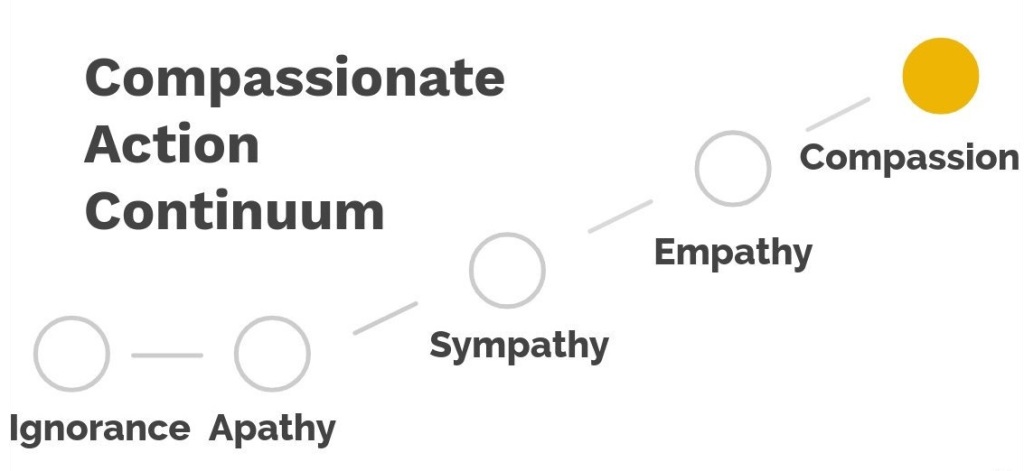

***Continued from Chapter 01 (Covered previously: What is compassion, differentiation from pity, sympathy, empathy, love, etc., Orientations of compassion)

Link to Chapter 01:

How Can We Best Cultivate Compassion?

A growing body of evidence suggests that, at our core, most humans have a natural capacity for compassion. Infants too young to have learned the rules of politeness spontaneously engaged in helpful behaviour without a promise of reward, and would even overcome obstacles to do so. Despite this, everyday stress, social pressures and life experiences, in general, can make it difficult to experience and fully express compassion to ourselves and to others. Fortunately, we also have the capacity to nurture and cultivate a more compassionate outlook.

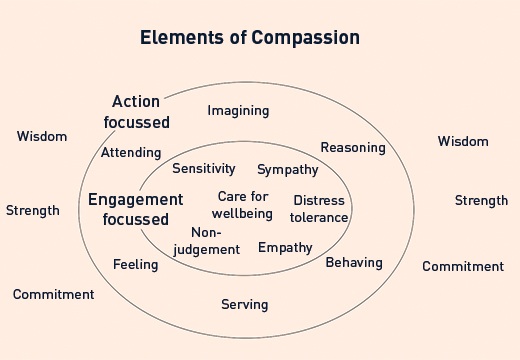

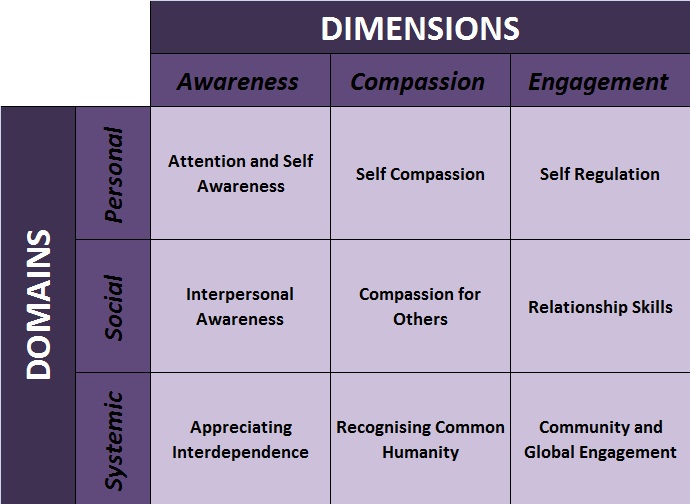

Cultivating compassion is more than experiencing empathy or concern for others. It develops the strength to cope with suffering, to take compassionate action, and the resilience to prevent compassion fatigue – an extreme state of tension and preoccupation with the suffering of others. These qualities support a wide range of goals, from improving personal relationships to making a positive difference in the world.

There are at least six current empirically-supported (Research Based) )interventions that focus on the cultivation of compassion:

A) Compassion-Focused Therapy: . . . . . . . . . . This focuses on two psychologies of compassion. The first is a motivation to engage with suffering, and the second is focused on action, specifically acting to help alleviate and prevent suffering. It is an integrated and multi-modal approach concerned with alleviating the sense of shame and high levels of self-criticism we often experience.

B) Mindful Self-Compassion: . . . . . . . . . . This was developed as a program to help cultivate self-compassion, that is treating ourselves with the same kindness, concern, and support we would show to a good friend. This combines the skills of mindfulness and self-compassion to enhance our capacity for emotional well-being. Its emphasis is on distinguishing between the inner critic and compassionate-self.

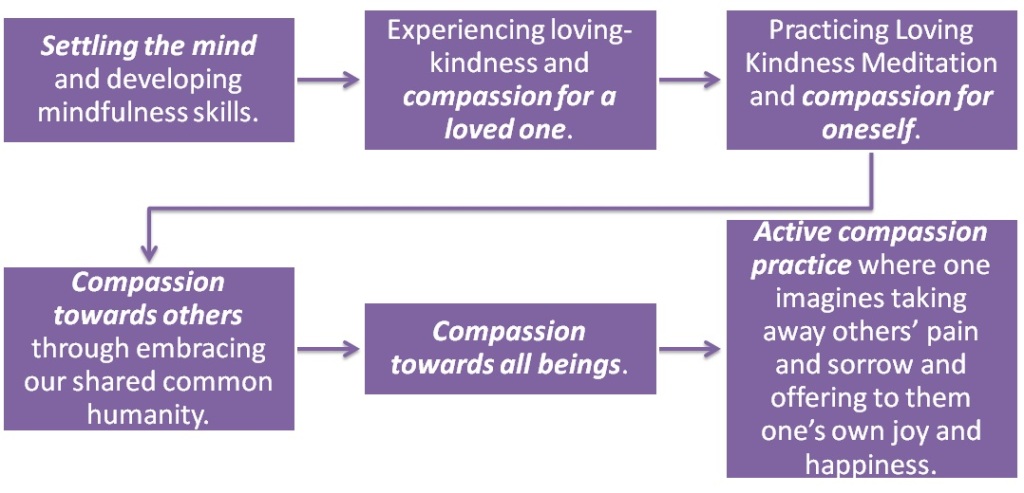

C) Compassion Cultivation Training: . . . . . . . . . . It draws its theoretical underpinnings from contemplative practices of Tibetan Buddhism and Western psychology. It delivers training in compassion practices across six steps:

D) Cognitively-Based Compassion Training: . . . . . . . . . . This draws from what is known as ‘lojong’ in Indo-Tibetan Buddhism and coaches practitioners to cultivate compassion through simple contemplative practices. It incorporates mindfulness and cognitive restructuring strategies to encourage a shift of perspective through reflection about ourselves and our relationship to others.

E) Cultivating Emotional Balance: . . . . . . . . . . This is based on Western scientific research on emotions, and traditional Eastern contemplative practices and is aimed at building emotional balance. Here there is an emphasis on understanding emotions and being able to recognize the emotions of others. It is an educational training method that creates pathways to compassion by training and teaching individuals to recognize the suffering of others and of oneself, and to tolerate the distress more effectively through learning new ways of managing emotions.

F) Compassion Meditations and Loving-Kindness Meditations: . . . . . . . . . .These are often combined and practiced together in compassion-based interventions to help settle the mind, increase compassion to self and others, and to improve mental health. They are meditations during which the aim is to express goodwill, kindness, and warmth towards others by silently repeating a series of mantras. Both practices involve a structured approach where individuals can learn to direct caring feelings towards oneself, then towards loved ones, then towards acquaintances, then towards strangers, then towards someone with whom one experiences interpersonal difficulties, and finally towards all living beings without distinction.

Existing research based popular psychometric instruments (questionnaires) that are used in the measurement of compassion are mentioned below. Each has its own varying validity and focuses on different aspects of compassion.

- Compassionate love scale

- Intended for the general population

- Consists of two forms: one relating to close family and friends, and one focusing on humanity as a whole.

- Santa Clara brief compassion scale

- Examines compassion in relation to strangers

- The compassion scale

- Provides measure of compassion across domains that could be strengthened through guided coaching.

- Self-compassion scale

- Does not include items specifically relating to being attentive to how one is feeling.

- The compassion scale (Pommier)

- Based on the theory compassion consists of kindness, mindfulness, and common humanity.

- Relational compassion scale

- Measures compassion for others, for themselves, their beliefs about how compassionate people are to one another, and their beliefs about how compassionate other people are towards them.

- Compassionate care assessment tool

- This tool is completed by receivers in relation to their caregivers.

- The Schwartz Center compassionate care scale

- Measures receivers’ ratings of compassionate care received from their caregivers.

Ways to Build and Cultivate Compassion in Daily Routines

The aim of these exercises and activities is to cultivate compassion in whatever state you currently occupy.

- Begin each day with compassion in mind

- Volunteer: . . . Donating our time to a worthwhile cause is just one of the ways we can actively show compassion to others.

- Actively listen: . . .Being fully present and truly listening to others. Listening provides relief to those in a world that can be indifferent to suffering.

- Have a self-compassion break – Taking a self-compassion break to help bring the important aspects of compassion to mind when you need it most. Example: Think of a situation that is causing us stress and tell ourselves ‘I am struggling in this moment and that’s ok’, ‘I am not alone’, and offering ourselves soothing words of acceptance.

- Ask ourselves- ‘How would I treat a friend?’ – We are often more critical and judgmental about our own struggles than those of others. How would we treat a friend experiencing hard times? Why treat ourselves any differently?

- Practicing mindfulness – Mindfulness is the process of bringing one’s attention to experiences occurring in the present moment and develops the ability to recognize distress in ourselves while encouraging emotional balance in the face of adversity.

- Keeping a compassion journal –to record the moments we experienced compassion, anything we felt bad about, and anything we judged ourselves harshly for. Write down some kind, understanding words of comfort.

- Commonalities – Rather than focusing on how we differ from others, we can try instead to recognize what we have in common. Reflect on the commonalities we have with everyone else – we are all connected to the larger human experience.

- Guided meditation – Compassion meditation and related practices can have many positive outcomes, including increasing self-compassion and other-focused compassion

- Write a compassion letter to ourselves. Example: Think of something that tends to make us feel bad about ourselves. Now imagine an unconditionally loving and compassionate friend who can see all our strengths and weaknesses. Write a letter to ourself from the perspective of this friend, focusing on the perceived inadequacy we tend to judge ourselves for. What would this friend say from the perspective of unlimited compassion? After writing the letter, put it down for a little while. Then come back to it and read it again, really letting the words sink in.

- The Eastern wisdom practice of Tonglen – take a moment to imagine all the people in the world who may be struggling in the same way that we are. Inhale and think of how we are experiencing the same feelings as others are. Exhale and focus on the compassion we feel both for ourself and for others.

We often consider some people to be more compassionate than others, but we have the potential to adopt a more compassionate outlook through training and deliberate practice. While it may be challenging, the cultivation of compassion is undeniably beneficial – to us and to those around us.

Content Curated By: Dr Shoury Kuttappa.