We may assume that humans buy products because of what they are, but the truth is that we often buy things because of where they are. For example, items on store shelves that are at eye level tend to be purchased more than items on less visible shelves.

Here’s why this is important – Something has to go on the shelf at eye level. Something must be the default choice. Something must be the option with the most visibility and prominence. This is true not just in stores, but in nearly every area of our lives. There are default choices in our office, car, kitchen and in our living room. If we design for default in our life, rather than accepting whatever is handed to us, then it will be easier to live a better life. In the book Nudge, authors Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein explain a variety of ways that our everyday decisions are shaped by the world around us.

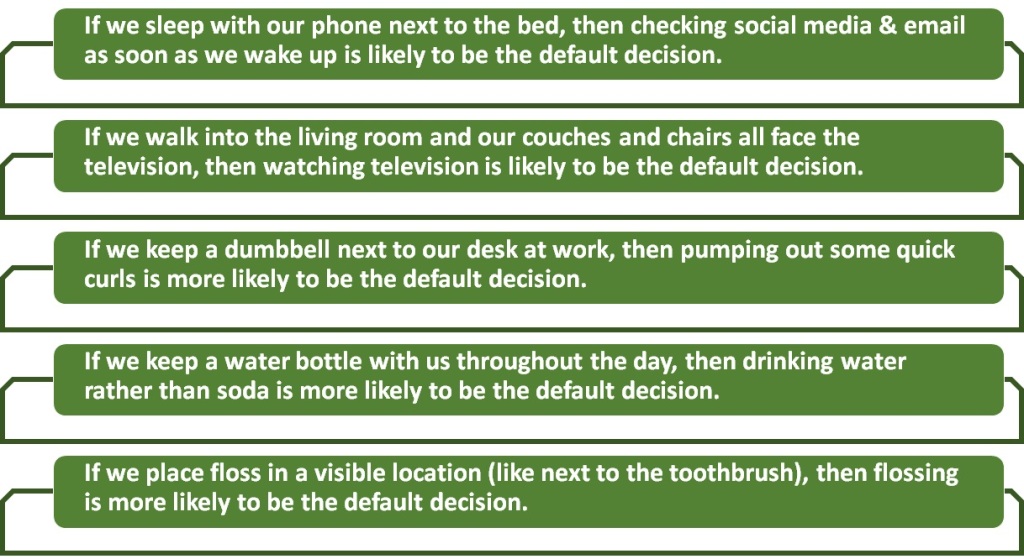

Designing for Default:- . . . Although most of us have the freedom to make a wide range of choices at any given moment, we often make decisions based on the environment we find ourselves in. Consider how our default decisions are designed throughout our personal and professional life. Some examples may be:

Choice Architecture

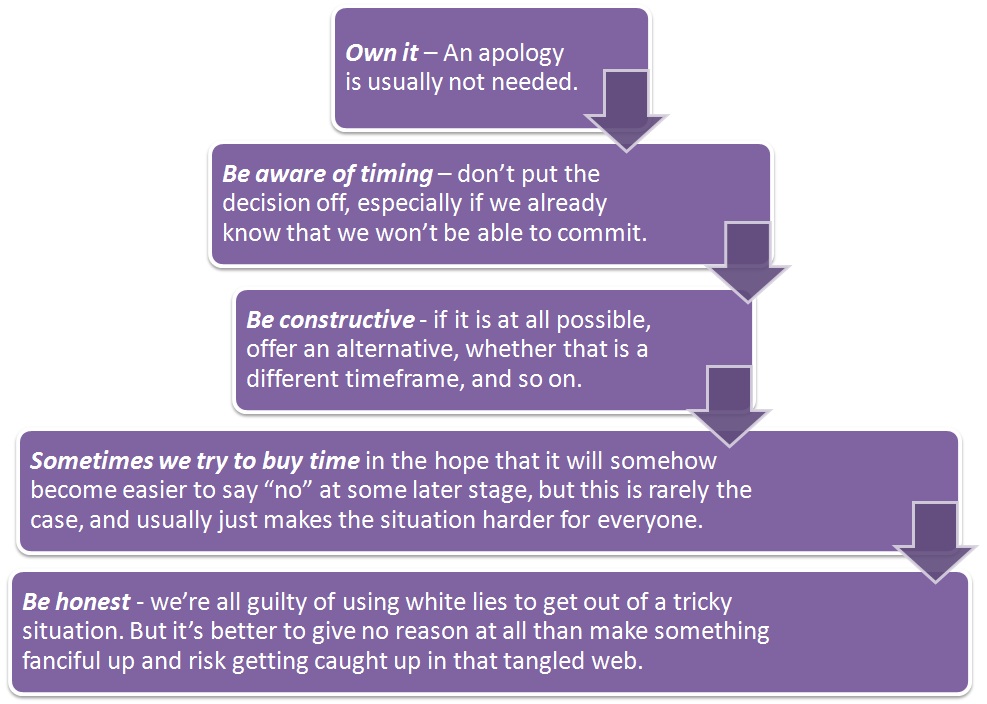

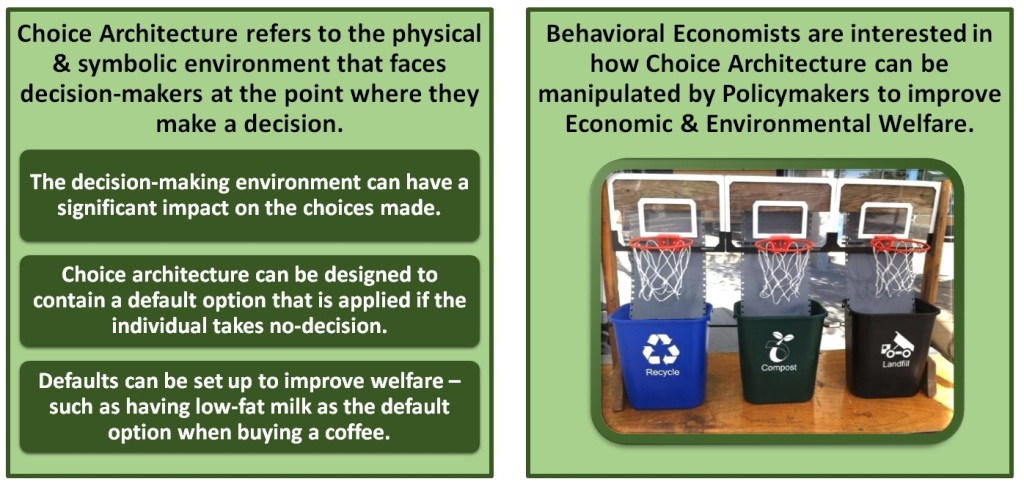

Researchers have referred to the impact that environmental defaults can have on our decision making as choice architecture. Choice architecture is the design of the different ways to present choice options to a chooser. This presentation will influence the final choice made. Lets look at this with a simple dinner party example. Suppose we are invited to a friend’s house for the evening with dinner. As the evening begins, we notice that there is a large bowl of French fries put out before us. We have three choices:

For someone with limited self-control when it comes to food, choice number C is doubtful. Choice number A and B are both plausible as well. As it becomes obvious that the French fries are being consumed in its entirety, the host removes the bowl. With the bowl gone, the guests will maintain a sufficient appetite to enjoy all of the food that will follow. The question is, how could we all possibly be relieved when our choice to eat the fries had been taken away? In the land of economics, it is against the law for us to be happy about this.

If the bowl of fries was left, all of it would have been consumed. When the bowl was taken away, we all sighed in relief over the fact we had no fries to eat. How could we change our mind in the space of say fifteen minutes or so in regards to what we wanted? Our decision was being made in an environment where there are many features – both noticed and unnoticed – influencing our final choice. In this scenario, the host architected the environment, to create new surroundings. With no fries bowl, all decide by default that choice C was the better (and healthier) option.

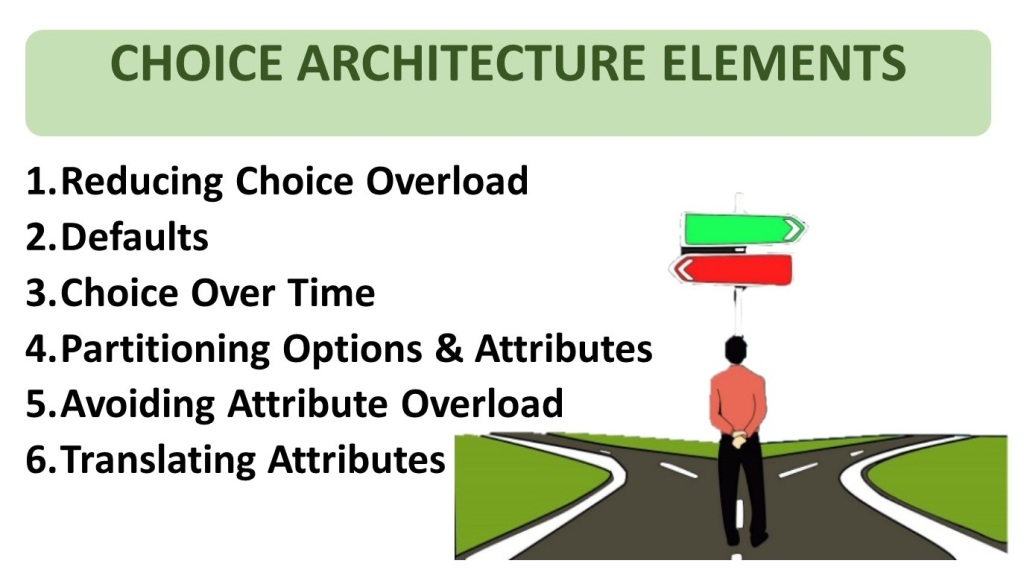

Choice architecture as a concept was born from the discipline of behavioral economics. This discipline shows that individuals tend to be subject to predictable biases. These common and predictable biases are termed as elements. The six choice architecture elements are:

Approaches to Enhance Our Default Decisions

Simplicity. It is hard to focus on the signal when we are constantly surrounded by noise. It is more difficult to focus on reading a blog post when you have 10 tabs open in your browser. It is more difficult to accomplish your most important task when you fall into the myth of multitasking. When in doubt, eliminate options.

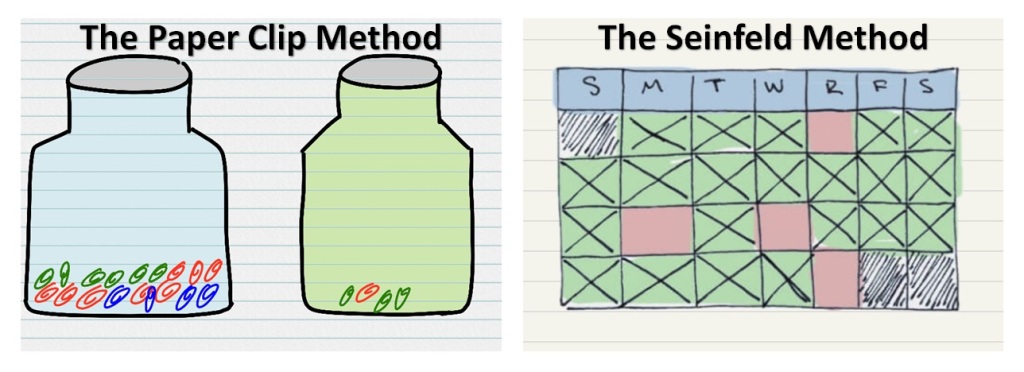

Visual Cues. In the supermarket, placing items on shelves at eye level makes them more visual and more likely to be purchased. Outside of the supermarket, we can use visual cues like the Paper Clip Method or the Seinfeld Strategy to create an environment that visually tracks our actions in the right direction.

Opt-Out vs Opt-In. There is a famous organ donation study that revealed how multiple European countries skyrocketed their organ donation rates: they required citizens to opt-out of donating rather than opt-in to donating. We can do something similar by opting our future self into better habits ahead of time. For example, we could schedule a yoga session for next week while we are feeling motivated today. When the workout rolls around, we have to then justify opting-out rather than motivating ourselves to opt-in.

Designing for default comes down to a very simple premise: shift the environment so that the good behaviors are easier and the bad behaviors are harder.

Fear-Based Decision Making

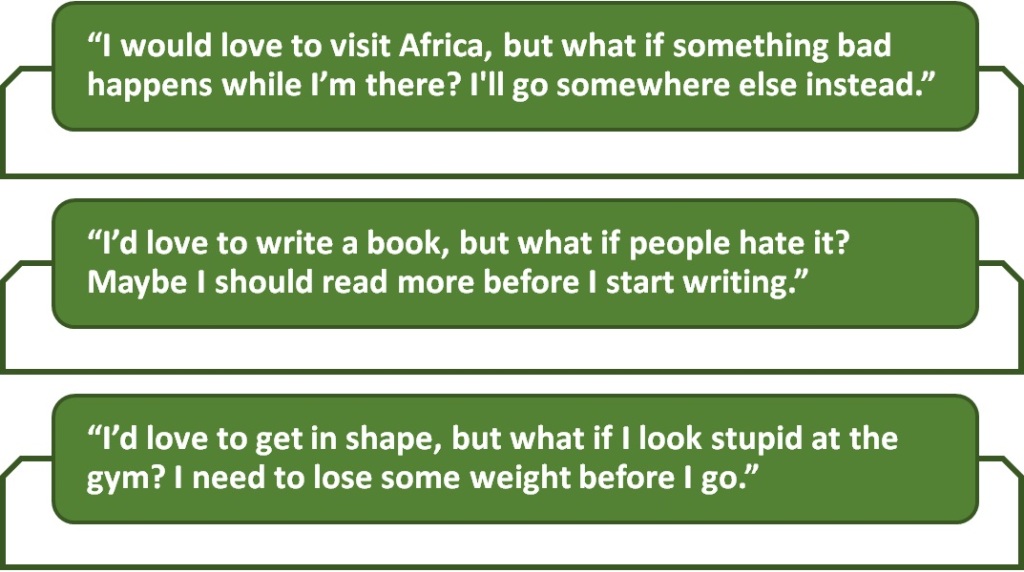

Fear-based decision making is when we let our fears or worries dictate our actions (or our lack of action). Some examples may be:-

Considerations on Overcoming Fear-Based Decisions

Stepping out of the Comfort Zone is important. If we fail inside our comfort zone, it’s not really failure, it’s just maintaining the status quo. If we never feel uncomfortable, then we are never trying anything new.

Also, Just because we don’t like where we have to start from doesn’t mean we should not get started. Feelings of fear and uncertainty have a way of making us feel unprepared. Some instances are:-

Here’s a tough question that forces us to consider the opposite side: How long will we put off what we are capable of doing just to maintain what we are currently doing?

We may need to stop making uncertain things, certain. Just because someone else got rejected from that job doesn’t mean we will too. Maybe we tried to lose weight before, but that doesn’t mean we cannot lose it now.

The More We Limit Ourselves, the More Resourceful We Become

We have a tendency to see boredom as a negative influence and we often use boredom as justification to jump continually from thing to thing. One is weary of living in the country and moves to the city; one is weary of one’s native land and goes abroad; one is weary of Europe and goes to America, etc.

The assumption that often drives these behaviours is that if we want to find happiness and meaning in our lives, then we need more: more opportunity, more wealth, and more things. We start to believe that moving somewhere new will remove the messiness of life. Or, that if we just lived in a new location or had a new job, then we would finally be granted the permission and ability to do the things we always wanted to do. Sometimes the life we are looking for can be found embracing less, not more.

A solitary prisoner for life is extremely resourceful; to him a spider can be a source of great amusement. History is filled with examples of people who embraced their limitations rather than fought them. Ingvar Kamprad only had enough money to start a business selling match sticks. He turned it into IKEA. Richard Branson has built 400 businesses despite having dyslexia. Dhirubhai Ambani began as an errand boy at a petrol bunk. Our limitations can provide us with the greatest opportunity for creativity and inventiveness.

It can be easy to spend our life complaining about the opportunities that are withheld from us and the resources that we need to make our goals a reality. But there is an alternative. We can use these constraints to drive creativity. We can embrace the limitations to foster skill development. The problem is rarely the opportunities we have, but how we use them.

The only thing needed to begin a new life is a new perspective. The more we limit ourselves, the more resourceful we become.

Content Curated By: Dr Shoury Kuttappa