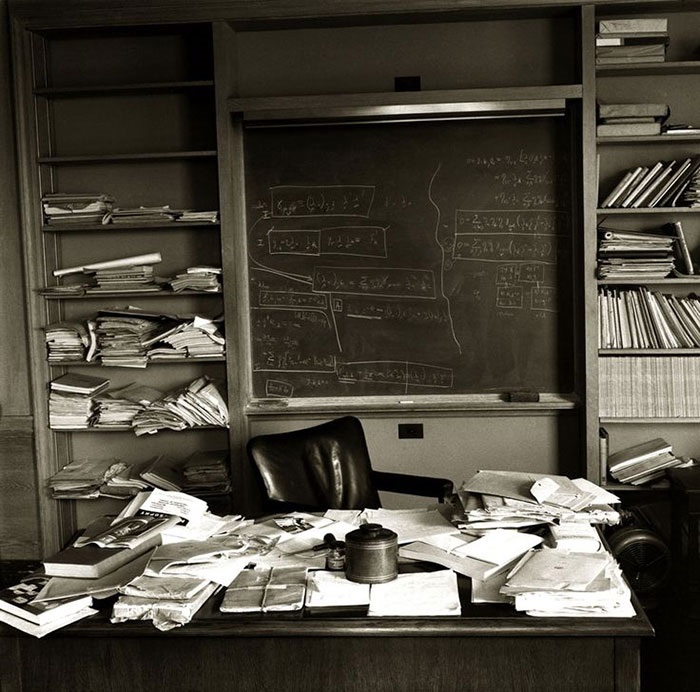

When Ralph Morse (a photographer for LIFE Magazine) walked into Einstein’s office, he snapped a photo of the desk where Albert Einstein had been working just hours before. Nobody knew it yet, but Einstein’s body would be cremated before anyone could capture a final photo of him. As a result, Morse’s photo of Einstein’s desk would soon become the final iconic image of the great scientist’s career.

Everyone has a gift to share with the world, something that both lights us on fire internally and serves the world externally, and this thing–this calling–should be something we pursue until our final breath. Whatever it is for us, our lives were meant to be spent making our contribution to the world, not merely consuming the world that others create.

Hours before his death, Einstein’s doctors proposed trying a new and unproven surgery as a final option for extending his life. Einstein simply replied, “I have done my share, it is time to go. I will do it elegantly.” We cannot predict the value our work will provide to the world. That is fine. It is not our job to judge our own work. It is our job to create it, to pour ourselves into it, and to master our craft as best we can. We all have the opportunity to squeeze every ounce of greatness out of ourselves that we can. We all have the chance to do our share.

How Do Prisoners of War Stay Alive?

Prisoners of war who have managed to survive the most brutal conditions will often claim one of the most important factors in survival is not food or water, but a sense of dignity and self–worth. In other words, the only thing that keeps some men alive in the direst of circumstances is the belief that they are worthy of being alive. Applying this to our daily lives, it makes sense that longevity would be prevalent in cultures where contribution is baked into everyday life.

For example, let’s take a culture where it’s common to go to the neighbour’s house and talk each night. During a face–to–face conversation, we have to either contribute or sit silently in the corner like a weirdo. The act of contributing to a conversation, no matter how simple it seems, allows us to derive a small sense of self–worth. Being a meaningful part of a conversation makes us feel like were a worthwhile part of the neighbour’s life. When we add up all of the small contributions to the many conversations over the years, it’s easy to see how we can develop a strong sense of self–worth when we live in a culture where contribution is typical.

Contributing vs. Consuming

We alter the course of other’s lives by what we create and contribute. When we speak or write or act, we influence the people around us. When we contribute something to the world, we matter. And thus the act of creating enhances our feelings of self–worth.

That is often lost online as it is becoming increasingly easy to spend our time consuming rather than contributing. Most of the time on those devices and networks is spent consuming what someone else has created rather than contributing our own ideas and work. The result, I believe, is that our sense of self–worth slowly dwindles.

These contributions don’t have to be major endeavours. Cooking a meal instead of buying one. Playing a game instead of watching one. Writing a paragraph instead of reading one. We do not have to create big contributions, but just need to live out small ones each day.

Too often we spend our lives visiting the world instead of shaping it. We can be an adventurer, an inventor, an entrepreneur, an artist. Contributing and creating doesn’t just make us feel alive, it keeps us alive.

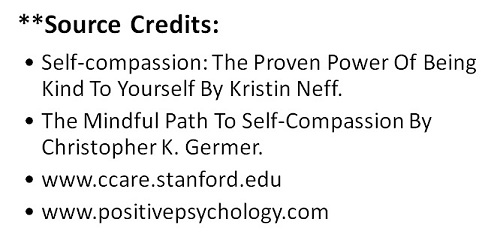

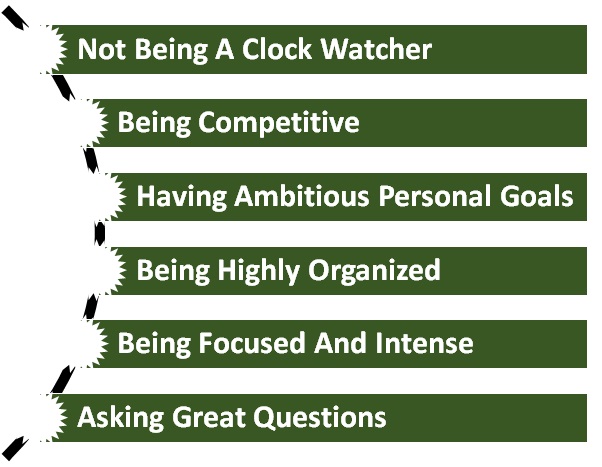

Elements of A Strong Work Ethic

But when can we describe our work ethic to be good and strong? Some elements that serve as a solid foundation for a strong work ethic are:

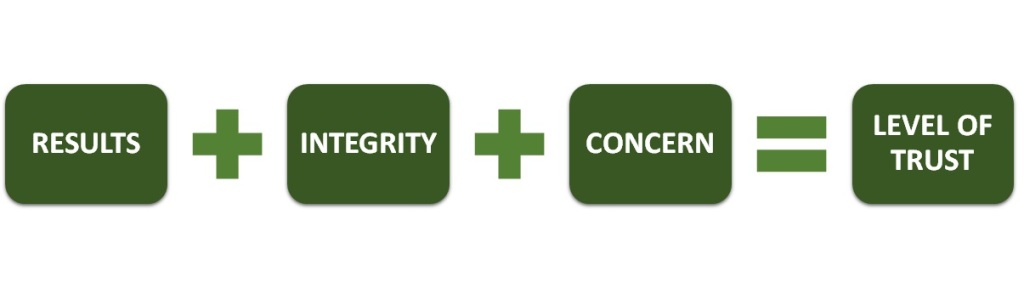

Integrity: . . . . . . . . Its greatest impact is seen in our relationships with the people around us, which is why integrity is seen as one of the most important ingredients of Trust. According to Robert Shaw, you can earn a certain level of trust if you are able to achieve results while demonstrating concern for others and acting with integrity the whole time. Hence, the formula:

Acting with integrity, in this context, also means behaving in a consistent manner. For example, if we are part of a team, our behaviour should be in tune with everyone, in accordance with a clear set of guidelines in working together toward a clear purpose.

Emphasis on Quality of Work: . . . . . . . . If we show dedication and commitment to coming up with very good results in our work, then our work ethic will definitely shine.

While some employees do only the barest minimum, or what is expected of them, there are those who go beyond that. They do more, they perform better, and they definitely go the extra mile to come up with results that surpass expectations. Clearly, these employees are those who belong to the group with a solid work ethic.

Professionalism: . . . . . . . . The word “professionalism” is often perceived as something that is too broad or wide in scope, covering everything from our appearance to how we conduct ourselves in the presence of other people. It is so broad and seemingly all-encompassing that many even go so far as to say that professionalism equates having a solid work ethic.

Discipline: . . . . . . . .Work ethic is something that emanates from within. We can tell someone to do this and that, be like this and like that, over and over, but if they do not have enough discipline to adhere to the rules and follow through with their performance, then there is no way that they can become the productive employees that the company wants.

Sense of Responsibility: . . . . . . . . The moment we became part of the organization and were assigned tasks and duties, we have a responsibility that we must fulfil. If we have a strong work ethic, we will be concerned with ensuring that we are able to fulfil our duties and responsibilities. We will also feel inclined to do our best if we want to get the best results.

Sense of Teamwork: . . . . . . . . As an employee, we are part of an organization. We are simply one part of a whole, which means we have to work with other people. If we are unable to do so, this will put our work ethic into question. Work ethic is also continuously shaped by relationships, specifically on how we are able to handle them in achieving goals, whether shared or individual.

Other traits of good work ethics include:

Content Curated By: Dr Shoury Kuttappa