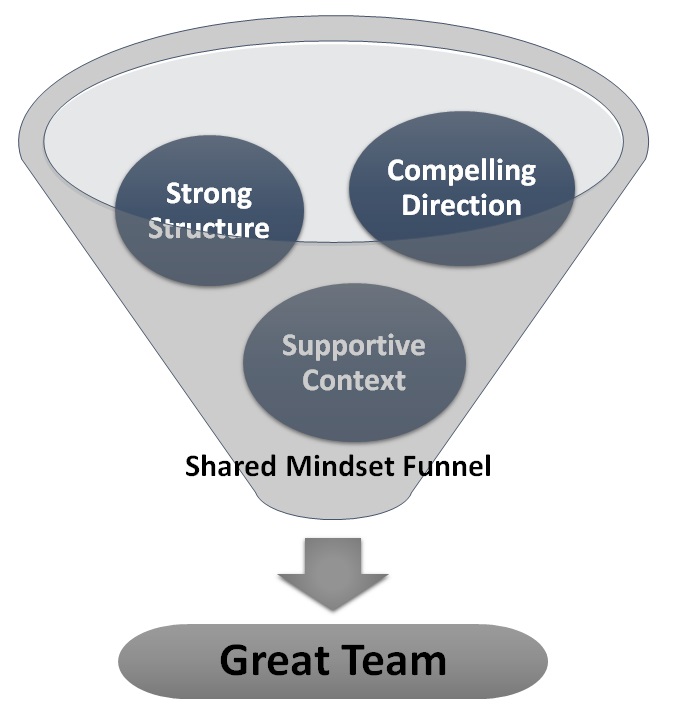

The pandemic has had a huge impact on individual and collective health and prosperity, and no one knows when our economy and our society will be healthy again. Yet opportunities exist. If companies and leaders can inspire team members to proactively solve problems, set aside old practices, test and prove innovative ways to work, and pilot new systems, the likelihood of organizations surviving — and, indeed, thriving — is much greater.

The single most important component are caring leaders: leaders who adapt to serve their employees and their companies and create positive traction. It is important for leaders to take steps to build trust and cooperation among their employees to maximize productivity and team satisfaction. Modelling best behaviours and creating shared experiences, they must evolve and adapt, and some behaviours that can help them are:

1. Develop Rules Of Engagement

Ask people what it takes to have a great team, what the definition of a great teammate is, and what actions each needs to participate in to support those definitions. Once done, ask what phrase could be used, without people being defensive, to create accountability. What it does is it levels the playing field and re-establishes trust.

2. Define Clear Commitments

We lose trust when we perceive others have not followed through on what we expect; yet these commitments are often not clearly articulated, mutual and measurable. In new teams or in teams trying to recover trust, it is important to have clearly articulated agreements and accountability measures to ensure everyone involved has aligned expectations.

3. Show Trust First

As the leader, are you trusting them? Where are you holding the reins too tightly, thinking you are best to handle a particular client or project? What information are you holding back, assuming others cannot handle it? Trust them more, and they will begin to learn they can trust, too.

4. Share and Be Receptive

Trust is determined by openness, credibility, and respect, practiced consistently. Leaders must foster an environment where others’ differences are accepted and look out for others’ welfare. Leaders who share thoughts and feelings and who are receptive to the thoughts and feelings of others build trust.

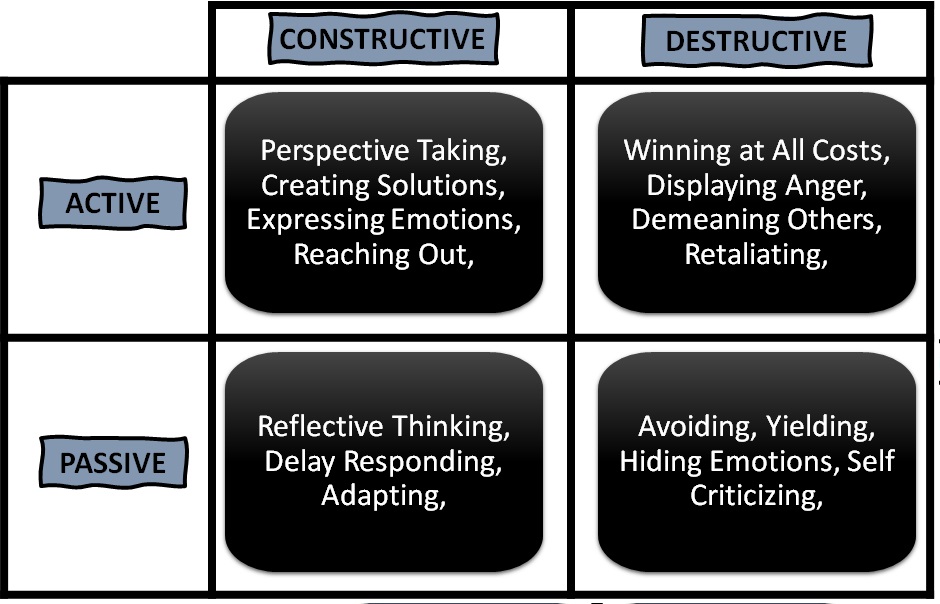

5. Model Respectful Argumentation

Establish a regular routine that supports the process of argumentation during all team meetings. Argumentation among team members instigates positive tension that leads to mutual respect, trust, and innovation. By learning how to respectfully disagree, people learn that there is no need to mistrust someone with a different perspective, because argumentation feels a lot different than mere arguing.

6. Identify Why Trust Is Low

Think of trust as deposits or withdrawals from an account. Low trust is a result of too many withdrawals. There are several areas that can build or break trust with teams. One thing leaders can do is to identify the reasons for low trust. By getting down to the root issues you can start to rebuild trust.

7. Have Team Members Interact on A Personal Level

Create an opportunity for the team to interact on a personal level at a retreat, challenge, or event. Make it easy for people to be authentic, tell stories and reveal their character. It is with this shared experience that a structured dialogue about earning each other’s trust and respect can evolve into the best way to work together as team. A didactic exercise alone cannot produce trust.

8. Share A Regular Meal

People are hard to hate up close, and nothing brings togetherness like sharing a meal. Engage in activities (a monthly team lunch or coffee) focused on nonwork discussion. Engage in personal sharing exercises, discuss vacations and personal and professional goals, or have a self-awareness workshop, such as a personal assessment tool, to create mutual understanding. Teams that eat together build stronger bonds.

9. Understand Communication Styles

We all have different behavioural styles, and when we encounter someone who approaches tasks or communicates differently than we do, it can lead to mistrust. By discussing motivators, work styles and how each style prefers to communicate, you will bridge misunderstandings and begin to build trust.

10. Create A Necessity

From a practical standpoint, it is all about creating a “necessity.” Human behaviour is most likely to adapt when changes are a matter of survival. The most effective method I have seen work is to create that necessity. Put those that you perceive as not trusting each other into a team and define the project success in a way that forces trust building.

11. Don’t Be Afraid to Be Vulnerable

It is so powerful when a leader shows vulnerability to their team. When anyone is vulnerable their team often responds with empathy, which starts a cycle of trust. If you need to build trust more quickly, hold an offsite and ask everyone on the team to develop and share two growth goals with the entire team. This provides everyone with an equal opportunity to be vulnerable and to support each other.

12. Teach Safety Instead

We cannot teach trust any better than we can teach a fool proof method of falling in love. Trust equals an outcome, rather than a catalyst. Instead, teach safety and trust will grow. When we feel safe, we trust. Try criticizing in private, praising in public or other safe practices, and watch the trust build on your team.

13. Learn Each Other’s Stories

Everyone has a personal history that impacts how they show up in their professional setting and the lens by which they view the world. Establishing trust requires team members be given the opportunity to share the stories that have shaped them. This allows the armour to come down so they can see each other authentically and develop the compassion that will guide them through the challenging times.

14. Do Charitable Work Together

Sometimes the best building of bonds and trust is outside the walls of the organization. Those who serve others by building a Habitat house, meeting kids and families under cancer care, or serving meals and educating the homeless often get something far greater than getting along better at work. Volunteer experiences where trust can be built often directly translate positively and immediately.

Content Curated By: Dr Shoury Kuttappa.