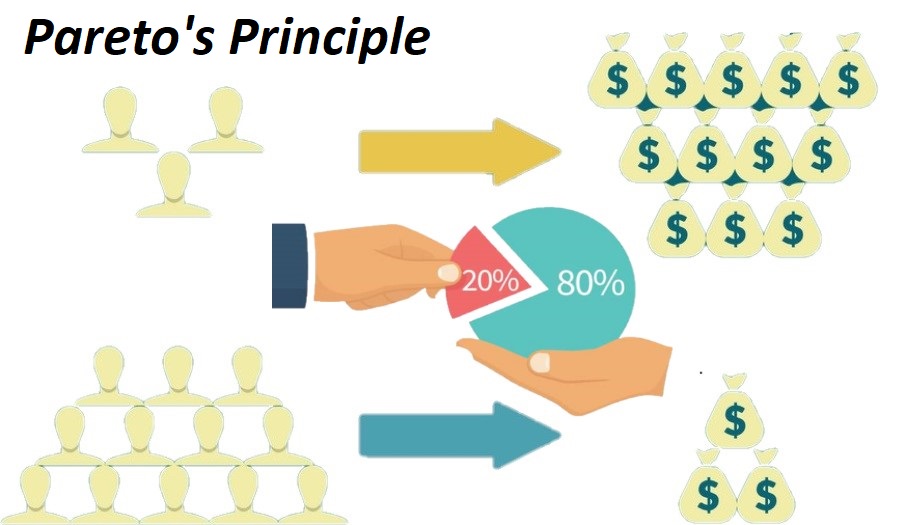

The Pareto principle states that for many outcomes, roughly 80% of consequences come from 20% of causes (the “vital few”). Other names for this principle are the 80/20 rule, the law of the vital few, or the principle of factor sparsity.

Management consultant Joseph Juran developed the concept in the context of quality control and improvement, naming it after Italian economist Vilfredo Pareto, who noted the 80/20 connection while at the University of Lausanne in 1896. In his first work, Cours d’économie politique, Pareto showed that approximately 80% of the land in Italy was owned by 20% of the population. The Pareto principle is only tangentially related to Pareto efficiency. More generally, the Pareto Principle is the observation (not law) that most things in life are not distributed evenly. It can mean all of the following things:

The Uneven Distribution

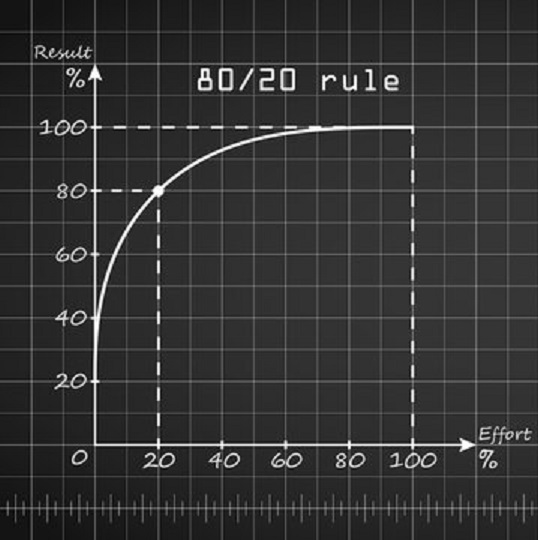

What does it mean when we say that things aren’t distributed evenly? The key point is that each unit of work (or time) doesn’t contribute the same amount. In a perfect world, every employee would contribute the same amount, every bug would be equally important, every feature would be equally loved by users. Planning would be so easy. But that isn’t always the case.

The 80/20 principle observes that most things have an unequal distribution. Out of 5 things, perhaps 1 will be good. That good thing/idea/person will result in majority of the impact of the group. Of course, this ratio can change. It could be 80/20, 90/10, or 90/20 (the numbers don’t have to add to 100 even). The key point is that most things are not 1:1, where each unit of input (effort, time, labour) contributes exactly the same amount of output.

The Upside of the 80/20 Principle

When applied to life and work, the 80/20 Rule can help separate the vital few from the trivial many. For example, business owners may discover the majority of revenue comes from a handful of important clients. The 80/20 Rule would recommend that the most effective course of action would be to focus exclusively on serving these clients (and on finding others like them) and either stop serving others or let the majority of customers gradually fade away because they account for a small portion of the bottom line.

The 80/20 Rule is like a form of judo for life and work. By finding precisely the right area to apply pressure, we can get more results with less effort.

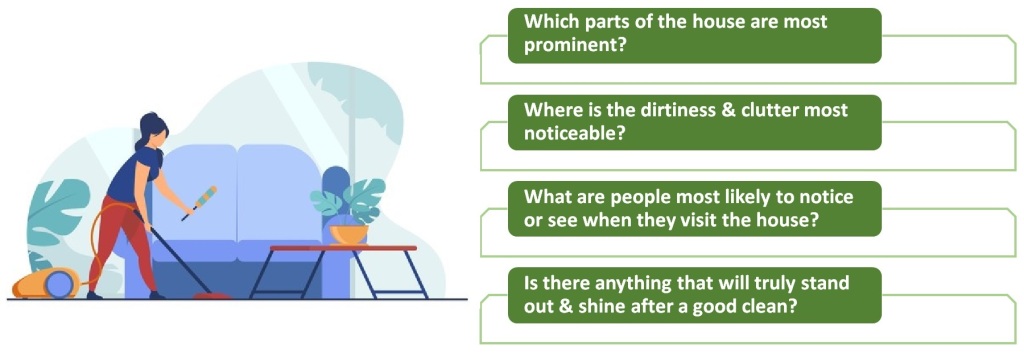

An Everyday Example – Home Cleaning

Let us say we are cleaning our house. Some people might approach this by distributing their effort evenly across a variety of tasks, including dusting, vacuuming, and mopping each room. But this probably is not very efficient — it would take many hours to get everything done. The Pareto Principle tells us that 80% of how clean our house appears comes down to 20% of our cleaning efforts. Again, we don’t need to work out exactly what 20% of our cleaning looks like. But we do need to ask questions like:

We might conclude that giving the house a quick vacuum, clearing away the bulk of the clutter, and dusting down the main surfaces makes a huge difference. Or perhaps we figure that visitors will spend most of their time in the living room and dining room, so we will focus on them and only give other rooms a cursory clean? But giving every mirror a perfect polish and removing every speck of dust from the house might not make such a big difference to the overall result.

The Downside of the 80/20 Principle

We get one, precious life. How do we decide the best way to spend our time? Productivity concepts will often suggest that we focus on being effective rather than being efficient.

Efficiency is about getting more things done. Effectiveness is about getting the right things done. In other words, making progress is not just about being productive. It’s about being productive on the right things. But how do we decide what the right things are? The 80/20 Rule states that, in any particular domain, a small number of things account for the majority of the results. The point is that the majority of the results are driven by a minority of causes. There is a downside to the 80/20 principle, and it is often overlooked. To understand this pitfall, here is a story.

A Story: Audrey Hepburn- A New Path

Audrey Hepburn was an icon. Rising to fame in the 1950s, she was one of the greatest actresses of her era. In 1953, Hepburn became the first actress to win an Academy Award, a Golden Globe Award, and a BAFTA Award for a single performance- her leading role in the romantic comedy Roman Holiday. Even today, over half a century later, she remains one of just 15 people to earn an “EGOT” by winning all four major entertainment awards: Emmy, Grammy, Oscar, and Tony. By the 1960s, she was averaging more than one new film per year and, by everyone’s estimation, she was on a trajectory to be a movie star for decades to come.

But then something funny happened- she stopped acting. Despite being in her 30s and at the height of her popularity, Hepburn basically stopped appearing in films after 1967. She would perform in television shows or movies just five times during the rest of her life. Instead, she switched careers. She spent the next 25 years working tirelessly for UNICEF, the arm of the United Nations that provides food and healthcare to children in war-torn countries. She performed volunteer work throughout Africa, South America, and Asia.

Hepburn’s first act was on stage. Her next act was one of service. In December 1992, she was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom for her efforts, which is the highest civilian award of the United States.

The Shortcoming of the 80/20 principle:

For a moment, let us all Imagine it is 1967. Audrey Hepburn is in the prime of her career and trying to decide how to spend her time. If she uses the 80/20 Rule as part of her decision-making process, she will discover a clear answer- do more romantic comedies. Many of Hepburn’s best films were romantic comedies. They attracted large audiences, earned her awards, and were an obvious path to greater fame and fortune. Romantic comedies were effective for Audrey Hepburn.

In fact, even if we take into account her desire to help children through UNICEF, an 80/20 analysis might have revealed that starring in more romantic comedies was still the best option because she could have maximized her earning power and donated the additional earnings to UNICEF.

Of course, that’s all well and good if she wanted to continue acting. But she didn’t want to be an actress. She wanted to serve. And no reasonable analysis of the highest and best use of her time in 1967 would have suggested that volunteering for UNICEF was the most effective use of her time. This is the downside of the 80/20 Rule: A new path will never look like the most effective option in the beginning.

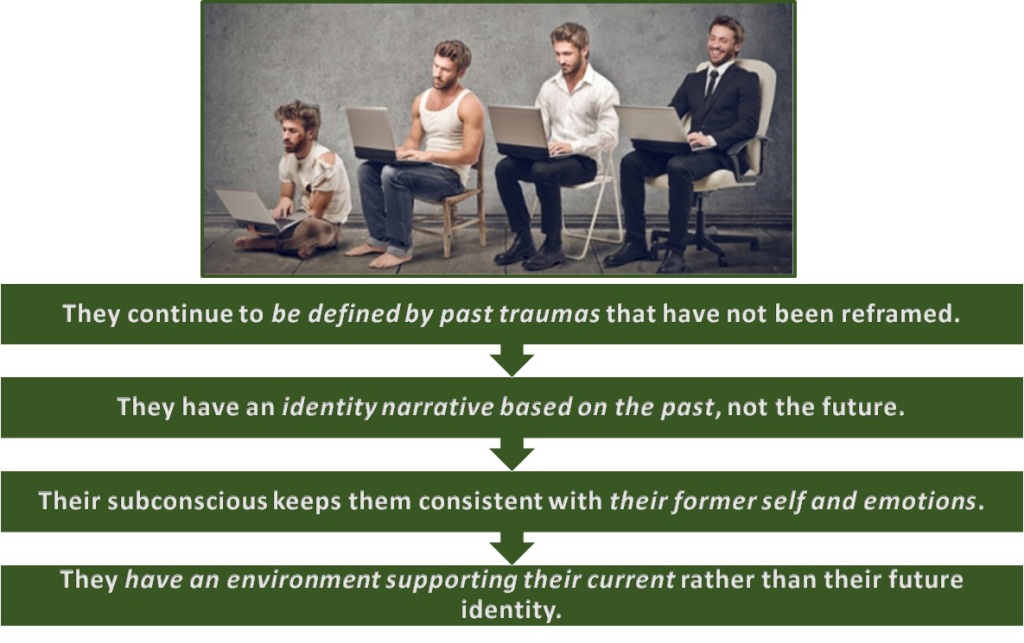

Optimizing for the Past or the Future

Let us look at another example. Jeff Bezos, the founder of Amazon, worked on Wall Street and climbed the corporate ladder to become senior vice-president of a hedge fund before leaving it all in 1994 to start the company. If Bezos had applied the 80/20 Rule in 1993 in an attempt to discover the most effective areas to focus on in his career, it is virtually impossible to imagine that founding an internet company would have been on the list. At that point in time, there is no doubt that the most effective path—whether measured by financial gain, social status, or otherwise—would have been the one where he continued his career in finance.

The 80/20 Rule is calculated and determined by our recent effectiveness. Whatever seems like the “highest value” use of time in any given moment will be dependent on our previous skills and current opportunities. The 80/20 Rule will help us find the useful things in our past and get more of them in the future. But if we don’t want our future to be more of the past, then we need a different approach. The downside of being effective is that we often optimize for our past rather than for our future.

The Way Forward

Given enough practice and enough time, the thing that previously seemed ineffective can become very effective. We get good at what we practice. When Audrey Hepburn dialed down her acting career in 1967, volunteering didn’t seem nearly as effective. But three decades later, she received the Presidential Medal of Freedom—a remarkable feat she is unlikely to have accomplished by acting in more romantic comedies.

The process of learning a new skill or starting a new company or taking on a new adventure of any sort will often appear to be an ineffective use of time at first. Compared to the other things you already know how to do, the new thing will seem like a waste of time. It will never win the 80/20 analysis. But that doesn’t mean it’s the wrong decision.

Content Curated By: Dr Shoury Kuttappa