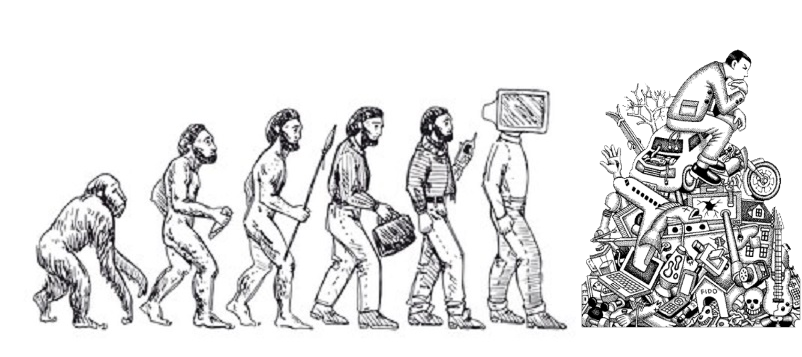

The famous French philosopher Denis Diderot lived nearly his entire life in poverty, but that all changed in 1765. Diderot was 52 years old and his daughter was about to be married, but he could not afford to provide a dowry. Despite his lack of wealth, Diderot’s name was well-known because he was the co-founder and writer of Encyclopédie, one of the most comprehensive encyclopedias of the time.

When Catherine the Great, the Empress of Russia, heard of Diderot’s financial troubles she offered to buy his library from him for £1000 GBP (in AD 1765….!!) Suddenly, Diderot had money to spare. Shortly after this lucky sale, Diderot acquired a new scarlet robe. That’s when everything went wrong.

The Diderot Effect

Diderot’s scarlet robe was so beautiful, that he immediately noticed how out of place it seemed when surrounded by the rest of his common possessions. In his words, there was “no more coordination, no more unity, no more beauty” between his robe and the rest of his items. The philosopher soon felt the urge to buy some new things to match the beauty of his robe. He replaced his old rug with a new one from Damascus. He decorated his home with beautiful sculptures and a better kitchen table. He bought a new mirror to place above the mantle and his “straw chair was relegated to the antechamber by a leather chair.”

These reactive purchases have become known as the Diderot Effect, which states that obtaining a new possession often creates a spiral of consumption which leads us to acquire more new things. As a result, we end up buying things that our previous selves never needed to feel happy or fulfilled.

Why We Want Things We Don’t Need

We can spot similar behaviours in many other areas of life. Some common instances are:

Life has a natural tendency to become filled with more. We are rarely looking to downgrade, to simplify, to eliminate, to reduce. Our natural inclination is always to accumulate, to add, to upgrade, and to build upon.

The Role Of The Diderot Effect In Evolution

Now it may seem from the get-go that the Diderot Effect feeds on something negative, and the words greed and consumerism come to mind. But when we think about it, the Diderot Effect could be a form of evolution. After all, as the world progresses towards a new chapter, everyone in it would also evolve in terms of their needs and wants.

For example, decades ago, one would not think about having the ability to talk to someone from the other side of the world on a real-time basis, and never at a low cost. However, smartphones, mobile gadgets and the internet has made all this possible. Now, these are not just considered as wants, but actual needs. And with these needs comes a string of other needs, like the subscription to a data plan. For business owners, this effect causes you to think about two things:

- The consumer’s need for upgrades

- The consumer’s need for accessories and/or complementary products

The Diderot Effect in Action

Here’s a clear example of how this works. Let’s look at a professional on the go. This person probably has a laptop that he/ she uses to communicate with the team and prepare presentations and reports as the person flies from one site to another. If we are in the business of developing software for this professional, how would we take advantage of the situation?

Well, we would probably make sure that the tools the person uses continue to be as efficient as possible. For every challenge or difficulty these professionals encounter, we can have a ready upgrade that would solve the problem in an instant. However, these upgrades would require other peripherals as well, sometimes, reaching a point where the person using it has to upgrade their laptop’s operating system, or buy a new and more advanced laptop.

It is the same scenario as your basic Diderot Effect – but with an underlying reason that justifies the process. It’s not just about a senseless yearning for exquisite things for the want of upgrading one’s lifestyle. It’s also about keeping up with the times and understanding that as the world evolves, our needs would have to evolve as well for us to continue being productive and successful.

Mastering the Diderot Effect

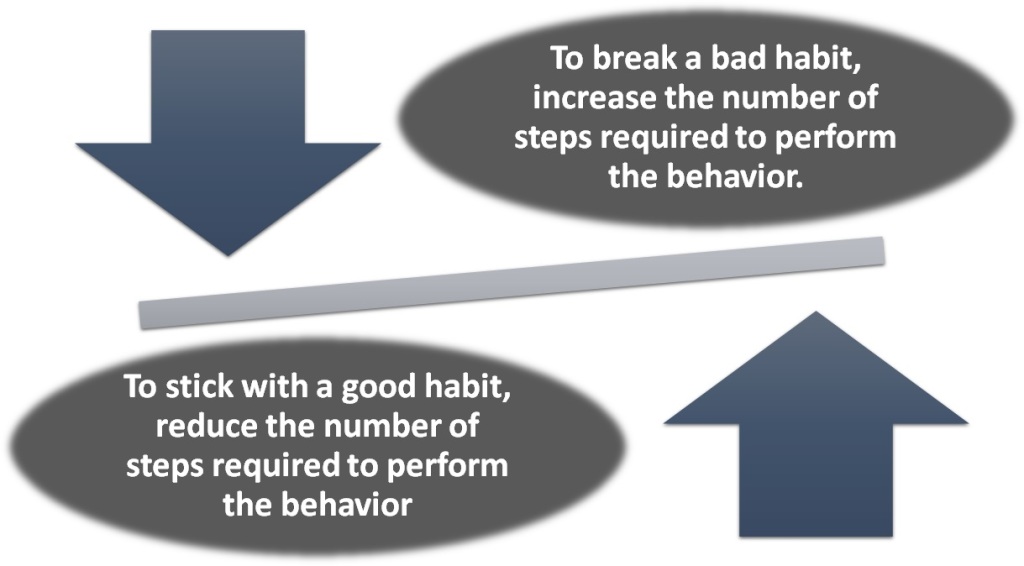

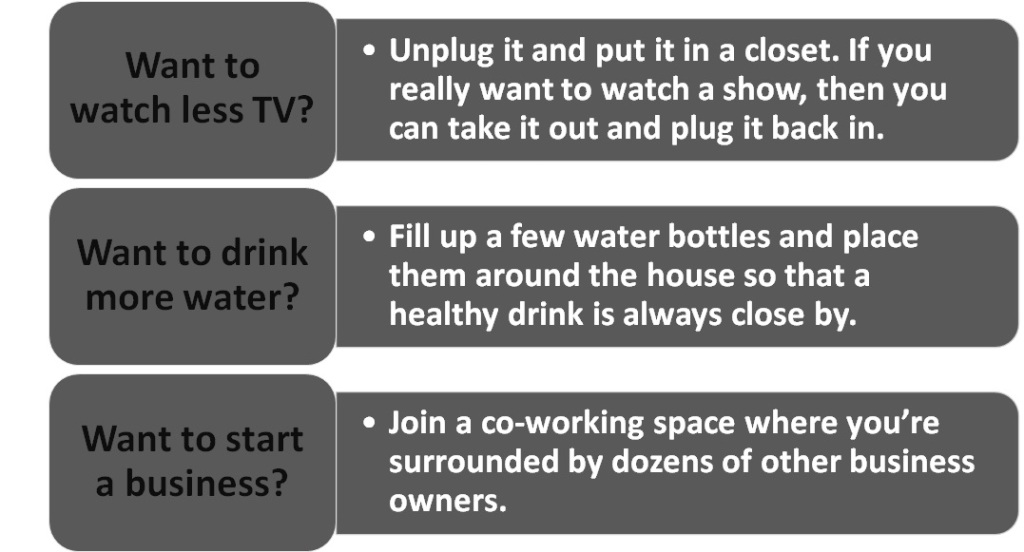

The Diderot Effect tells us that life is only going to have more things fighting to get in it, so we need to understand how to curate, eliminate, and focus on the things that matter. Nearly every habit is initiated by a trigger or cue. One of the quickest ways to reduce the power of the Diderot Effect is to avoid the habit triggers that cause it in the first place. Unsubscribe from commercial emails. Call the magazines that send catalogues and opt out of their mailings. Meet friends at the park rather than the mall. Block favourite shopping websites using tools like Freedom.

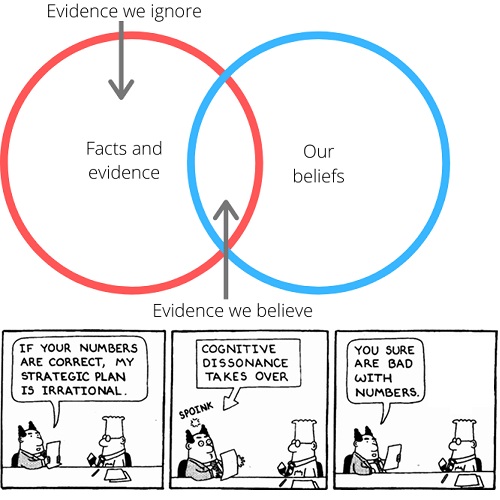

Become aware it is happening. Observe when we are being drawn into spiralling consumption not because of an actual need of an item, but only because something new has been introduced. Analyse and predict the full cost of future purchases. A store may be having a great sale on a new outfit—but if the new outfit compels us to buy a new pair of shoes or handbag to match, it just became a more expensive purchase than originally assumed.

Buy items that fit our current system. We don’t have to start from scratch each time we buy something new. When we purchase new clothes, we can look for items that work well with our current wardrobe. When upgrading to new electronics, we can get things that play nicely with our current pieces so we can avoid buying new chargers, adapters, or cables.

Buy One, Give One. Each time we make a new purchase, we can give something away. Get a new TV? Give the old one away rather than moving it to another room. The idea is to prevent the number of items from growing. The habit of always be curating our life to include only the things that bring us joy and happiness can be effective.

Let go of wanting things. There will never be a level where we will be done wanting things. There is always something to upgrade to. Get a new Honda? You can upgrade to a Mercedes. Get a new Mercedes? You can upgrade to a Bentley. Get a new Bentley? You can upgrade to a Ferrari. Get a new Ferrari? Have you thought about buying a private plane? We need to realize that wanting is just an option our mind provides, not an order we have to follow.

Our natural tendency is to consume more, not less. Taking active steps to reduce the flow of unquestioned consumption makes our lives better.

Setting self-imposed limits helps as well. Live a carefully constrained life by creating limitations for you to operate within. Avoid unnecessary new purchases. Realize the Diderot Effect is a significant force and overcoming it is very difficult. There are times when we have a legitimate need to buy new things. But the best way to overcome the Diderot Effect is to never allow it to overpower us in the first place.

Remind ourselves that possessions do not define us. The abundance of life is not found in the things that we own. Our possessions do not define us or our success. Buy things for their usefulness rather than their status. Stop trying to impress others with our stuff and start trying to impress them with our life.

***Source Credits: http://www.en.wikipedia.org

Content Curated By: Dr Shoury Kuttappa