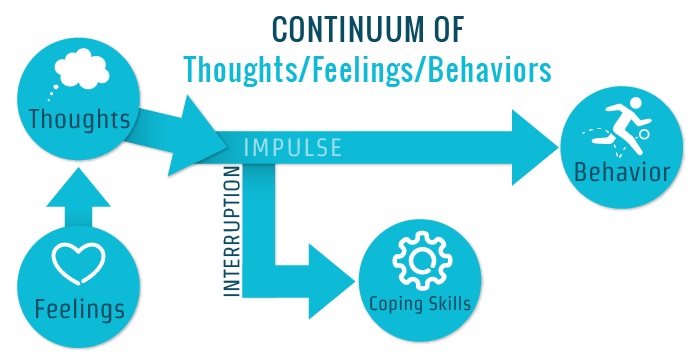

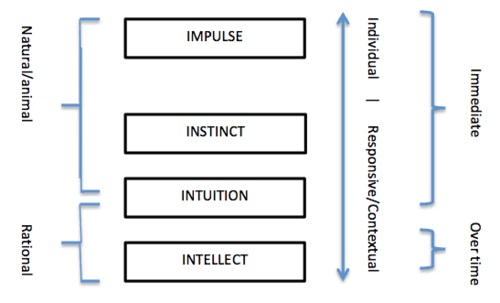

Negotiation is an inherent part of influencing someone. In a work environment, it can be external negotiations, with a supplier or a client; or internal, with a boss, colleague or subordinate. But we must also negotiate with ourselves, be aware of instinctive reactions (psychological and physical), in order to regulate them and respond consciously and appropriately to the circumstances so that we get the best result.

All negotiations comprise two dimensions: The “substance,” meaning the subject matter or objective of the negotiation, and the “relationship,” i.e., the interaction or connection with the other person. We negotiate because we are looking to gain something or because the relationship with the other party is important. These two dimensions are always in play and under tension because the things we do to improve the substance—such as not making concessions—damage the relationship to a certain degree. Conversely, when we try to grow the relationship, decisions like being flexible can lessen the substance, which in turn becomes a source of frustration.

Our Emotional Reactions

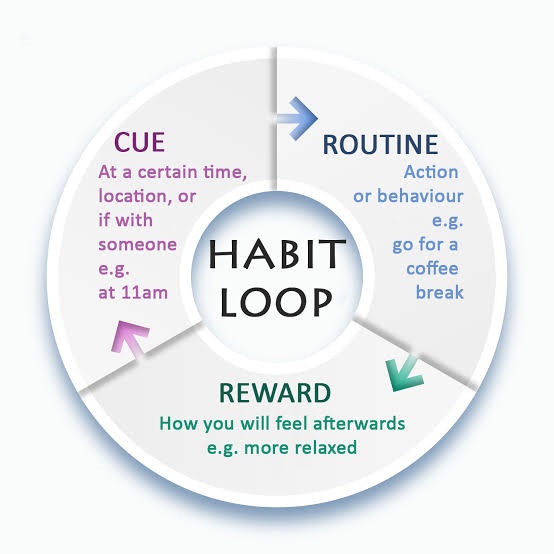

In order to change, we must be aware of the behaviour that needs changing. Most of us fall into assumptions or mindsets about negotiation, generally as a result of emotional reactions that trigger certain behaviours and can have an influence on either maximizing our benefit or achieving the exact opposite. Indeed, oftentimes the problem is not the behaviour itself, but rather the mindset that generates that behaviour. Changing mindsets will automatically bring about different results. Some of the most common assumptions regarding negotiation are:

Competing?: . . . Not always. It is incorrectly assumed that negotiating implies competing. It is necessary sometimes, but not always. The key is being capable of adapting our behavior to the circumstances.

“Wait and see” vs. “be proactive.” . . . . Perhaps, due to ignorance, most people go to negotiations hoping to see how the other party behaves and then react accordingly. We tend to be reactive, which is a mistake because we have a huge capacity to influence others if we are proactive, if we have a definite plan and a clear approach to negotiating. When it comes to reactivity, the advice is: “Do not react. Wait, buy time, then respond.”

The value available is definite: . . . . That’s why we compete: We think we must divide what’s there and take the biggest piece, when it’s easy to increase the value available in a negotiation.

Not identifying intention with impact: . . . . There is a clear lack of communication in negotiations. The counterpart’s intentions are always misinterpreted because that makes evolutionary sense. If an ambiguous signal is sent, the recipient will always interpret it in the worst possible way. In a negotiation, we need to send clear messages.

Short term versus long term: . . . . . We tend to think in the short term, however collaborative thinking in the long term is more beneficial.

As for this last assumption, it is also important to mention reputation, which is difficult to build but can be destroyed in a heartbeat. Having a short-term mentality keeps us from thinking about the implications of our actions in the long run. Nevertheless, we should not simply place our trust if we do not have a basis for doing so. The key is to be trustworthy, but not overly trusting.

The first key to negotiation, thus, is the mindset, being aware that we carry baggage that makes us react in a certain way that is not always the most appropriate. If we change our mindset, we change the behaviour and can get different results. Most of us fall into assumptions or mindsets about negotiation, generally as a result of emotional reactions that trigger certain behaviours and can have an influence on either maximizing our benefit or achieving the exact opposite.

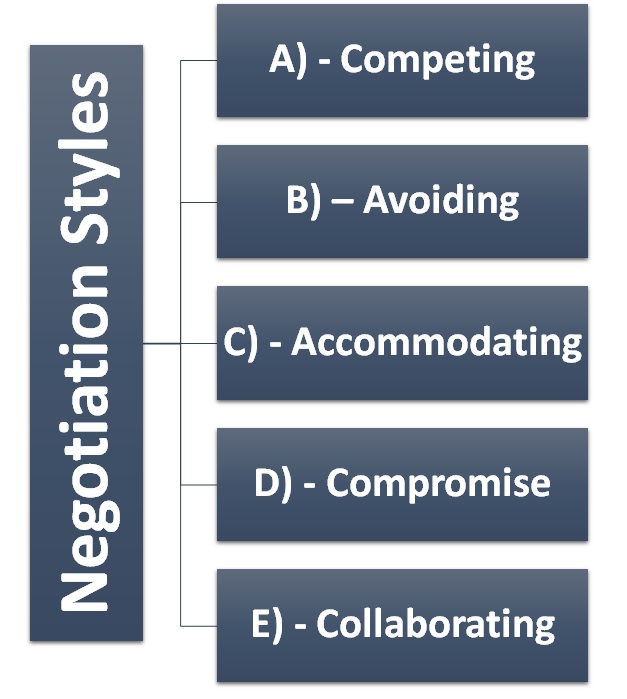

Negotiation Styles

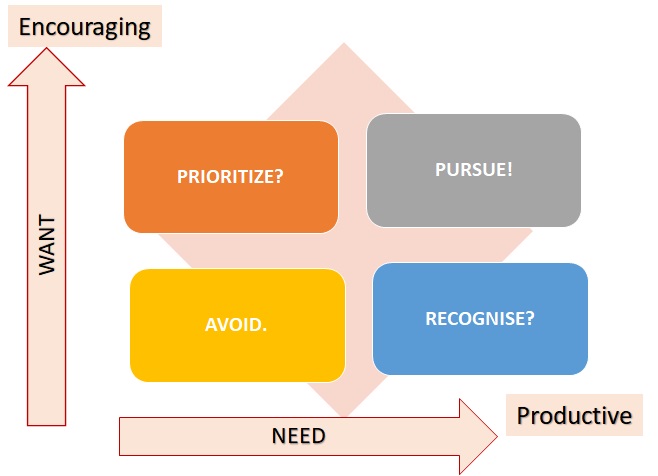

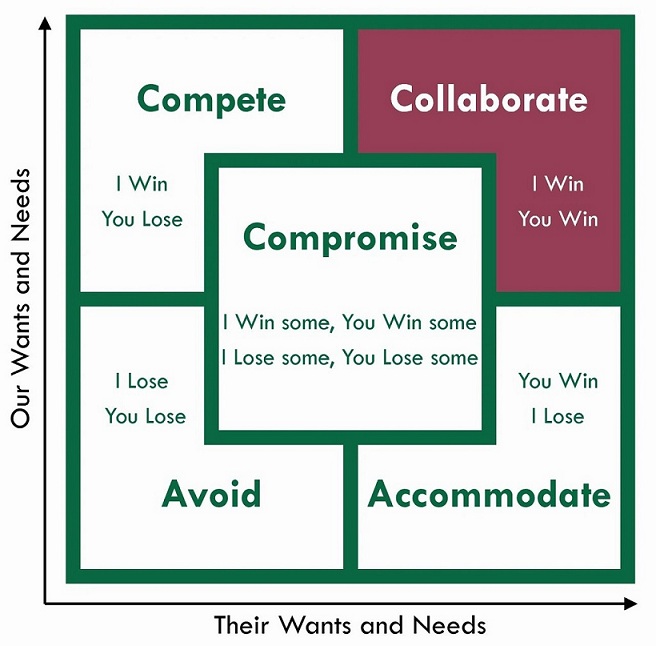

There are five styles of negotiation, depending on how much the substance and relationship matter:

A) – Competing: . . . . There are people for whom substance is everything and the relationship doesn’t matter. Their style of negotiation tends to be aggressive: they compete. The benefit is that it always gets great results; the downside is that in the long run nobody wants to play with them.

B) – Avoiding: . . . . . When neither substance nor relationship matters, we tend to avoid it.

C) – Accommodating: . . . . .. When the substance is minor and inconsequential, and the relationship is very important, we tend to adapt to their requests. The long-term problem is that the substance will be insignificant.

D) – Compromise: . . . . .. When both dimensions matter (neither for you nor for me), the decision is to compromise (50-50%) because it is quick and seems equitable.

E) – Collaborating: . . . . .. This style maximizes both the relationship and the substance. It is quite complex and definitely not innate. It requires training and counteracting our impulses. We can only collaborate when we have enough time and knowledge and we care about both dimensions.

Which style is best? That depends on the circumstances. We all have a predetermined style that we feel most comfortable with and we unconsciously revert to that in stressful situations, such as negotiations. We must be clear on two objectives: first, being aware of our own automatic reaction; second, using a style that fits the circumstances. From the outset, we must take into account that the collaborating style is not innate, since our instinctive reactions often lead us to compete, avoid, accommodate or compromise.

To be able to move from positions to interests we must ask open questions, showing curiosity, without prejudice.

Elements for a Collaborative Negotiation Framework

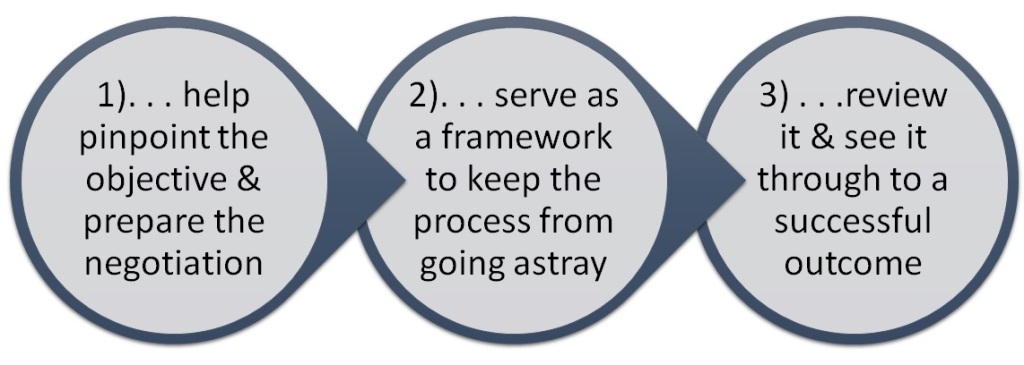

Generally, simple criteria are used to define what a successful negotiation looks like. However, the criteria are lacking and leave us exposed to manipulation. Thus, it requires a more complex model that can:

Some key elements that are key in a negotiation process are:

A) – Interests: . . . . . The needs and motivations that lead to negotiation. It is important to differentiate negotiations from positions, which are a unique way of satisfying an interest or a specific demand. We should ask about the interests of each party because the objective of a negotiation is to reach the point where both our interests and those of the other party are satisfied, so that the agreement is fulfilled. We need to make our own interests known in order for them to be met, but we should never reveal how important our top priorities really are. It is also vital to know what others want, so that we don’t offer them too much.

B) – Options: . . . . . Once both parties’ interests have been identified, that is when solutions are proposed. The key is to come up with as many options as possible and settle on the one with the most value. It is important to create a space that allows for brainstorming, and to separate the output of options from the selection process. This allows us to maximize the chances of creating an option that achieves the highest possible satisfaction of the interests at stake.

C) – Criteria for legitimacy: . . . . . When options abound, some will benefit one party, and some will benefit the other. The goal is to reach equitable agreements by means of shared criteria for legitimacy.

D) – Alternatives: . . . . . This implies everything that can be done to satisfy our interests without needing the other party, away from the negotiating table. If there are alternatives, they will always have to offer us something better.

E) – Relationship and communication: . . . . . In a negotiation, the goal is to spend as much time as possible talking about interests, options and criteria for legitimacy. This requires fluid communication and a fluid relationship. A variety of tools can be used to move from positions (demands of the negotiating parties) to interests (underlying needs that are not obvious). Foremost of these is the asking of open questions, showing genuine curiosity, without prejudice. We cannot have mindset of certainty; instead, we need to turn the negotiation into a learning-oriented conversation.

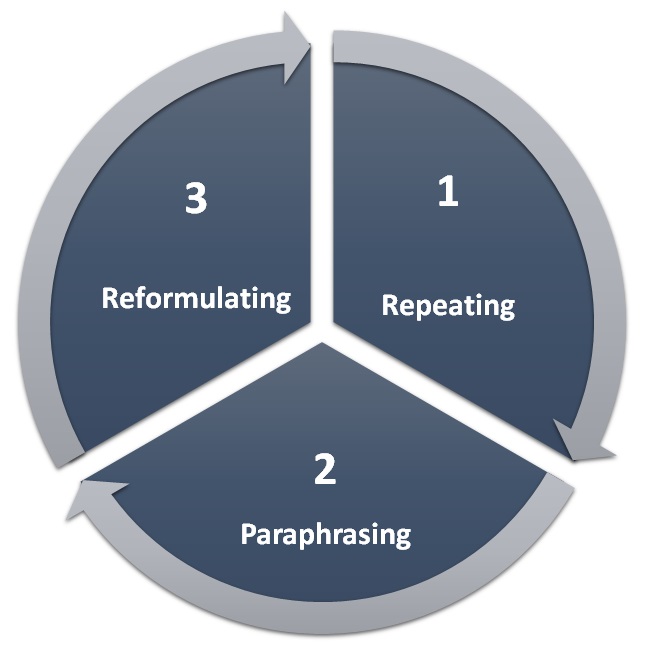

After asking a question, silence comes into play. When used properly, given the discomfort it generates, it can help us get answers. We must also be aware of the emotional reactions it triggers in us and not react to it if we do not wish to. Next, we have listening, which should be approached as a two-way tool: We must listen not only to understand, but also to make the other person feel heard. And to achieve this second aim, we must demonstrate our understanding. Here are three methods for doing so:

- Repeating: . . . . .. The advantage is that it is very easy, but it does not really convey true understanding. There is no risk of mistakes; it allows us to continue the conversation.

- Paraphrasing: . . . . .. To say the same thing in our own words conveys a greater degree of understanding, but does not allow the conversation to move forward; it is like an insurance policy for having a smooth communication.

- Reformulating: . . . . .. This is a negotiator’s secret weapon, which opens any and all doors. It consists of constantly reflecting interests, making the person feel heard and understood. But, instead of echoing what they express, which is usually positions, it is about conveying the interests in a positive light while looking toward the future.

Again, the key to negotiation is changing mindsets. Simply by changing the purpose of the conversation, we will get better results. The very process of listening with genuine curiosity and showing understanding, not conformity, makes the relationship and communication flow, enabling negotiation to become an activity that strengthens relationships and maximizes value.

Content Curated By: Dr Shoury Kuttappa