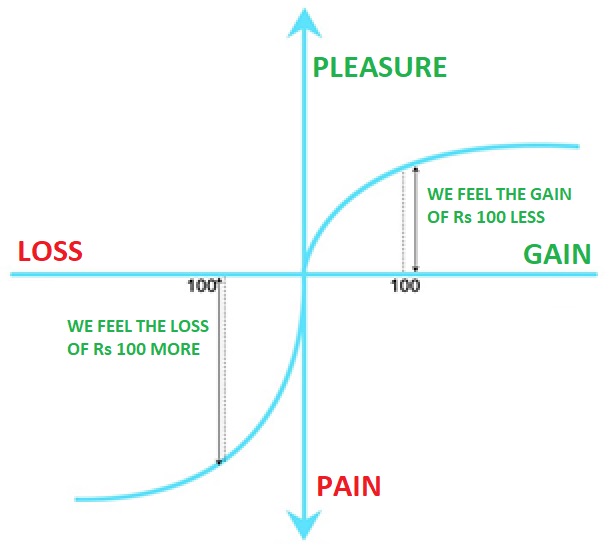

***Continued from Chapter 01 (Covered previously: Meaning, Progressive & Degenerative impact, Loss Aversion, Psychological Roots)

Link to Chapter 01:

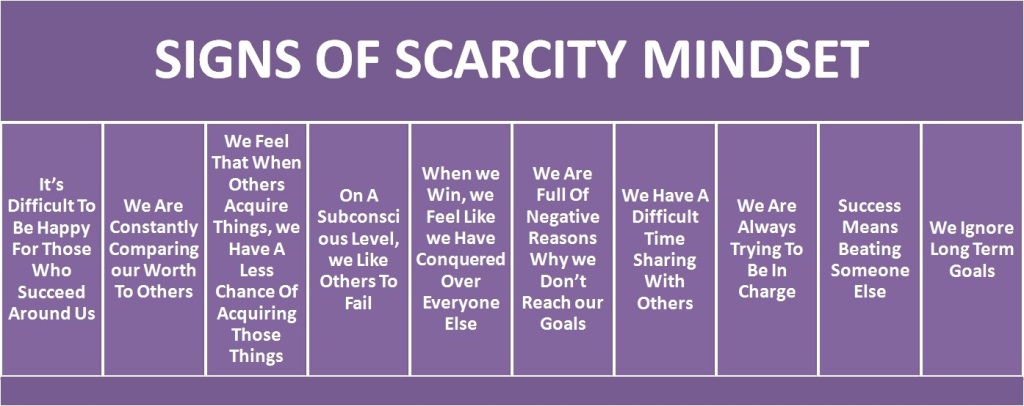

Forms in which Scarcity Mindset may Manifest

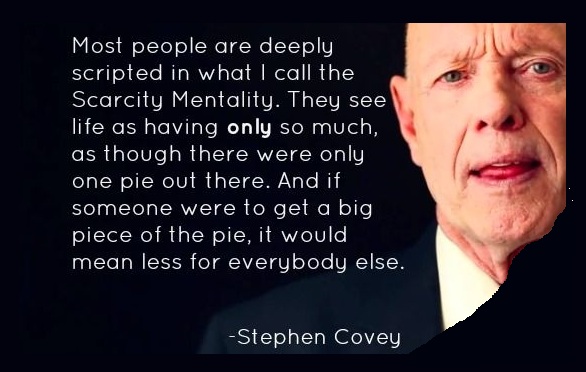

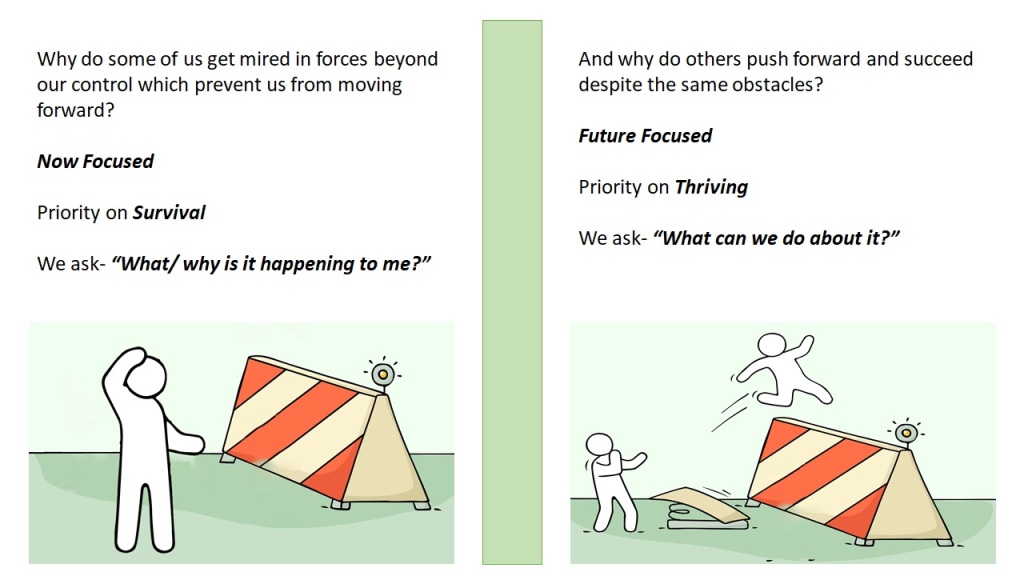

A) Believing That Situations Are Permanent: . . . . . . . . . . We think “Well, that’s just the way it is” instead of changing our frame of mind and seeking out our own happiness. Thinking this way depletes our energy, harms our self-esteem, and makes life a burden in general. Nothing is permanent. There are moments in our lives that will take our breath away. An abundant mentality thinks this way and sees life as dynamic and mouldable; something that is ours to shape and make to our liking. Perhaps most importantly, an abundant mentality sees life as an adventure.

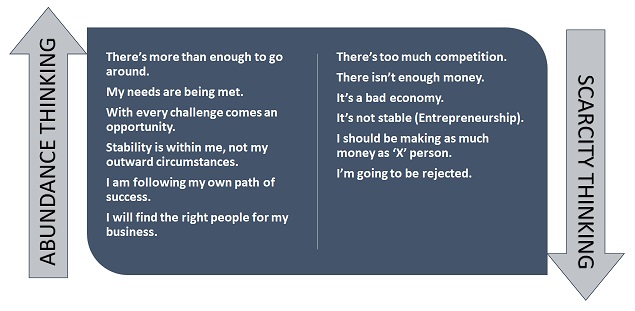

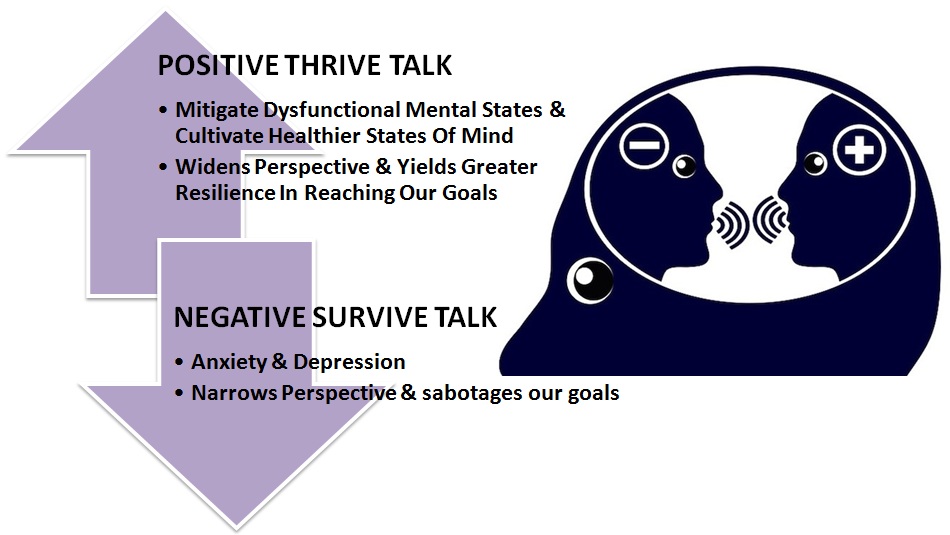

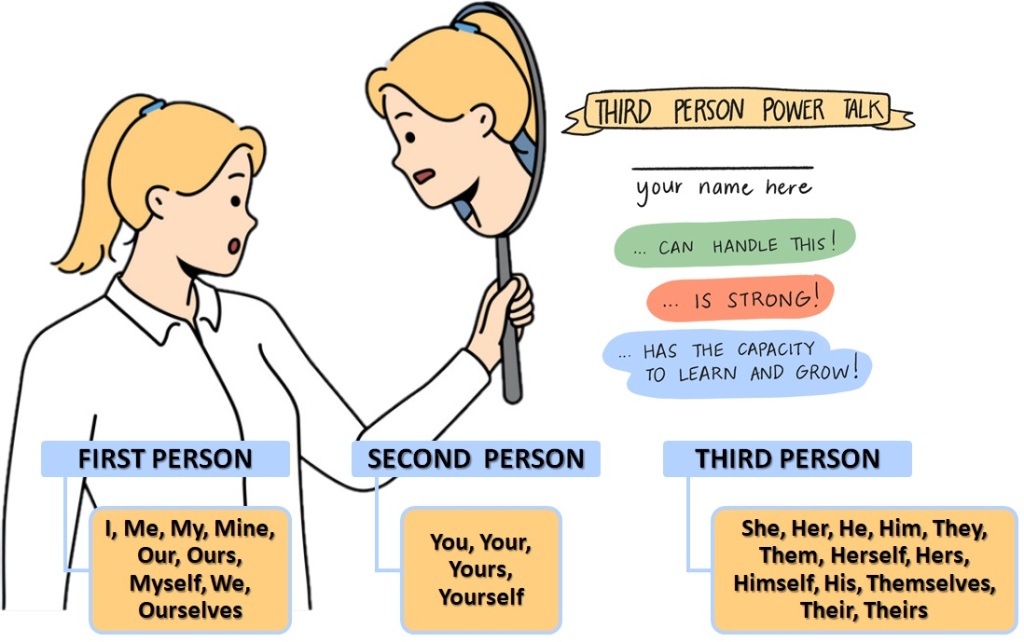

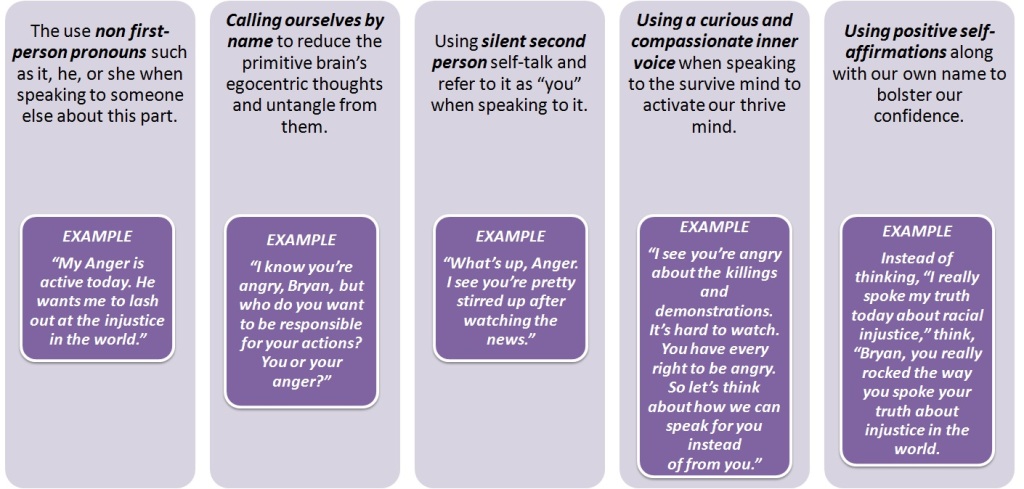

B) Using Thoughts And Words Of Scarcity: . . . . . . . . . . What we tell ourselves ultimately becomes an extension of us if left unchecked. When negative thoughts arise, which is quite natural, one way is to become an observer and refuse to engage with them. Everyone is afraid of rejection. However, a recent study from Stanford reports that people tend to overestimate their chances of being rejected. Furthermore, even if we do happen to get rejected usually it is just a matter of widening our pool and continuing along our path. Rejection doesn’t happen as often as we tend to think—and even if does, it’s simply a matter of moving forward.

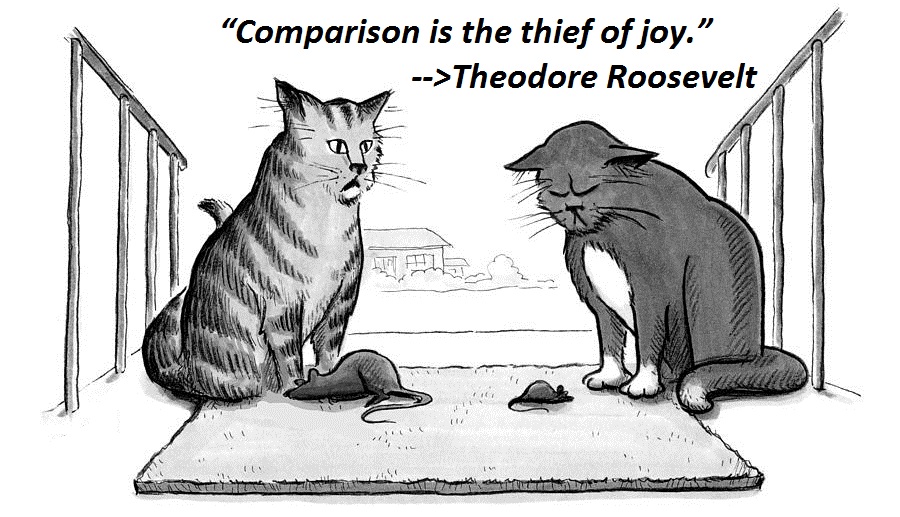

C) Comparison/ Being Envious Of Others: . . . . . . . . . . This kills gratitude and stokes the fire of scarcity. When it comes to bettering our circumstances, we can consciously choose to devote our time and energy towards doing so and not wasting it on envious thoughts and feelings. Comparing ourselves to other people is a sure-fire way to stay stuck. The truth is we have no idea what the financial situation of another person or business is. Furthermore, everyone’s definition of success is different. It is important that we define what success means to us so that we can act accordingly.

D) Not Being Generous: . . . . . . . . . . When one lives with a scarcity mindset, they are more apt to “skim off the top” with time, money, relationships, etc. These actions have unintended consequences and make it less likely to generate the positive effects that we seek in our own lives. If we believe in lack, by default, we believe in giving less of ourselves. This does not necessarily mean money, it also means being generous by smiling, saying kind words, investing our time in people, and simply serving a greater good.

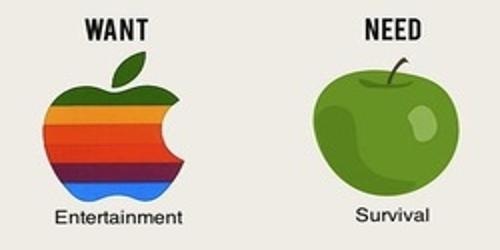

E) Overindulgence: . . . . . . . . . . When one thinks in terms of scarcity, they are most likely to overeat, overspend and, in general, become more gluttonous. This is because of another temptation: instant gratification. When we think of money as a scarce resource, there is a tendency to use that resource for pleasure. But pleasure could reinforce the scarcity mindset that one already possesses.

For instance: Let us say that we are having a tough day, feel down on ourselves, and need something positive. We could do something constructive like spending some time with the family (abundance)…or…we could buy that new, cool gadget that we have wanted with our credit card (scarcity). Here the abundant choice has absolutely nothing to do with money. We are focusing our time on what matters the most and not succumbing to some temporary pleasure that, while good for a time, does nothing more than add to the notion that we simply do not have enough.

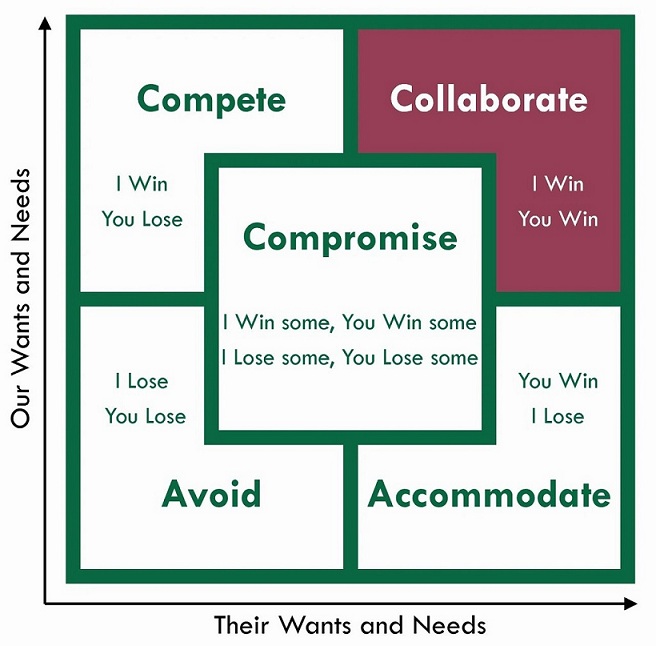

F) There is too much competition: . . . . . . . . . .We live in an incredibly abundant universe, which means that there are plenty of clients, press opportunities, deals, contracts, blog readers and customers to go around. The best we can do is take care of our side of the street and focus on how our business serves people. Furthermore, we are living in a “share economy” where collaboration has taken centre stage. A classic example is AirBnB and Uber. The truth is this kind of economy, where people are sharing resources, talents, and skills rather than competing with one another, has opened the door for more opportunity within the markets.

G) There is not enough resources/ Economy is Bad: . . . . . . . . . .Lack of resources and funds stops people from doing a lot. Sometimes people use this as an automatic excuse out of fear. There is always someone making money regardless of the state of the economy. Those who curb their scarcity mentality are trained to see opportunity in everything. Many people found themselves in a position of having to create their own businesses because they could not find forms of traditional employment. We also have women starting businesses at a faster rate than ever before. Much of this came as a result of a bad economy.

It is like the old saying goes, Necessity is the mother of invention. It just so happens that often those inventions lead to abundance. In an effort to feel comfortable and secure, many would-be entrepreneurs forego creating businesses despite their desires because they feel like traditional employment is more secure.

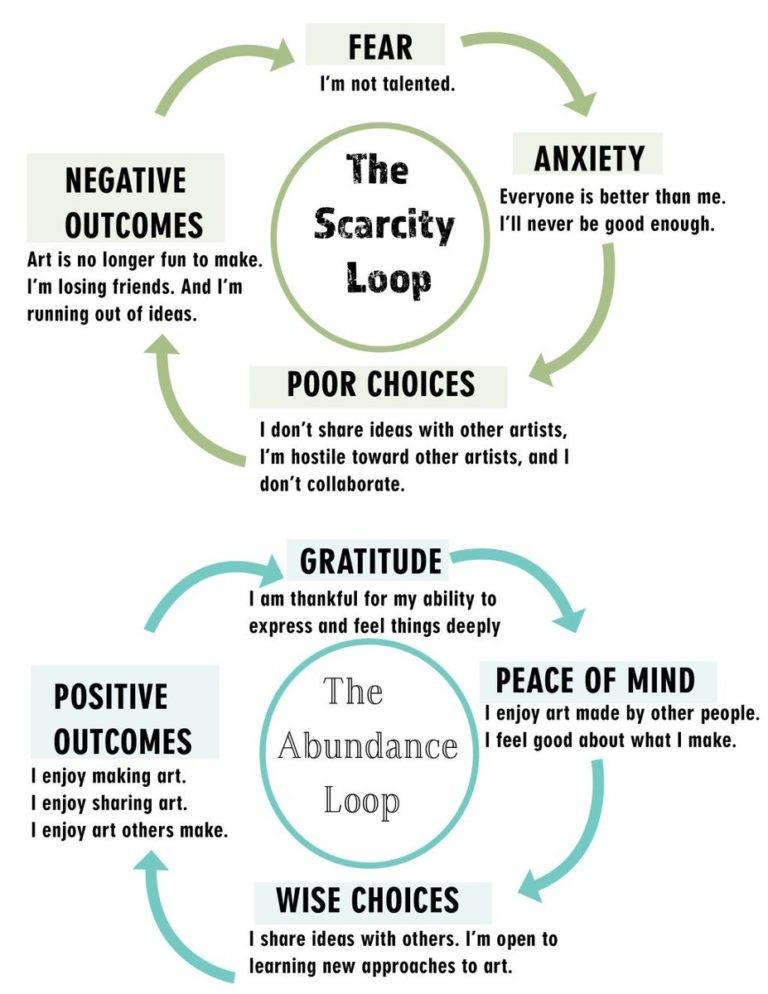

Scarcity And Abundance Loops at Play (Using an example of Art)

Scarcity Mindset At Play (With Instances around us To Support Recognition)

Many organizations use psychological alteration to influence favorable decisions to maximize profit. Understanding how scarcity works allow us to be aware of such tactics and be prepared. Some examples of these are:

A) Time-limited scarcity: . . . . . . . . . In time-limited offers, the user needs to decide before a set deadline- this adds a sense of urgency to the decision-making process.

Instances: – – – – The most common real-life scenario is waiting until the last minute to complete projects/study for exams. In such cases, focus and attention levels increase and so does prioritizing. Flipkart indicates the count-down timer showing when the discounted price ends, which influences the user to grab the product deal before it expires.

B) Quantity-limited scarcity: . . . . . . . . .This is considered more powerful than time-limited scarcity, as availability depends on popularity or supply and is therefore unpredictable. This can be of the following types:

i) Limited Supply: – – – Items with limited supply are valued and desired more. Oil prices soar in countries like India due to limited supply, whereas the opposite is true in countries like Kuwait, Saudi due to availability. Amazon showcases “only 2 left in stock”, representing a product’s diminishing availability thus influencing the user to make the decision quickly.

ii) Popularity: – – –The popularity of an item represents the social proof that it must be good and valuable and triggers us to grab the deal. Myntra is used to showcase “18 people added this item to their cart” in their product page which informs the user that the product they are viewing is popular and might get over soon.

iii) Limited Supply and Popularity: – – – – This is more effective than the above two. Not only do we desire an item when it is scarce, but we also want it, even more, when we have to compete for it. Stamps and antique pieces are quite valuable because they are unique and cannot be easily supplied. People then outbid each other to possess the item which makes the value of the item increase significantly.Booking.com showcasing “only 6 rooms left” along with “6 people are looking at this moment”.

C) Access-limited scarcity:: . . . . . . . . .When access to certain information is limited, it is perceived as having higher value because of exclusivity, especially when it’s bound to social status.

Instances: – – – – Priority pass membership provides access to special airport lounges which include free complimentary food, alcohol, Wi-fi, and discounts on shopping. One Plus implemented an invite-only sales strategy which helped them create a great buzz in the market. People ‘lucky enough’ to be invited felt more privileged. This resulted in over 25 million visits to the site and close to a million sales in less than a year after launch.

D) Ban or Censorship:: . . . . . . . . .When anything interferes with our prior access to some item, we desire it more and want to have even more than before.

Instances: – – – – The ‘Romeo and Juliet’ effect highlights that the greater the parental disapproval of a relationship is, the more that relationship intensifies.

E) One-of-a-kind Special Events:: . . . . . . . . .‘Now or never’ scenarios. We seek to experience ‘once in a lifetime opportunities’, because of their unavailability later on.

Instances: – – – – Reliance Jio provided great introductory offers in India at the time of its launch which attracted a lot of customers. In Kanchipuram, the idol of Aththi Varadar is available for darshan once every 40 years for only a few days. Lakhs of devotees visit the temple to experience this once in a lifetime opportunity.

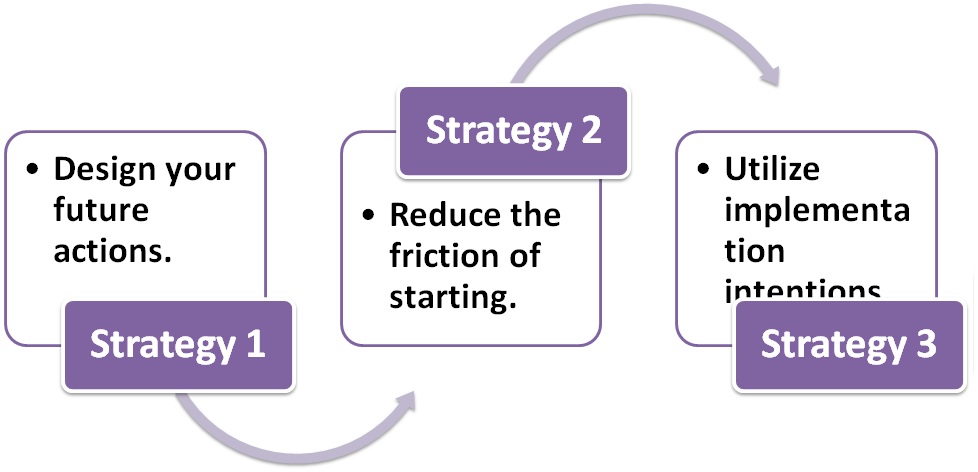

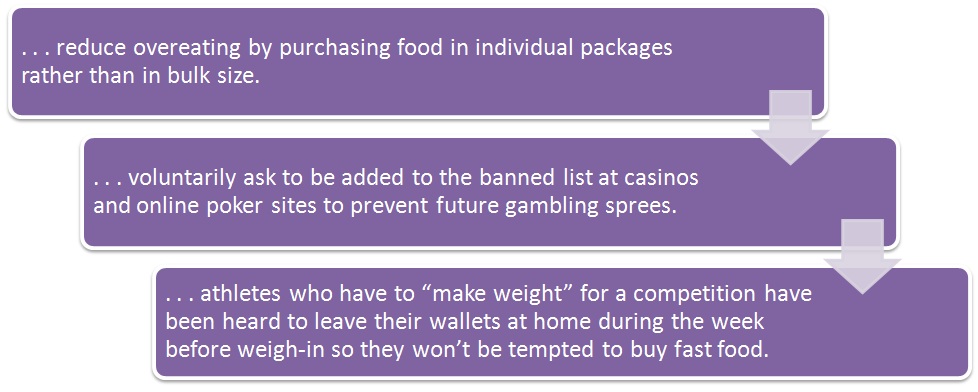

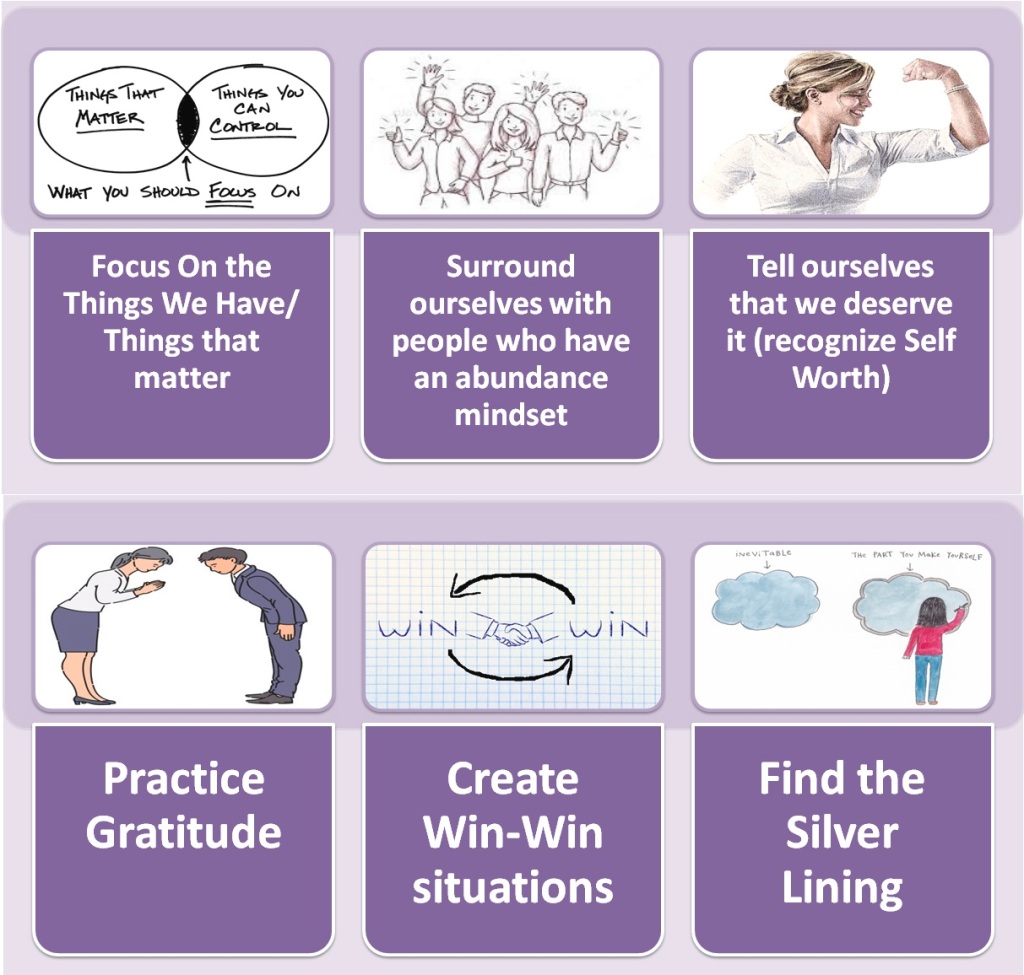

Ways to deal with Scarcity Mindset

Content Curated By: Dr Shoury Kuttappa