Self-differentiation is a word we probably do not hear in everyday usage. But it is a crucial process to living (and eating) well. It is happening when we hear people speaking their minds with thoughtful conviction even though others might disapprove. It is lacking when someone spends their life rebelling against the views and values of parents/ colleagues and clinging to their opposite. It is missing when someone stifles feelings and thoughts in fear of hurting others or being rejected or shamed by them.

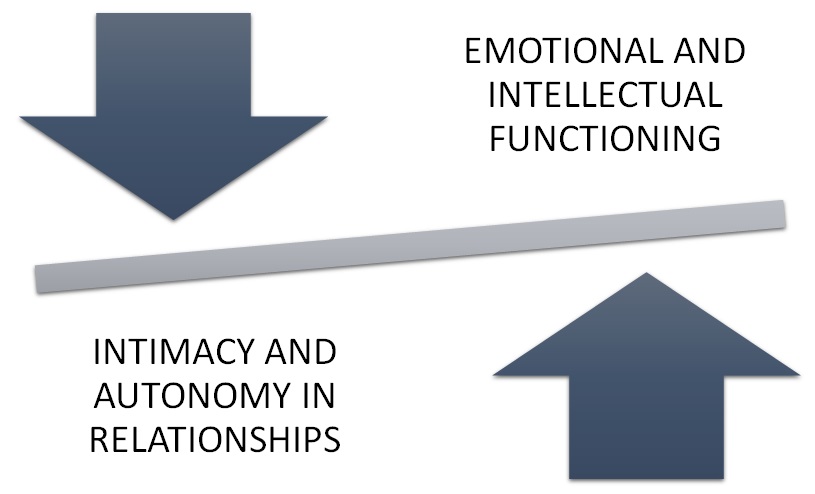

Differentiation of self was defined by Murray Bowen (Psychiatrist, Professor- Georgetown University) in 1978 as the degree to which one is able to balance: (a) emotional and intellectual functioning, and (b) intimacy and autonomy in relationships.

His theory has two major parts.

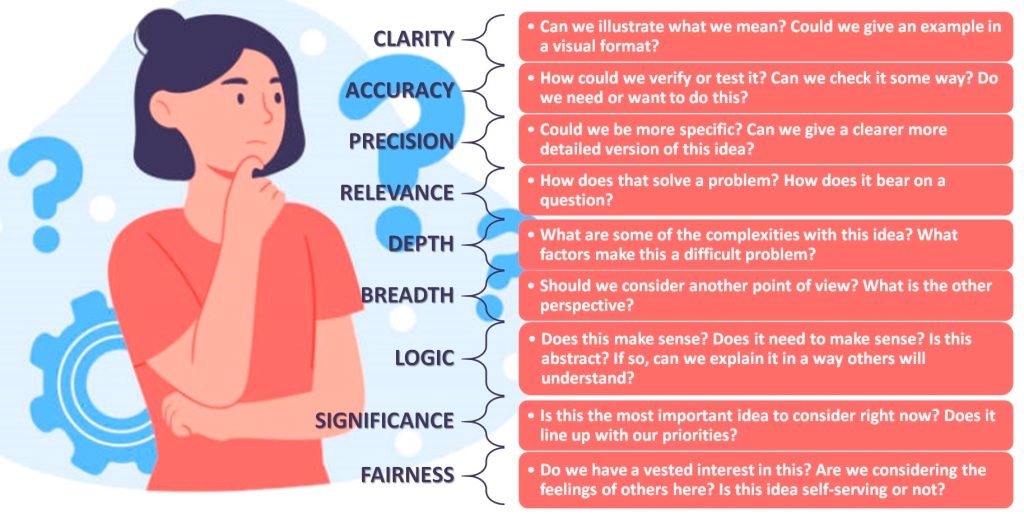

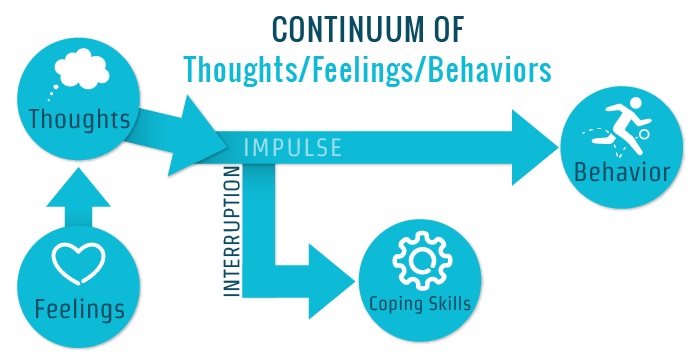

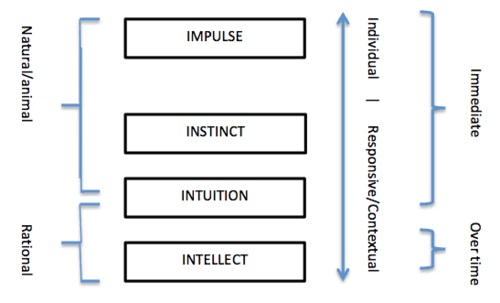

1) Differentiation of self is the ability to separate feelings and thoughts. Undifferentiated people cannot separate feelings and thoughts; when asked to think, they are flooded with feelings, and have difficulty thinking logically and basing their responses on that.

2) Further, they have difficulty separating their own from others’ feelings; they look to family to define how they think about issues, feel about people, and interpret their experiences.

On an intrapsychic level, differentiation refers to the ability to distinguish thoughts from feelings and to choose between being guided by one’s intellect or one’s emotions.

Self-differentiation involves being able to possess and identify our own thoughts and feelings and distinguish them from others. It is a process of not losing connection to self while holding a deep connection to others, including those we love whose views may differ from ours. For Example- if we grow up in a family in which everyone maintains attachment (or has only brief disconnects) in spite of having different thoughts and feelings, we can begin to self-differentiate.

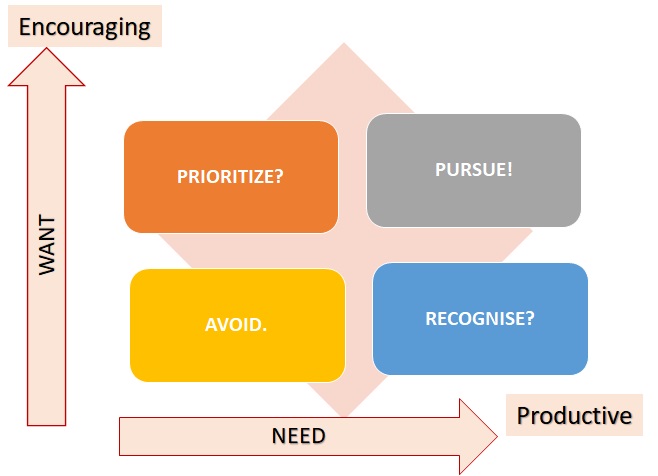

Greater differentiation allows one to experience strong affect or shift to calm, logical reasoning when circumstances dictate. Flexible, adaptable, and better able to cope with stress, more differentiated individuals operate equally well on both emotional and rational levels while maintaining a measure of autonomy within their intimate relationships. Highly differentiated individuals are thought to demonstrate better psychological adjustment.

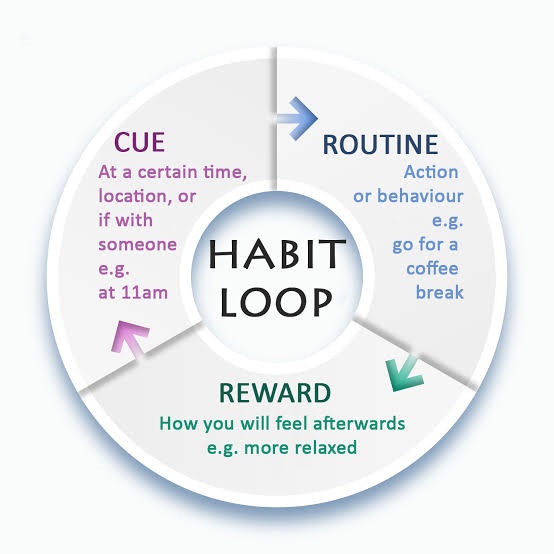

In contrast, poorly differentiated persons tend to be more emotionally reactive, finding it difficult to remain calm in response to the emotionality of others. With intellect and emotions fused, they tend to make decisions based on what “feels right”; in short, they are trapped in an emotional world. Less differentiated individuals experience greater chronic anxiety.

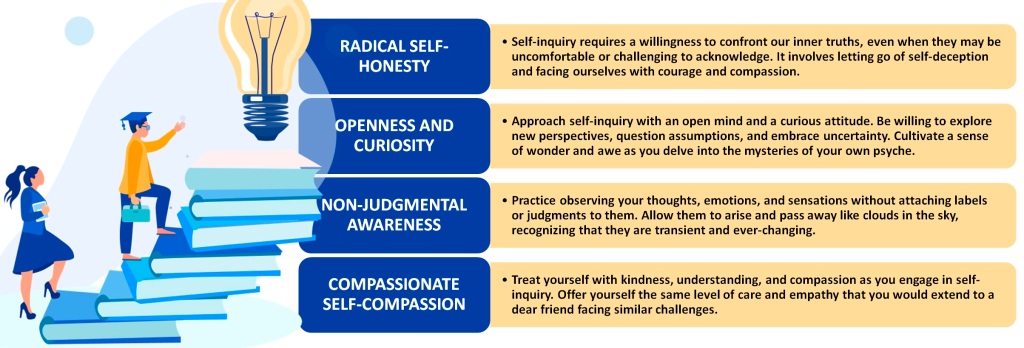

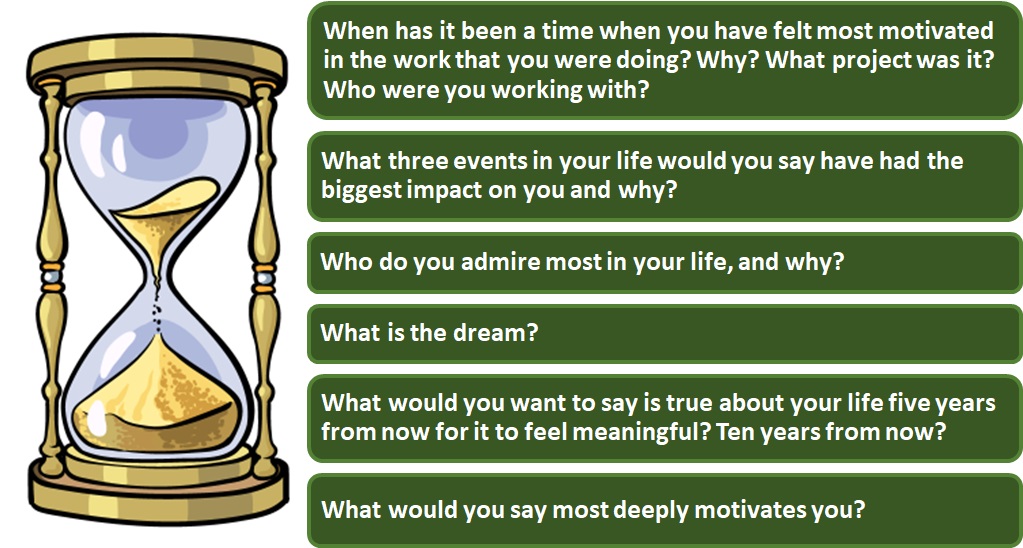

From a process orientation, differentiation is an active, ongoing process of connecting to and honouring our own experience, acting in integrity with our values, and engaging in collaboration with others to meet needs. When differentiated, we are able to identify our needs and preferences in any given situation and to speak up for them when necessary. We regularly and explicitly clarify boundaries. We are able to manage the reactivity and discomfort that comes from either risking greater intimacy or potential separation and conflict.

Not only do problems with lack of self-differentiation make healthy adult relationships impossible, but they cause tremendous inner turmoil which can often lead to comfort eating. We may get furious because we feel controlled by someone who wants us to do something we do not wish to do but believe we are unsafe expressing our feelings openly. Or we may silence ourselves around others and feel inauthentic, unheard, or invisible, and with needs unmet, seek food for solace.

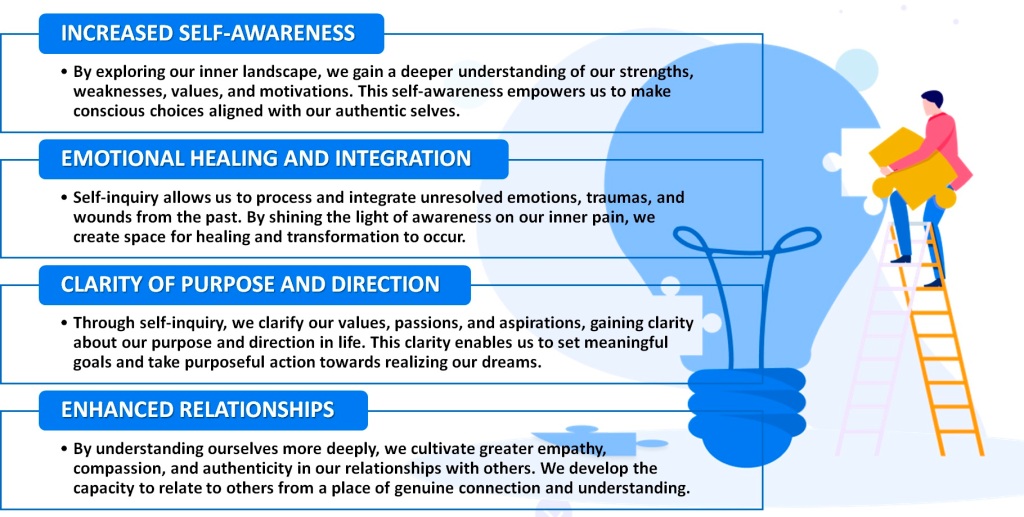

Here are some core skills and behaviors that signify and support differentiation to cultivate and watch for:-

- Groundedness and clarity about our identity; confidence in our innate goodness and lovability.

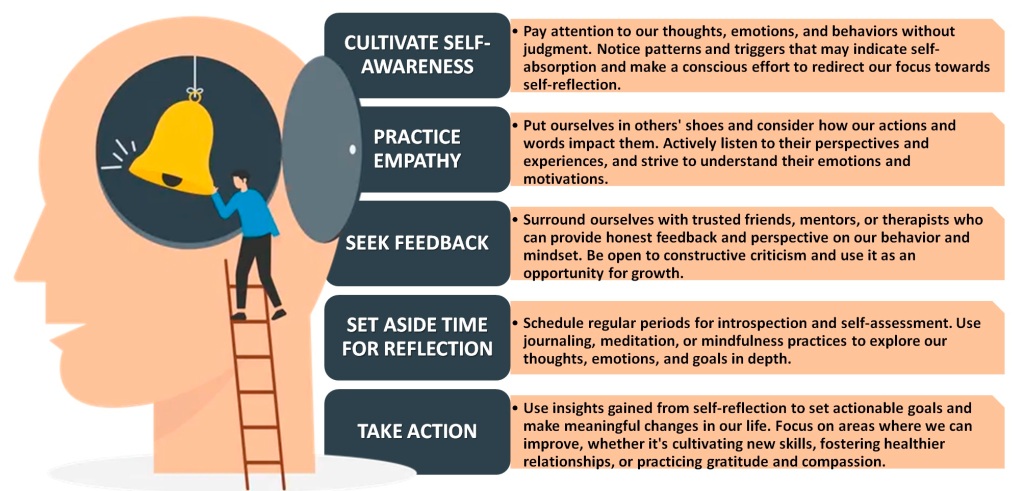

- Self-awareness, self-empathy, self-regulation/soothing remain accessible and consistent throughout a given day.

- Self-responsibility: an ability to share unmet needs without blame, criticism, or demands.

- An ability to meet differences with respect, curiosity, empathy, or celebration.

- An ability to listen with empathy in interactions we perceive as difficult or challenging.

- An ability to make changes within or to end relationships in which collaboration and mutual respect are not met.

- Consistent engagement in activities and behaviours that support our thriving.

- Having multiple trusted strategies to meet any given need; not expecting to meet any need with just one person or one strategy.

- A consistent sense of meaning and purpose.

- A consistent and confident sense of autonomy and agency.

- An ability to express authentically while considering the needs of others and risking conflict.

- Mindfulness practice: noticing your experience with compassion; having an ability to identify your intention, feelings, needs, and requests in any given moment.

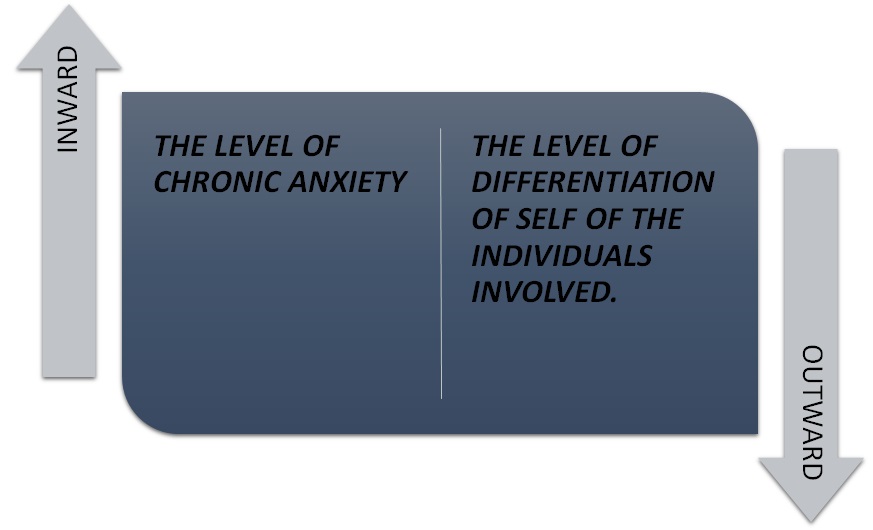

Emotional fusion refers to an emotional intertwining between people and or between people and other animals or between people and objects. This is an attachment that is a part of all relationships but varies in quantity depending on two variables: the level of chronic anxiety and the level of differentiation of self of the individuals involved.

A high degree of fusion or attachment reflects a high degree of sensitivity of people to each other and when sufficiently intense takes one of two forms: “I can’t do without you” or “I can’t stand to be around you.” Regardless of the external form fusion takes, it reflects a state of “we-ness” in that people believe, to some extent, that they must feel alike, think alike, and behave alike.

Anger and over-compliance, for example, are two sides of the same coin. Both are the result of fusion or the inability to function, the result of having thoughts and actions determined by others. We should take pride in our emotions but be wary of the forces that are trying to manipulate them. We must always balance emotion with reason.

Content Curated By: Dr Shoury Kuttappa.