A brief story:

In the summer of 1830, Victor Hugo was facing an impossible deadline. Twelve months earlier, the French author had promised his publisher a new book. But instead of writing, he spent that year pursuing other projects, entertaining guests, and delaying his work. Frustrated, Hugo’s publisher responded by setting a deadline less than six months away. The book had to be finished by February 1831.

Hugo concocted a strange plan to beat his procrastination. He collected all his clothes and asked an assistant to lock them away in a large chest. He was left with nothing to wear except a large shawl. Lacking any suitable clothing to go outdoors, he remained in his study and wrote furiously during the fall and winter of 1830. The Hunchback of Notre Dame was published two weeks early on January 14, 1831.

Procrastination is usually a “yes” or “no” question”

For more conventional instances, consider addictive behaviour patterns or compulsive traits like over-shopping and blowing the budget, or manic media use; maybe even something like starting an argument one “knows” one will regret and that will lead to trouble or grief.

Having an explanation seems good because it suggests some kind of intervention based on that knowledge, but in some cases, it just doesn’t work. Yet we still feel the hypnotic pull toward explanations, even if the terms being explained are just accepted in a very uncritical way.

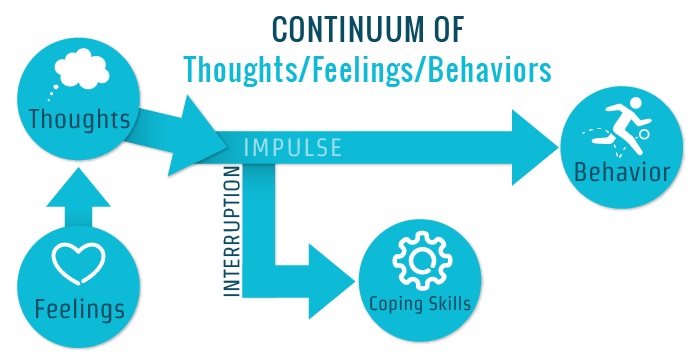

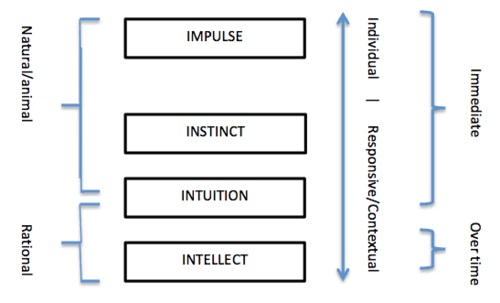

When we make a decision to do something or not, our brain usually has a “gut instinct” answer of yes or no, before the words even come out of the mouth. We consider what benefit it has first, and then what benefit it may have for another person. Then we consider other criteria like time, strength, and effort it will take before we actually decide what it is we are going to do. This all happens in a split second before we commit, and the answer comes out of the mouth.

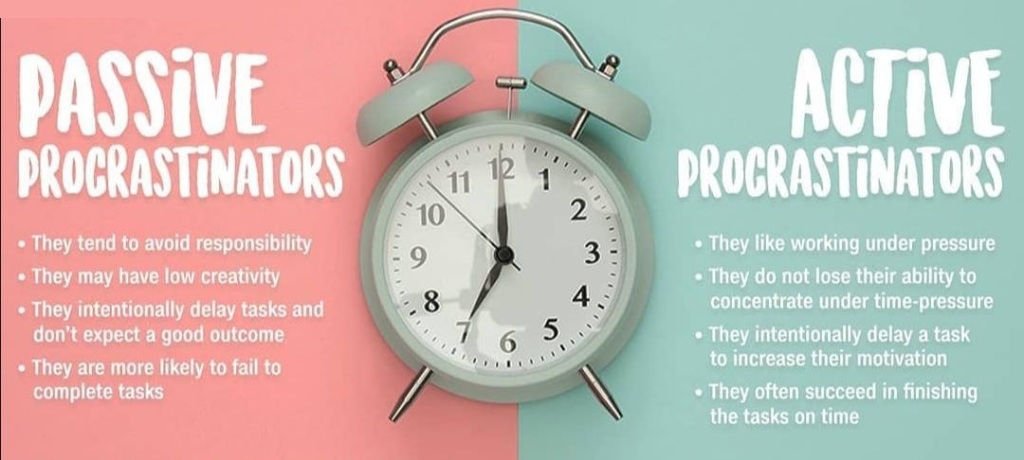

Often, procrastination occurs when you have decided to complete a task, but you keep postponing until later without consciously choosing to do it then. Not all procrastination is bad procrastination. There are two types of procrastinators- active and passive.

Though you may be convinced by this that you are an active procrastinator the truth is most of us are actually passive procrastinators. We delay our work just because we can and with no justifiable reason.

Maybe it is better to try to “own” the behavior rather than blaming externals. So, it is not necessarily a useless idea. The concept of Akrasia is a sort of promise the executive self makes to itself about self-control and autonomy. And it is also the basis for promises one makes to other people about accountability, or rather, explanations for the occasional breakdown and exception.

The Ancient Problem of Akrasia

Human beings have been procrastinating for centuries. Even prolific artists like Victor Hugo are not immune to the distractions of daily life. The problem is so timeless, in fact, that ancient Greek philosophers like Socrates and Aristotle developed a word to describe this type of behavior: Akrasia.

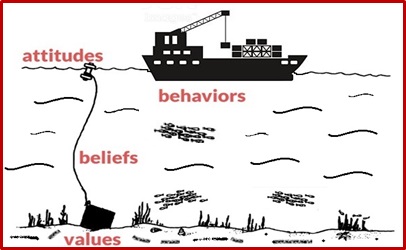

Human behaviour is complex, and we interpret through a network of concepts which themselves are cultural and philosophical constructs. If the typical definition of “akrasia” is “weakness of will”, then what is will? If will is some vaguely defined power of “mind”, then what is mind? If mind is an active presence within “self”, then what is self? … and so on.

Akrasia is the state of acting against your better judgment. It is when you do one thing even though you know you should do something else. Loosely translated, you could say that akrasia is procrastination or a lack of self-control. Akrasia is what prevents you from following through on what you set out to do. Why would Victor Hugo commit to writing a book and then put it off for over a year? Why do we make plans, set deadlines, and commit to goals, but then fail to follow through on them?

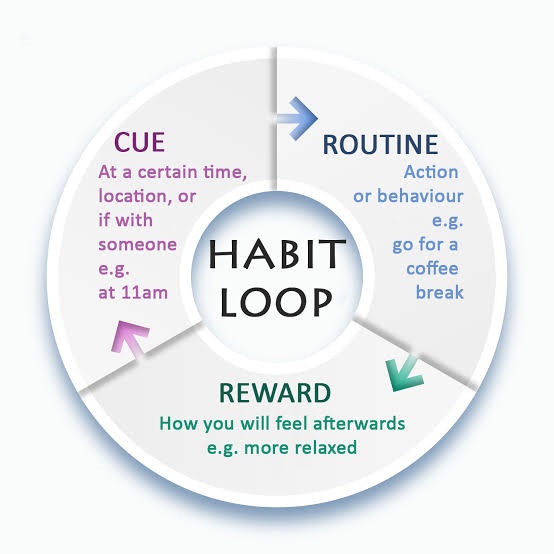

Also, akrasia is loss of self-control, in the sense of action contrary to reason. In akrasia, there is an ingrained habit in an individual, of the non-rational elements of the soul subverting the rational capacities. Action is usually guided in a range of ways by reason. So akrasia is interesting because it involves a departure from a norm.

Why We Make Plans, But Don’t Take Action

One explanation for why akrasia rules our lives and procrastination pulls us in has to do with a behavioural economics term called “time inconsistency.” Time inconsistency refers to the tendency of the human brain to value immediate rewards more highly than future rewards.

When we make plans for ourself — like setting a goal to lose weight or write a book or learn a language — we are actually making plans for our future self. We are envisioning what we want our life to be like in the future and when we think about the future it is easy for our brain to see the value in taking actions with long-term benefits.

When the time comes to make a decision, however, we are no longer making a choice for our future self. Now we are in the moment and our brain is thinking about the present self. And researchers have discovered that the present self really likes instant gratification, not long-term payoff. This is one reason why we might go to bed feeling motivated to make a change in our life, but when we wake up, we find ourselves falling into old patterns. Our brain values long-term benefits when they are in the future, but it values immediate gratification when it comes to the present moment. This is one reason why the ability to delay gratification is such a great predictor of success in life. Understanding how to resist the pull of instant gratification—at least occasionally, if not consistently—can help you bridge the gap between where you are and where you want to be.

A Framework to Beat Procrastination

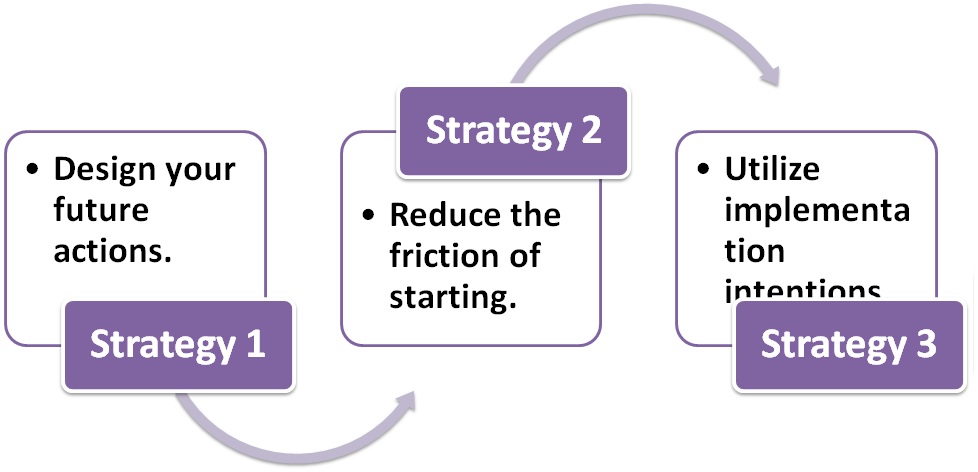

Strategy 1: Design your future actions.

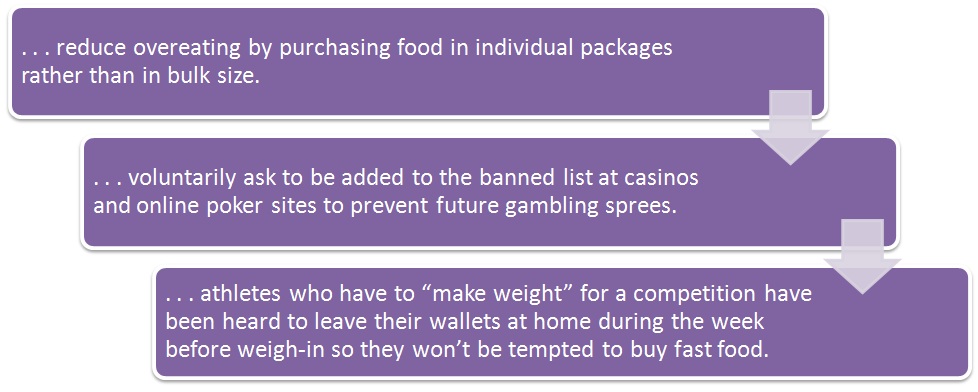

When Victor Hugo locked his clothes away so he could focus on writing, he was creating what psychologists refer to as a “commitment device.” A commitment device is a choice we make in the present that controls our actions in the future. It is a way to lock in future behavior, bind us to good habits, and restrict us from bad ones.

There are many ways to create a commitment device. We can:

The circumstances differ, but the message is the same: commitment devices can help us design our future actions. The goal is to find ways to automate our behaviour beforehand rather than relying on willpower in the moment.

Strategy 2: Reduce the friction of starting.

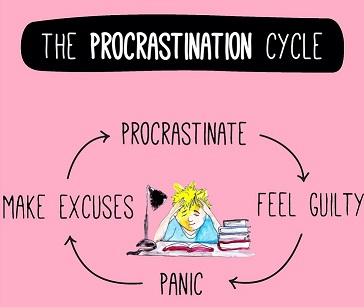

The guilt and frustration of procrastinating is usually worse than the pain of doing the work. In the words of Eliezer Yudkowsky, “On a moment-to-moment basis, being in the middle of doing the work is usually less painful than being in the middle of procrastinating.”

So why do we still procrastinate? Because it is not being in the work that is hard, it’s starting the work. The friction that prevents us from acting is usually centred around starting the behaviour. Once we begin, it is often less painful to do the work. This is why it is often more important to build the habit of getting started when we are beginning a new behaviour than it is to worry about whether or not we are successful at the new habit.

We have to constantly reduce the size of our habits. We need to put all of the effort and energy into building a ritual and make it as easy as possible to get started. We need not worry about the results until the art of showing up is mastered.

Strategy 3: Utilize implementation intentions.

An implementation intention is when we state our intention to implement a particular behavior at a specific time in the future. For example, “I will exercise for at least 30 minutes on [DATE] in [PLACE] at [TIME].” There are hundreds of successful studies showing how implementation intentions positively impact everything from exercise habits to flu shots. It seems simple to say that scheduling things ahead of time can make a difference, but implementation intentions can make us 2x to 3x more likely to perform an action in the future.

Fighting Akrasia

Our brains prefer instant rewards to long-term payoffs. It is simply a consequence of how our minds work. Given this tendency, we often must resort to crazy strategies to get things done—like Victor Hugo locking up all of his clothes so he could write a book. But it is sometimes worth to spend time building these commitment devices if our goals are important to us.

Aristotle coined the term Enkrateia as the antonym of Akrasia. While akrasia refers to our tendency to fall victim to procrastination, Enkrateia means to be “in power over oneself.” Designing your future actions, reducing the friction of starting good behaviors, and using implementation intentions are simple steps that you can take to make it easier to live a life of Enkrateia rather than one of Akrasia.

Content Curated By: Dr Shoury Kuttappa.