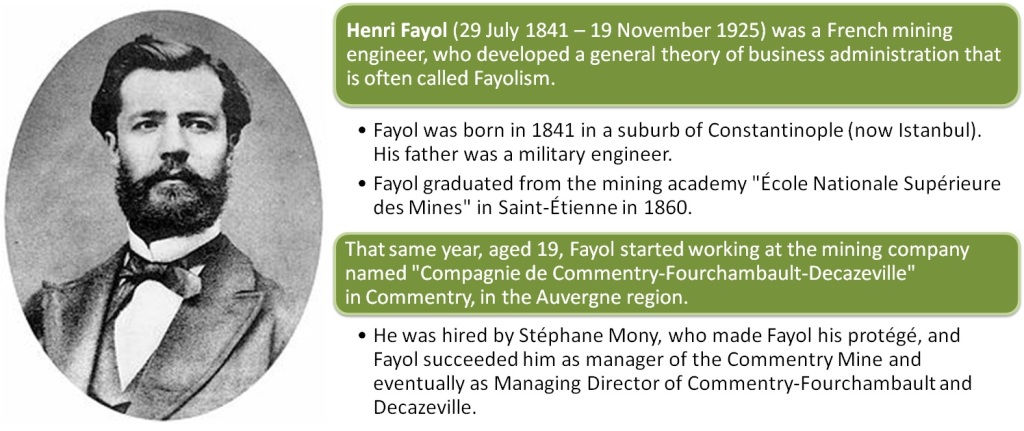

As our career progresses, we may find we do fewer technical tasks and spend more time guiding a team or planning strategy. While that’s often a given today, in the 19th century most companies promoted the best technicians. But Henri Fayol recognized that the skills that made them good at their jobs did not necessarily make them good managers.

Who Was Henri Fayol?

Fayol’s 14 Principles of Management identified the skills that were needed to manage well. While inspiring much of today’s management theory, they offer tips that we can still implement in our lives and organizations. Fayol also created a list of the five Primary Functions of Management, which go hand in hand with the Principles.

What Is Administrative Theory?

Fayol called managerial skills “administrative functions.” In his 1916 book, “Administration Industrielle et Générale,” he shared his experiences of managing a workforce. Fayol’s book – and his 14 Principles of Management – helped to form what became known as Administrative Theory. It looks at the organization from the top down, and sets out steps for managers to get the best from employees and to run a business efficiently.

Caveat: . . . . . . . . . . Administrative Theory is characterized by people “on the ground” who share personal experiences, improve practices, and help others to run an organization. This contrasts with the Scientific Management Ideas led by Frederick Taylor , which experimented with how individuals work to boost productivity.

The 14 Principles of Management: A Revisit

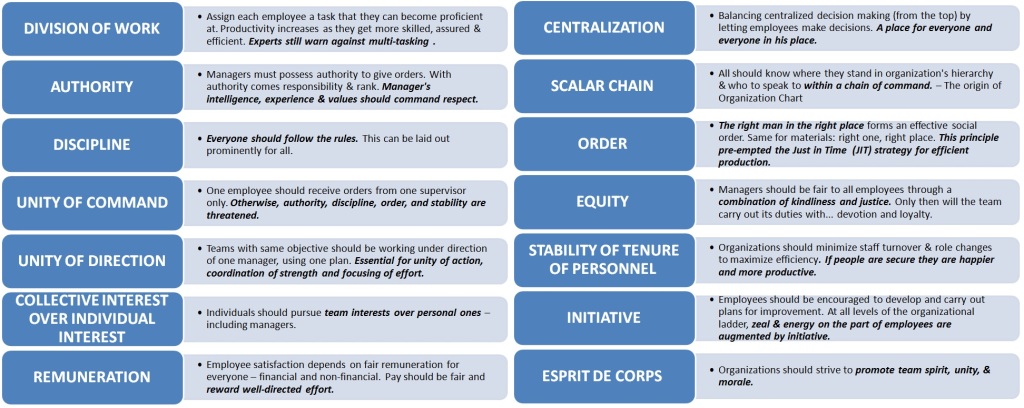

By focusing on administrative over technical skills, the Principles are some of the earliest examples of treating management as a profession. They are:

What are Fayol’s Five Functions of Management?

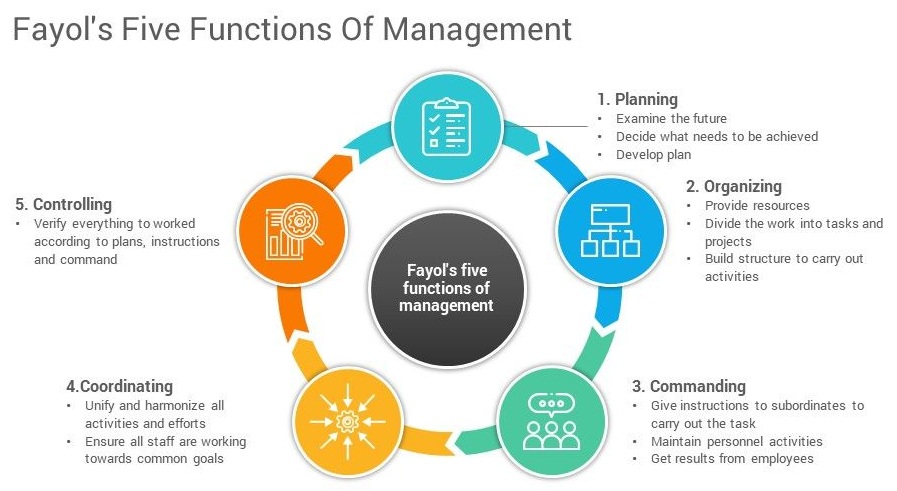

While Fayol’s 14 Principles look at the detail of day-to-day management, his Five Functions of Management provide the big picture of how managers should spend their time. They are:

Is Fayolism Still Relevant Today?

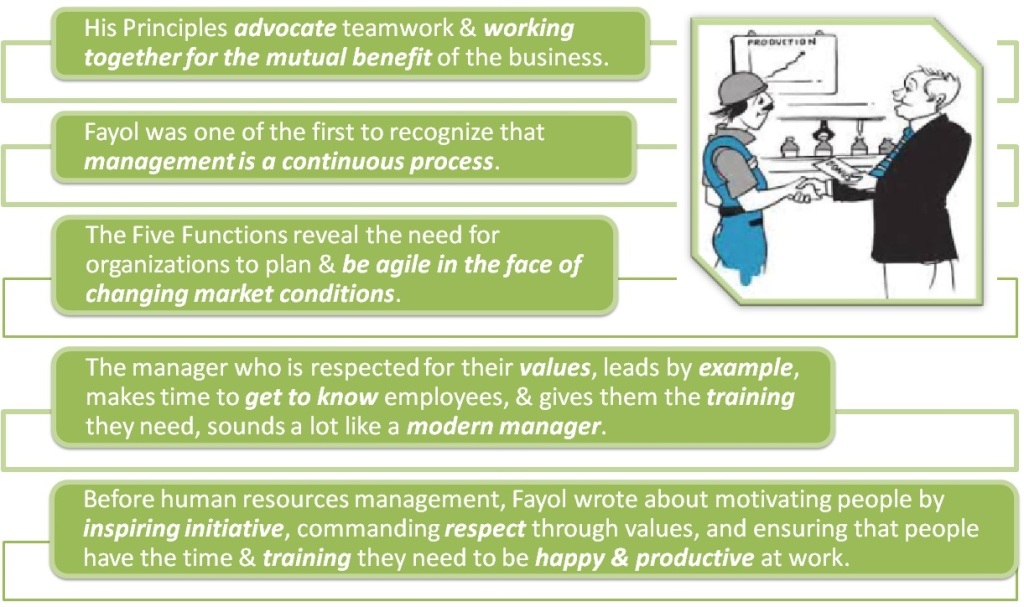

Fayol highlighted the differences between managerial and technical skills. What’s more, he was one of the first to recognize that “manager” is a profession – one whose skills need to be researched, taught and developed. We only have to look at the language he used to see that Fayol was writing over 100 years ago. For example, he refers to employees as “men.”

But, without the contributions of these pioneers, such as Fayol, we would probably be teaching industrial engineering, sociology, economics, or perhaps ergonomics to those who aspire to manage. To be doing so would push us back to the 19th century, when technical know-how reigned supreme as a path to managerial responsibility. When we look closer, we discover that many of Fayol’s points are fresh and relevant. Such as:

Some of these ideas may seem a bit obvious, but at the time they were ground breaking. And the fact that they’ve stuck shows just how well Fayol’s Principles work.

Criticism Of Fayol’s Principles Of Management

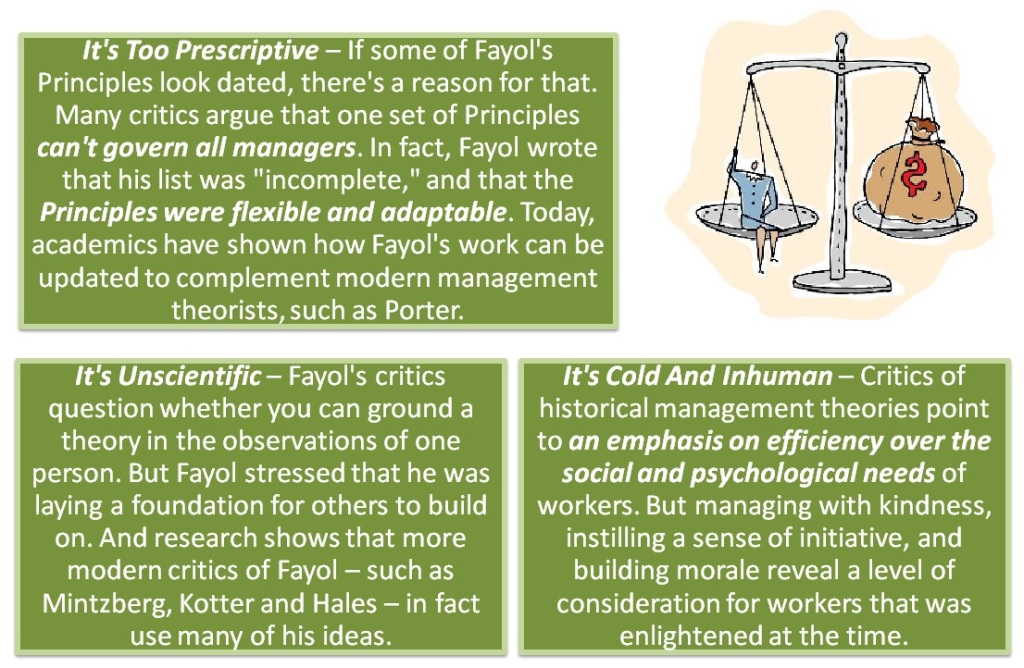

That’s not to say that everyone is a fan of Fayol’s Administrative Theory. Some detractors claim that:

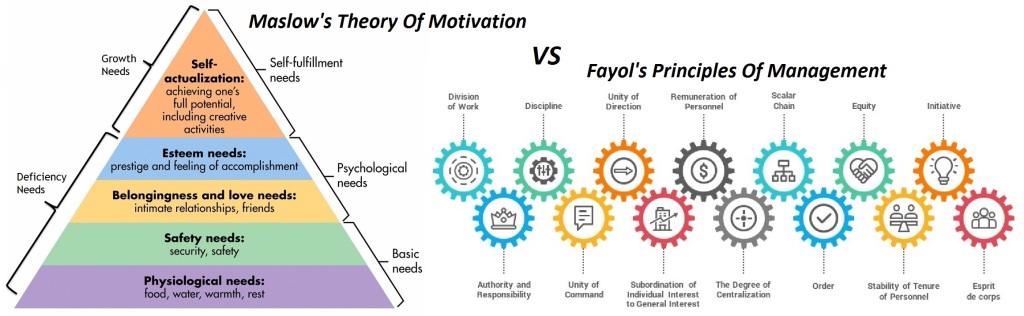

The Interlinks Between the Theories Of Henry Fayol & Abraham Maslow

Fayol’s perspective of the overall success of an organization was to include the formulation of goals, strategies and plans and to work through others to ensure that these activities were implement. These principles also had to be supplemented and supported by discipline and anticipation. Fayol also believed that management could be taught and was concerned about improving the quality of management.

Maslow’s theory of motivation, on the other hand, took a more psychological approach, which focused on employee motivation. This theory proposed that within every person lied a hierarchy of five needs – starting with physiological needs and ascending to safety, social, esteem and finally, self-actualization needs. Hence, in order to motivate a person, Maslow stated that lowest level needs must be substantially satisfied before the next level can be activated and so on.

Application of Fayol’s Concepts

Fayol believed that the responsibility of general management is to lead the enterprise toward its objective by making effective and efficient use of available resources.

Fayol’s five functions are the rules of his administrative doctrine. He had shown sustained effort that his administrative principles could be applied to all social organizations from the family to the state. He stressed that the 14 principles must be flexible and adaptable to the situation at hand. The principles of management were aimed at helping managers manage more effectively.

Application of Maslow’s Concepts

In Maslow’s theory, it is assumed that when an individual has the knowledge and skills to perform his or her job, a manager can influence their motivation to achieve levels of excellence. Maslow’s five needs are arranged in a hierarchy of importance that can be described as prepotency. The higher-level needs are not important and will not manifest till lower-needs are met and satisfied. This hierarchy can also be divided into two orders of needs. The lower-order needs are physiological, safety and social concerns, and the higher-order needs are esteem and self-actualization concerns.

Comparisons

Fayol’s ideas of the five functions and 14 principles are good frameworks for managers to follow if they want to manage more efficiently and effectively. Maslow’s ideas on how an individual behaves in a working environment has helped us understand the importance of motivation complementing administration from a managerial point of view. These two concepts complement each other as they help managers better manage administratively and psychologically. It depicted how effectively and efficiently a workplace should function and how employees should be motivated to commit and perform at their best. Hence, Fayol and Maslow’s ideas and concepts have indeed helped us understand the job of getting things done through people.

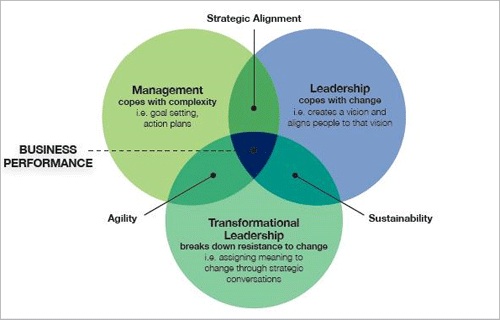

The Interlinks: Management, Leadership And Transformational Leadership

Management is about the mind. It is the manager’s job to stay focused on the task and goals, to set action plans, thereby helping followers deal with complexity. Leadership is more about the heart, or staying focused on the people and their individual characteristics, creating a shared vision that helps followers to participate in a change process. Transformational leadership is about breaking down resistance to change. This is done both through “assigning meaning to change” and through the change within the leader (him)/(her)self.

Content Curated By: Dr Shoury Kuttappa