Most of us can remember playing musical chairs as a child. As the music played and we marched around the circumference of the circle of chairs, we anxiously awaited the music to stop so we could fight for that last seated spot. There was something about that one-on-one physical competition and face-to-face conflict fighting for something tangible that added spice to the game. This is often one of the youngest experiences that we have of a scarcity mentality that can be translated to adult life

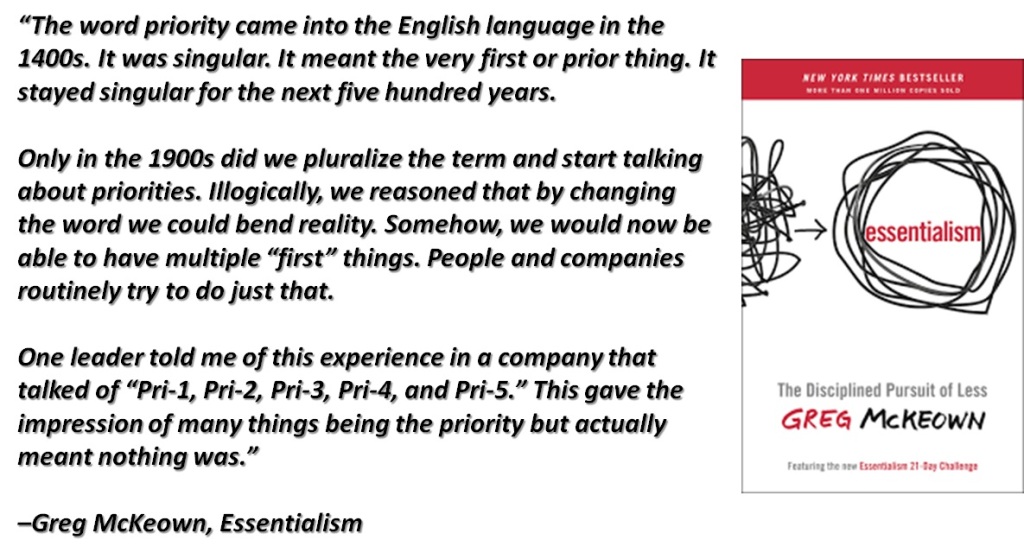

Simply put, Scarcity is the condition of having insufficient resources to cope with demand. When we are faced with limited resources, we strive to make effective use of them in the process of making important decisions. Economics is the study of how we use our limited resources (time, money, etc) to achieve our goals. This definition refers to physical scarcity.

Once we enter that professional world, that “every person for (him/her)self” way of thinking often re-emerges as many people fight for a single job opening or a chance at being promoted. People in the corporate world are conditioned to think in this limiting way, and we may have been influenced as well.

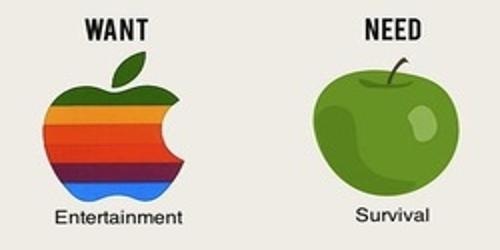

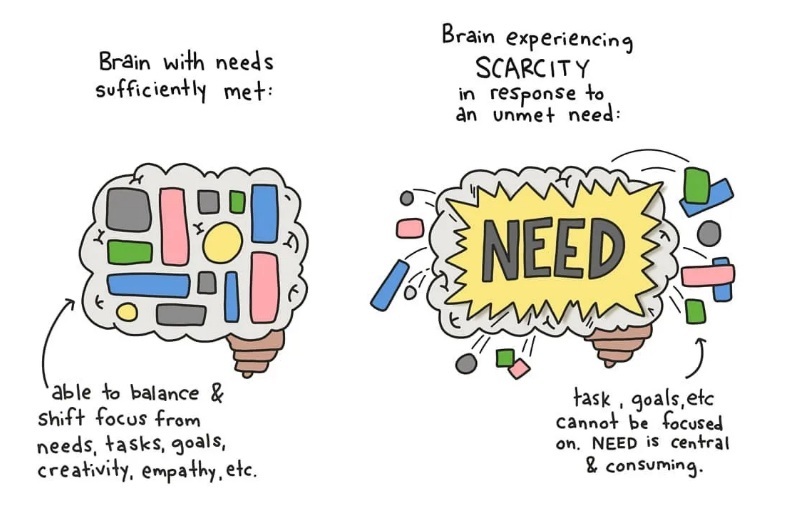

When we think of the word ‘scarcity’, many of us will immediately think about money. After all, it is expensive to live, and many of us concern ourselves by stretching each Rupee. However, scarcity is a mindset. It comes in many other forms – time, relationships, health, intelligence, judgment, willpower, etc. Scarcity orients the mind automatically and powerfully toward unfulfilled needs. For example, food grabs the focus of the hungry. For the lonely person, scarcity may come in poverty of social isolation and a lack of companionship.

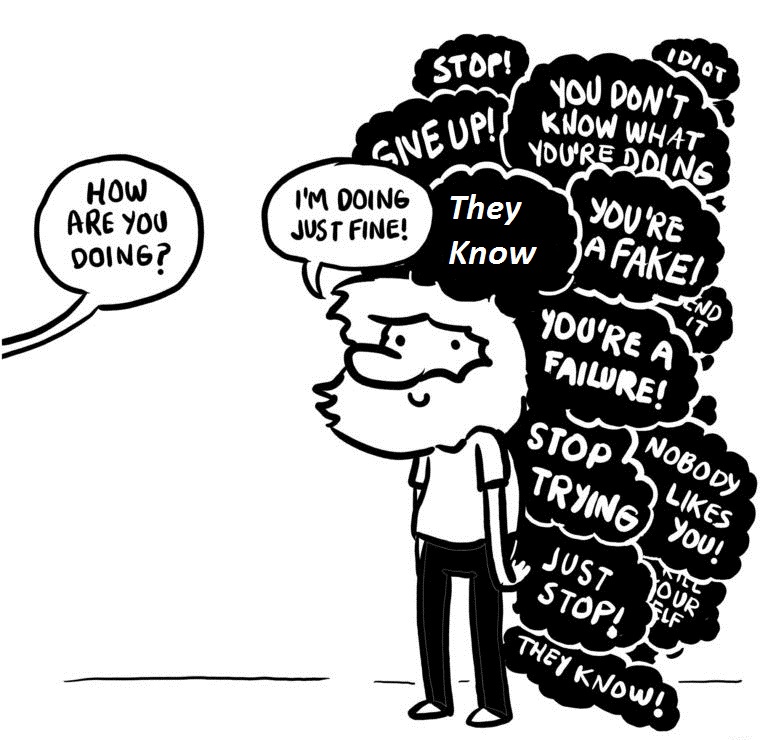

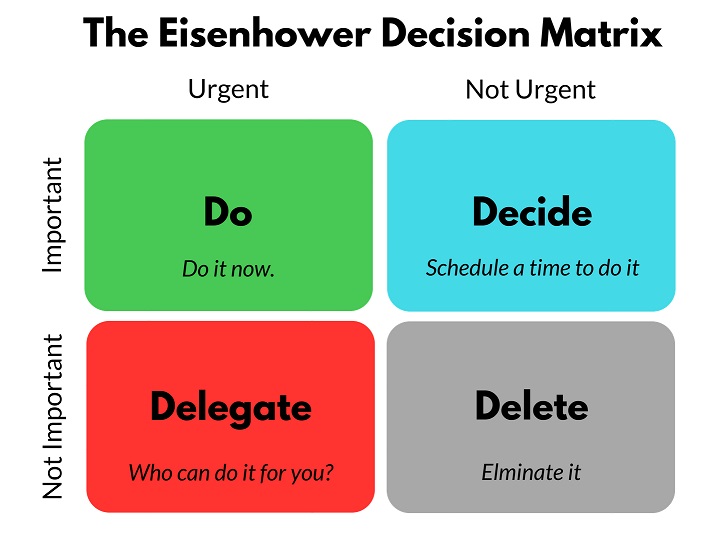

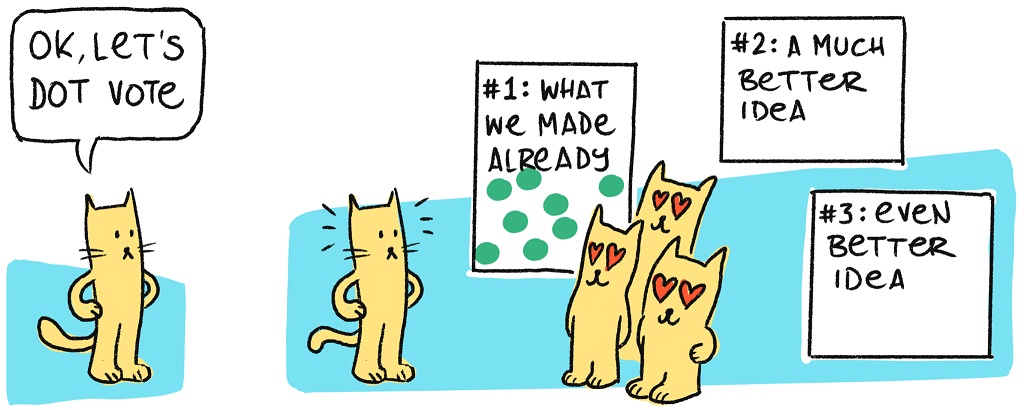

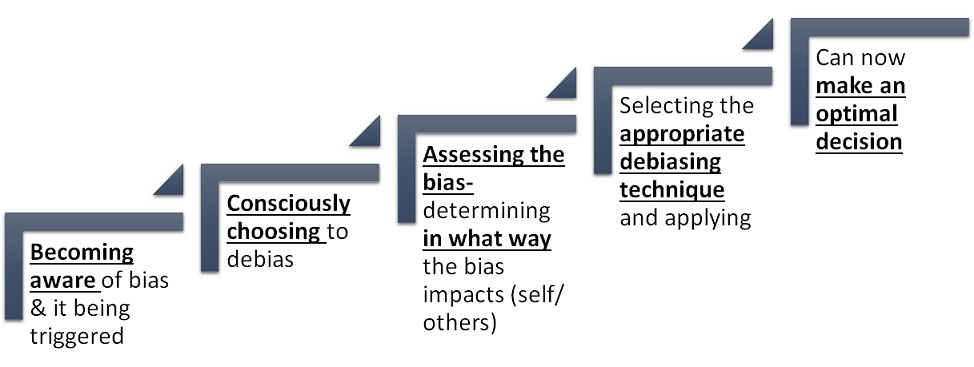

Having thoughts and feelings of scarcity automatically orient the mind towards unfulfilled wants and needs. Furthermore, scarcity often leads to lapses in self-control while draining the cognitive resources needed to maximize opportunity and display judgment. Willpower also is depleted, which makes one prone to feelings of giving up. People in this state attend to the urgent while neglecting important choices that will have a drastic effect on the future. A scarcity mindset is exactly that: a mindset.

Progressive Impact

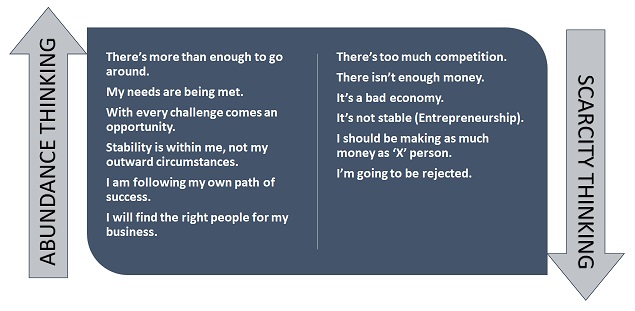

On the positive side, scarcity prioritizes our choices, and it can make us more effective. Scarcity creates a powerful goal dealing with pressing needs and ignoring other goals. For example, the time pressure of a deadline focuses our attention on using what we have most effectively. Distractions are less tempting. When we have little time left, we try to get more out of every moment.

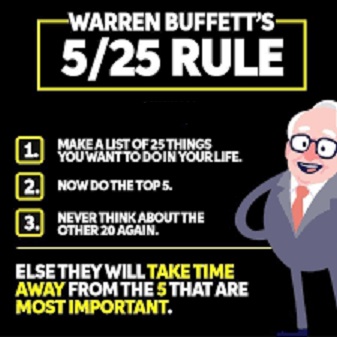

Scarcity contributes to an interesting and a meaningful life. When there is always time for everything, there is no urgency for anything. A life without limits would lose the beauty of its moments, and it would become boring. For example, resolution of midlife crises consists in accepting mortality. Midlife often heightens the feeling that there is not enough time left in life to waste. We overcome the illusion that we can be anything, do anything, and experience everything. We restructure our lives around the needs that are essential. This means that we accept that there will be many things we will not do in our lives.

Scarcity forces trade-off thinking. We recognize that having one thing means not having something else. Economists call this the opportunity cost—the alternative use of the money. Doing one thing means neglecting other things. However, slack frees us from making trade-offs. For example, as our budget grows, the purchase of the iPad takes up a smaller and smaller portion of our disposable income. Thus, a bigger budget makes decisions less consequential and lessens feelings of scarcity.

Degenerative Impact

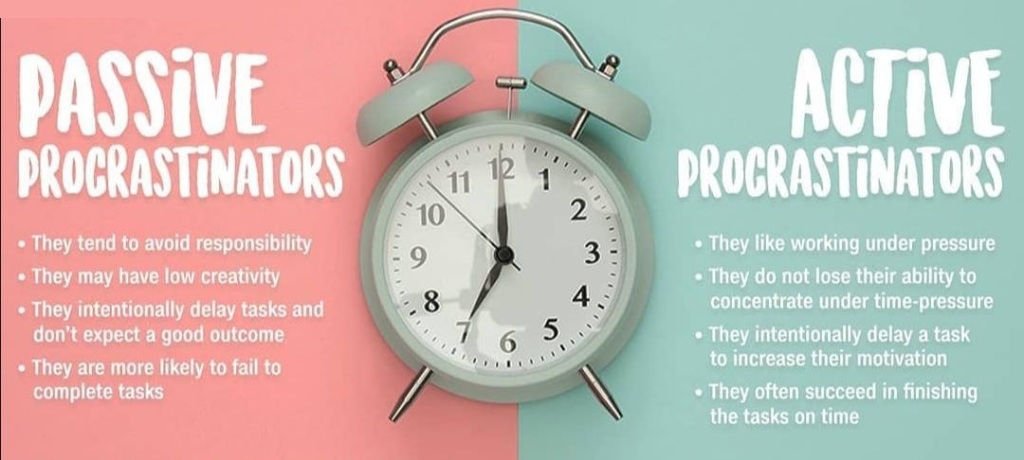

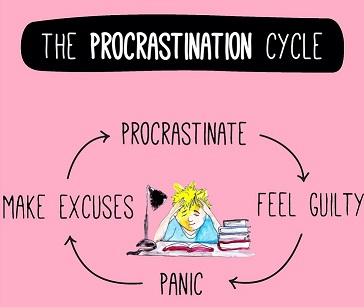

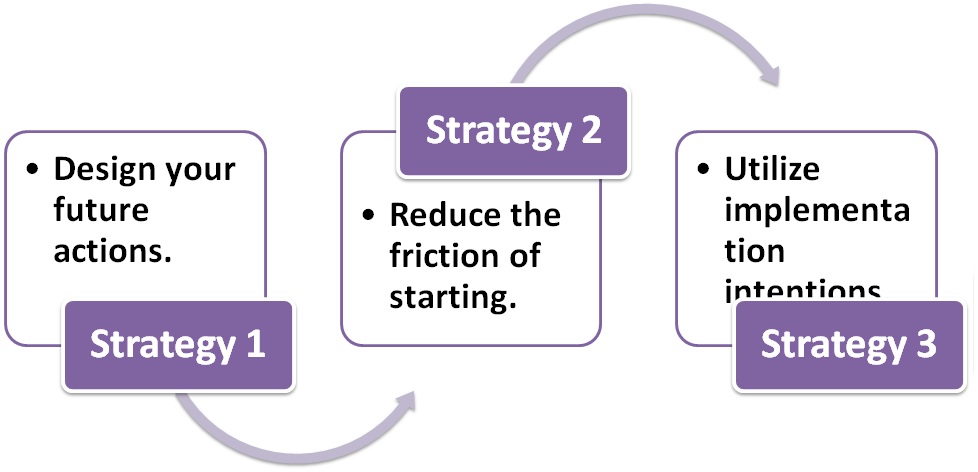

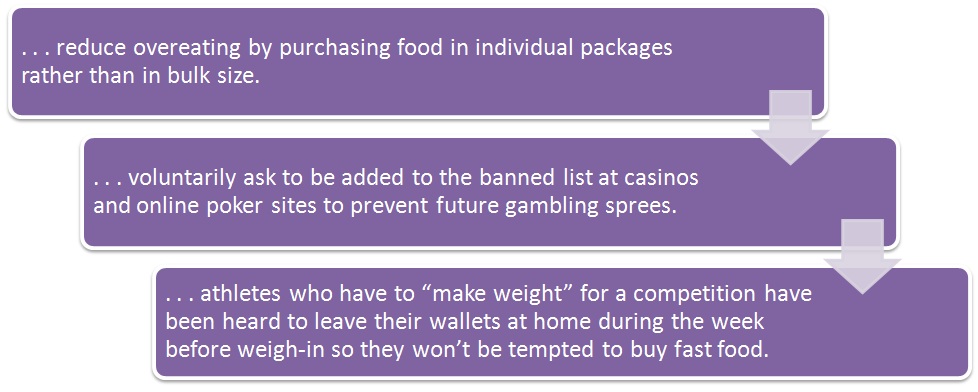

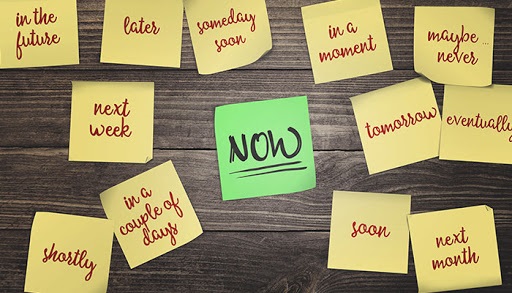

The context of scarcity makes us myopic (exhibiting bias toward here and now). The mind is focused on present scarcity. We overvalue immediate benefits at the expense of future ones (e.g., procrastinate important things, such as medical check-ups, or exercising). We only attend to urgent things and fail to make small investments even when future benefits can be substantial. To attend to the future requires cognitive resources, which scarcity depletes. We need cognitive resources to plan and to resist present temptations.

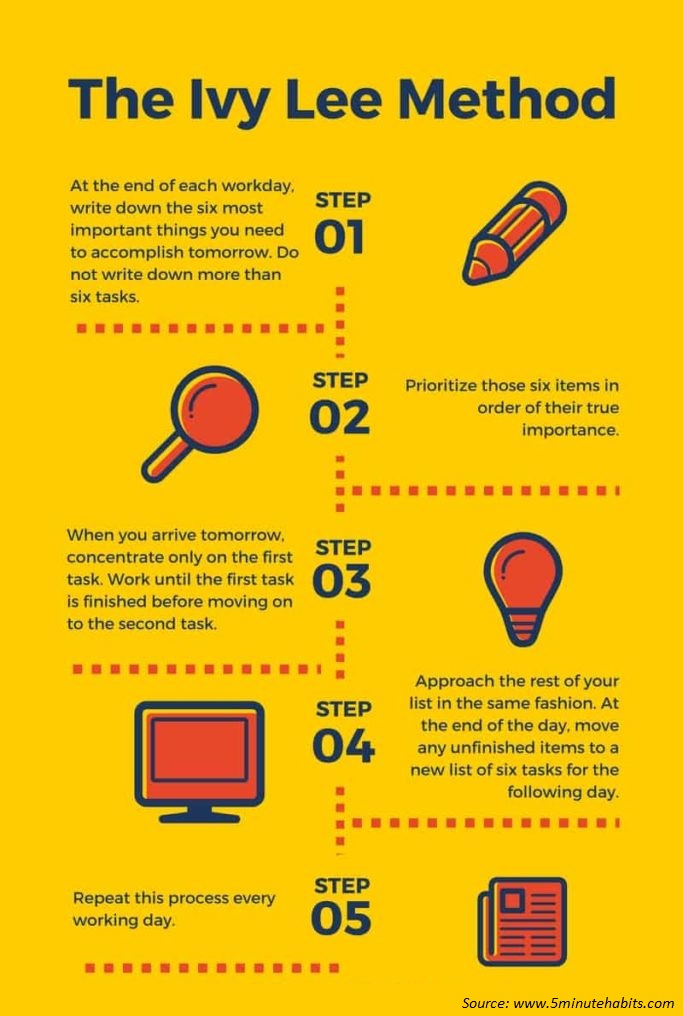

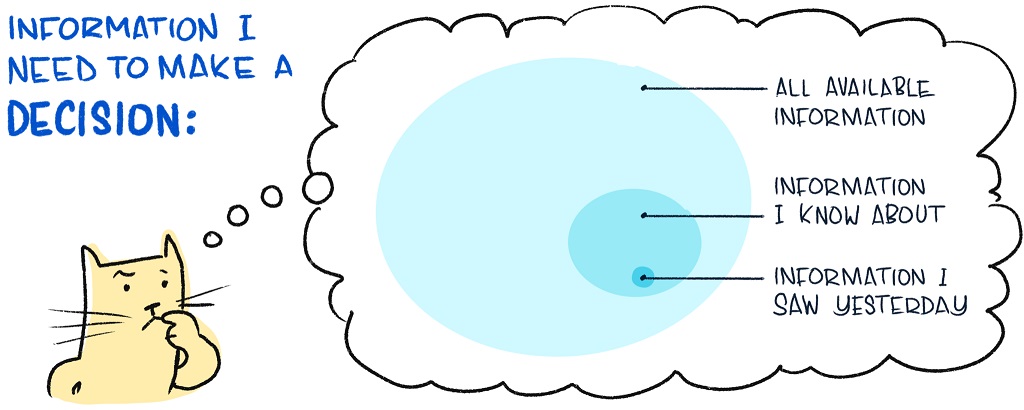

A key concern in the management of scarcity is to economize cognitive resources. Cognitive resource is about allocating our limited information-processing abilities. Concentrating our effort on one or—at most—a few goals at a time increases the odds of success. For example, research suggests that the best way to get more done in less time requires one to avoid exhaustion and skillfully manage energy by getting sufficient sleep (8 or more hours), more breaks, or daytime naps.

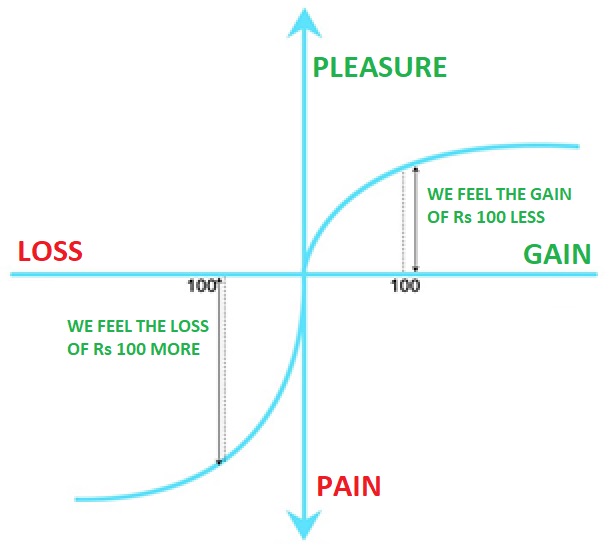

Loss Aversion:

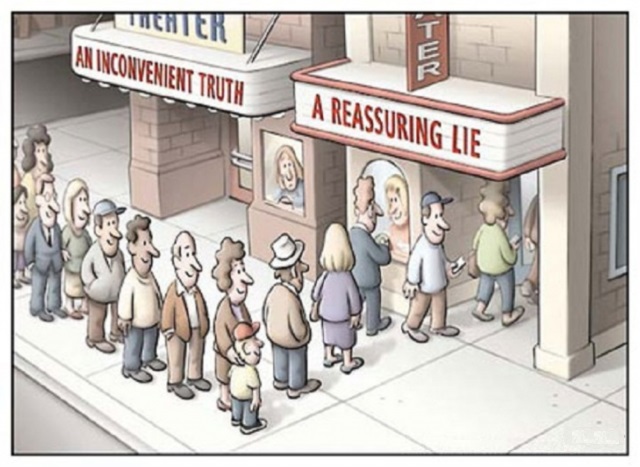

When we see something which we want becoming less available, we get physical anxiety. This is worse when there is direct competition. The focus narrows and emotions rise making it difficult to feel calm. Opportunities appear more valuable to us when availability is limited. The idea of potential loss plays a significant role in human decision making. People seem to be more motivated by the thought of losing something than by the thought of gaining something of equal value. We prefer avoiding a loss than pursuing gains. The FOMO(Fear of Missing Out) is directly associated with this.

Psychological Roots:

Psychological Reactance Theory:- ‘Reactance is unpleasant motivational arousal that emerges when people experience a threat to or loss of their free behaviors. So, when something (a product or service) which is generally easily available becomes scarce, this perceived ‘threat’ to our freedom to have it makes us crave it significantly more than before.

Anticipated Regret:– Another unpleasant emotional state that may influence our buying choices is anticipated regret. In other words, the feeling we experience when we imagine what it would be like if the decision we are currently making is the wrong one.

***To be continued in Chapter 02 (Forms of Scarcity Mindset, Instances around us, ways to identify and mitigate) Link to Chapter -02:

Content Curated By: Dr Shoury Kuttappa