***Continued from Chapter 01 (Covered previously: Meaning & Interpretation Of Accountability, The Blame Game, Its Impact)

Link to Chapter 01:

The demand for rights has become extremely popular, but when it comes to dealing with responsibility and accountability, we lag far behind, a gap that accounts for increase in blaming and rights proclaiming, but very few instances of personal responsibility and accountability. The better the case for victimization, the more visibility and exposure we get, and, consequently, the greater the psychological or monetary reward we receive.

The “blame game,” and the “thirst for exposure,” are just two symptoms of a widespread “responsibility avoiding” syndrome, which have afflicted individuals, groups and organizations as well. A majority of people in organizations today, when confronted with poor performance or unsatisfactory results, immediately begin to formulate excuses, rationalizations, and arguments for why they cannot be held accountable for the problems.

Ways To Move Away From The Blaming

What is the accountability ladder and why is it important?

As is with all behavior – it starts with the leadership. The level of accountability within an organization is directly related to the level of accountability that the leaders display. Leaders can never afford to forget the actions that they initiated or created. It is not good enough to ask someone to do something and then ‘forget’ to ask if it was done or for an update on the progress of the action. If we do, the underlying message we are communicating is that the action was not important. Accountability starts at the top. The state of accountability is a reflection of the leadership culture.

So how do we move towards a positive accountability culture – how do we help people to become more accountable? The first thing is to establish where ‘the locus of control’ exists in the organization. Do people ‘feel’ like they have permission to be accountable or are all decisions made by the leadership?

Accountability and Engagement.

Next is the relationship between accountability and engagement. Getting our people engaged in their work is an important aspect of accountability and sets the stage for a healthy, productive work environment. The level of ownership someone takes for the job they do is key. An engaged employee can yield up to 57 percent more discretionary effort than one who is not engaged. Three important strategies for creating employee engagement include:

WIIFM (What’s in it for me?)

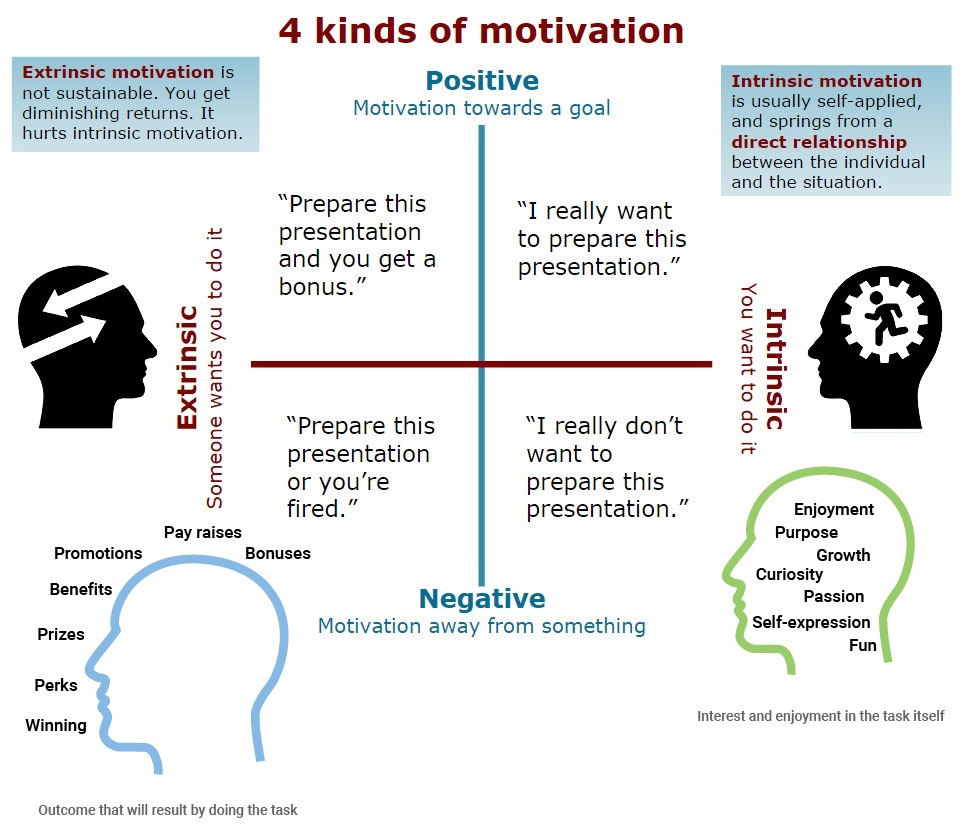

Once the stage is set, and we have created the most productive and positive work environment we can, we need to understand employee motivation, both extrinsic and intrinsic.

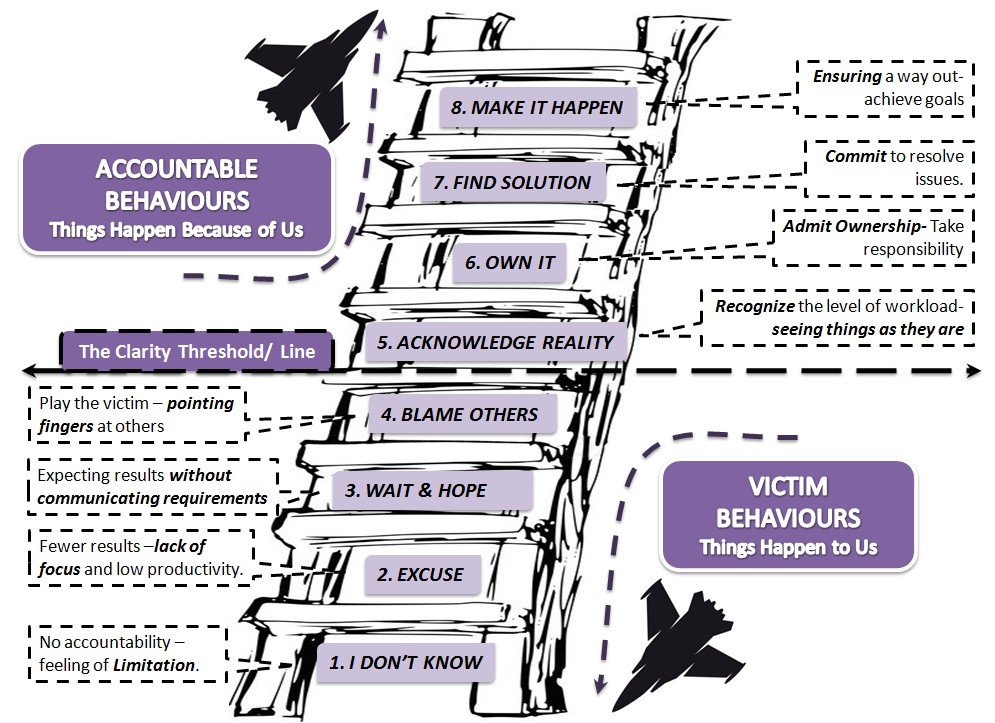

The Accountability Ladder

The accountability ladder could be described in eight steps broken in two groups; accountable or victim behaviors. These are:

- I don’t know: No accountability – management and workforce has no clue about unhappy customers or loss.

- Excuse: More excuses and fewer results – It is mainly due to lack of focus and low productivity.

- Wait and hope: Expecting results without communicating requirements

- Blame others: Blame game – play the victim and find someone or something for cause of failure.

- Acknowledge reality: Recognize the level of workload or tasks required for business growth.

- Own it: Take responsibility and commit to business goals.

- Find solution: Take ownership of situation and ability to handle issues professionally.

- Make it happen: Develop innovative products and achieve breakthrough goals.

The Line between Victimization & Accountability

The roots of victimization stems from its subtle system of belief that people cannot become what they desire to become because of their circumstance. People and organizations find themselves thinking and behaving below the line whenever they consciously or unconsciously avoid accountability for individual or collective results. Stuck in these victim behaviors, they begin to lose their spirit and will, until, eventually, they feel completely powerless.

Only by moving above the line and climbing the steps to accountability can we become powerful again. Rather than face reality, sufferers of this malady oftentimes begin ignoring or pretending not to know about their accountability, denying their responsibility, blaming others for their predicament, citing confusion as a reason for inaction, asking others to tell them what to do, claiming that they cannot do it, or just waiting to see if the situation will miraculously resolve itself.

Accountability for results rests at the very core of the total quality, people engagement and empowerment, and continuous improvement. The essence of it therefore is getting people to become personally accountable – rising above their circumstances and doing whatever it takes (within the bounds of ethical behavior) to get the results they want.

Neither individuals nor organizations can stay on the line between these two realms because events will inexorably push them in one direction or the other. While both people and organizations can have accountability in some situations and victim behavior in others, some issue or circumstance will arise to influence them to think and act from either an above the line or below the line perspective. Even the strongest commitment to accountability will not prevent us from ever falling below the line. That sort of perfection is not humanly possible. But those who are truly accountable never remain there for long.

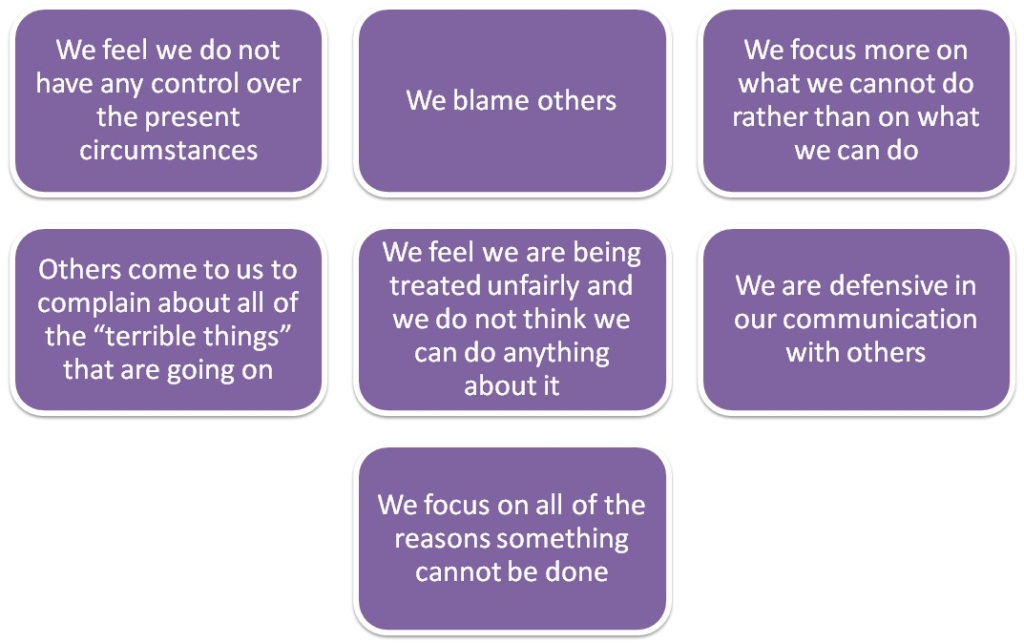

Where Are We:

We can take a moment to identify where we are on this ladder. Here are a few pointers that may help:

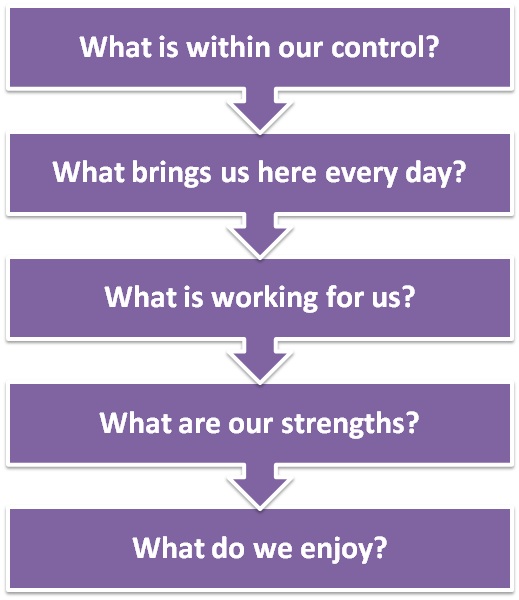

Moving Up the Ladder – So how do we get others or ourselves above the line? Take a few moments to answer the following questions:

What did we notice about these questions? They are all positively focused. Spending the time to answer them may give us a new perspective or place to focus our emotional energy. These are also great questions to ask our people if we feel they are struggling below the line. Questions like these can really open up discussion and help someone refocus.

All of us have been below the line. All of us know what it is like to feel as if we are being treated unfairly and are trapped in our current circumstances. The Accountability Ladder is a great way to diagnose where we are. The ability to understand and help individuals work through the reasoning of why living “Below the Line” can cause undue stress and overall misery; can help them move to a position that may be healthier and happier in the long run.

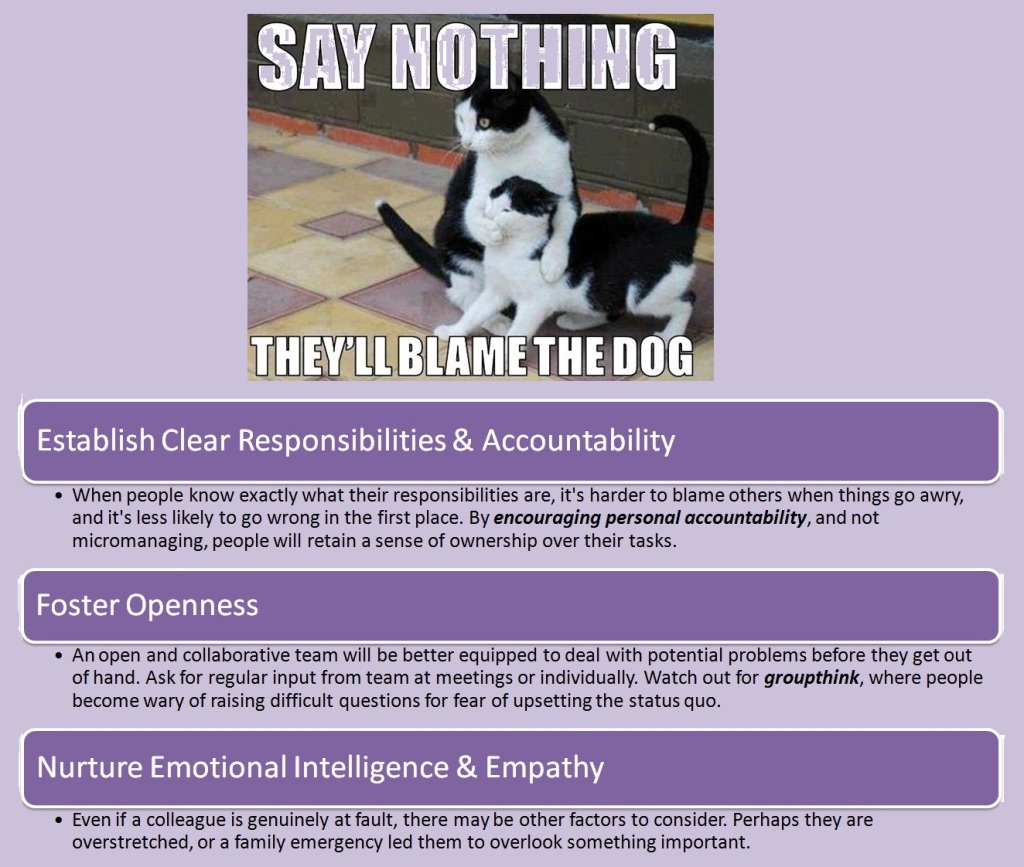

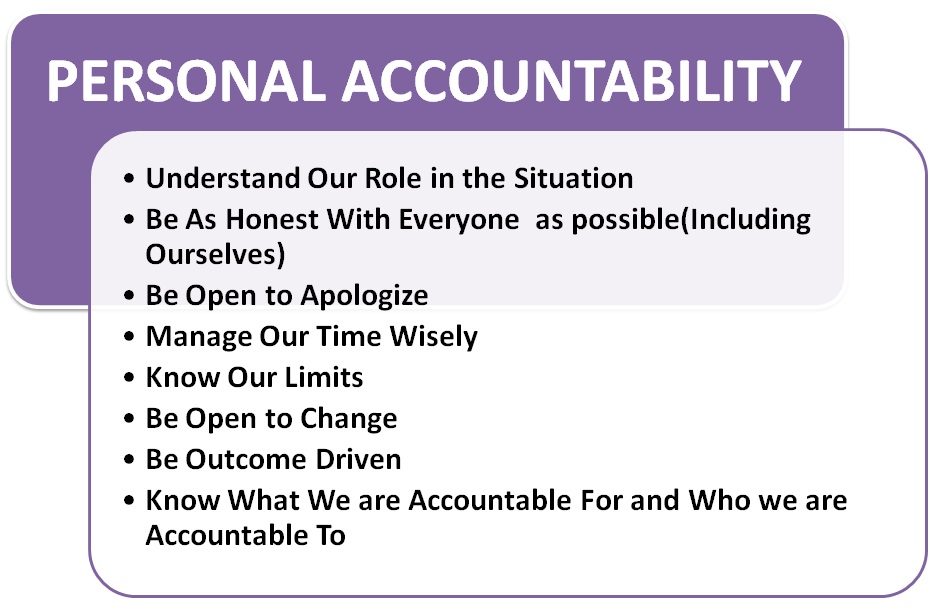

Ways to Imbibe Personal Accountability

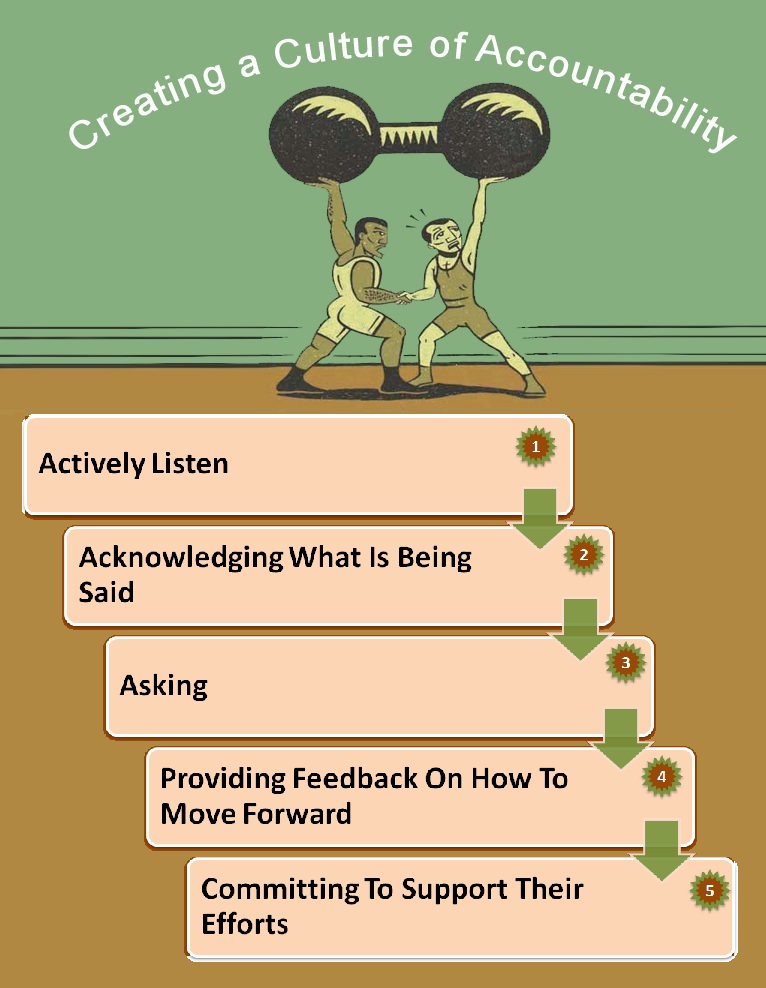

Guiding People to get them Above the Line:

There are five steps to follow when guiding others above the line. These include:

The most critical piece of this is number three. After we have spent time listening and acknowledging the current challenges, the question we need to ask them is, “Given our current circumstances, what else can we do to move forward?” This helps shift them from victim mode to action. Once they begin to talk about what else can be done, make sure to provide the feedback and the support they need to move ahead.

Content Curated By: Dr Shoury Kuttappa