We are hard-wired to fight or flee under threat, so it is normal to want to act out in defence when we experience or observe the injustices in today’s world. But when we respond with our primitive, survive mind, it raises the stakes for impulsive and unreasonable reactions and in some cases violence, even death. Our survive brain can colonize our hearts and dwarf our humanity if we continue to allow it—as evidenced by large-scale injustices such as racially motivated murders, hate crimes, violent protests, police brutality, deadly reactions to the COVID-19 lock-down and global terrorism.

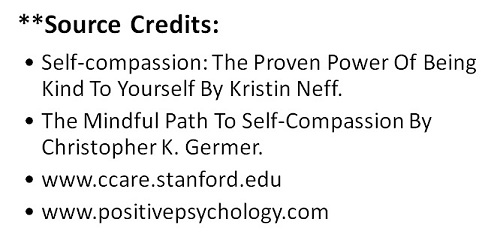

Survive Mind Versus Thrive Mind

We have a choice to permit our lives to be driven by our survive mind’s violent reactions or drawn from our thrive mind’s calm, compassionate, and clear-minded actions. Our lives are shaped from the inside out. If we lose our inner connection, in small ways and big, our personal lives and the world unravel. It starts with each of us exercising our own levelheadedness, self-control, and inner calm at an individual level.

All of us have a running monologue in our heads with the intention to control ourselves whether it is to stop from blowing up at the injustice we see in news feeds, eating another slice of pizza, or blurting out at a colleague who talks over us in a virtual meeting. But how many times have we said or done something we wish we could take back? We can blame our impulsive, self-immersed, non-thinking survive brain. Once we become clearheaded and regret what we said or did, we have shifted into our reflective, self-distanced, thinking thrive brain. But what if we could act more from our thrive brain (and react less from your survive brain) in the first place?

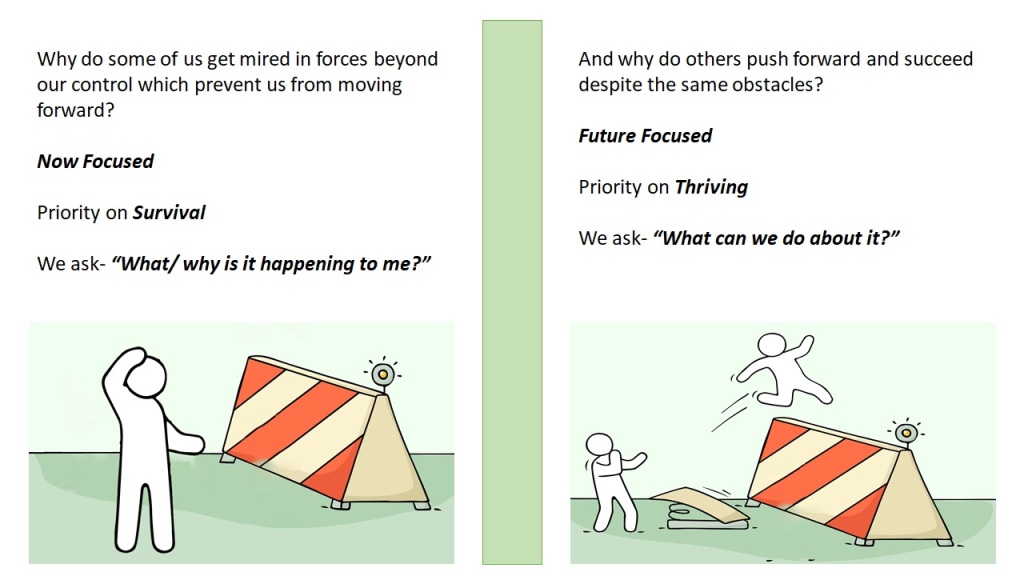

Self-Talk: Thrive talk instead of survive talk creates greater resilience.

Self-talk and how we consciously use it is a relatively effortless form of self-control in many different areas of our lives: diet, athletic performance, scholastic achievement, emotion regulation and impulsive behaviors. The way we talk to ourselves can help us survive or thrive.There was a time when people who talked to themselves were considered “crazy.” Now, experts consider self-talk to be one of the most effective therapeutic tools available. The science of self-talk has shown time and again that how we use self-talk makes a big difference.

We have an inner voice that provides a running monologue on our lives throughout the day and into the night. This inner voice, combining conscious thoughts with unconscious beliefs and biases, is an effective way for the brain to interpret and process daily experiences.

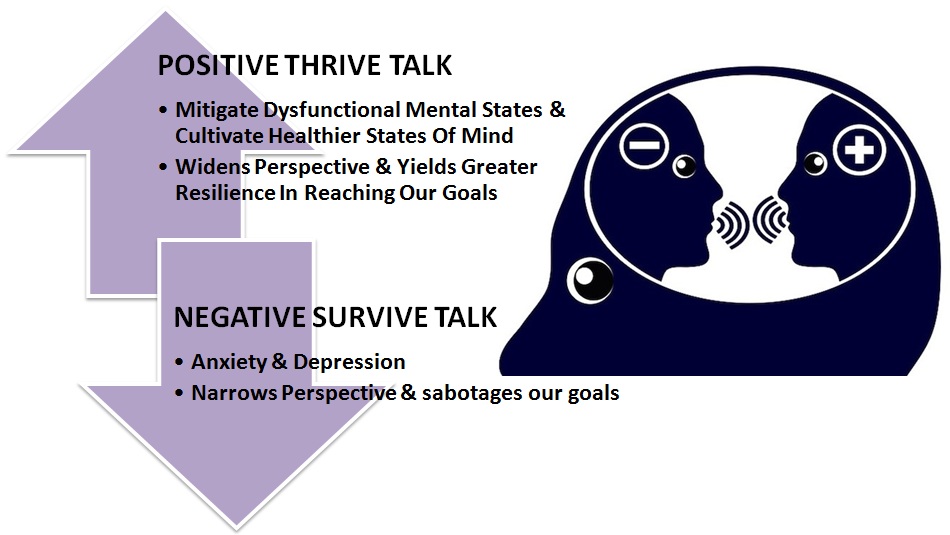

According to research, we have greater self-control when we use self-distanced self-talk from our thrive brain that entails using our name and non-first-person pronouns (instead of self-immersed first-person pronouns of “I” from our survive brain). Self-distancing gives us psychological distance from the survive brain’s egocentric bias which in turn enhances self-control, lowers anxiety, bolsters confidence, reduces impulsivity, improves emotion regulation, and cultivates wisdom over time. The reason for this difference is that third person self-talk leads us to think about ourselves similar to how we think about others and gives us agency to regulate our frustration, anger, or fear simply by the way we use internal dialogue.

Our “inner voice” can give us the self-control to stop us from making impulsive decisions. Research has confirmed that we act more impulsively when we cannot use our inner voice or talk to ourselves as we are performing tasks. Self-talk incorporating non-first-person pronouns (like the collective “we”) can enhance athletic performance and the ability to regulate thoughts, feelings and behaviours and help us to avoid rumination and improve performance with greater perspective, calm and confidence.

Self-Distancing

As human beings, our sense of self, or ‘ego’ governs a large part of our behavior, like our interactions with other people, our sense of self-worth and the image we have of ourselves in our minds. And often this image is very fragile, susceptible to all kinds of doubt and insecurity. Recent studies show that creating an alter ego or thinking of one’s self in the third person can go a long way in boosting morale and instilling confidence.

Research shows silently referring to ourselves by name instead as “I,” gives us psychological distance from the primitive parts of our brain. It allows us to talk to ourselves the way we might speak to someone else. The survive mind’s story is not the only story. And the thrive mind has a chance to shed a different light on the scenario. The language of separation allows us to process an internal event as if it happened to someone else. First-name self-talk or referring to ourselves as “you,” shifts focus away from our primitive brain’s inherent egocentricism. Studies show this practice lowers anxiety, gives us self-control, cultivates wisdom over time and puts the brakes on the negative voices that restrict possibilities.

First-name self-talk is more likely to empower us and increase the likelihood that, compared to someone using first-person pronoun self-talk, we see a challenge (thrive mind) instead of a threat (survive mind).

The Language of Separation

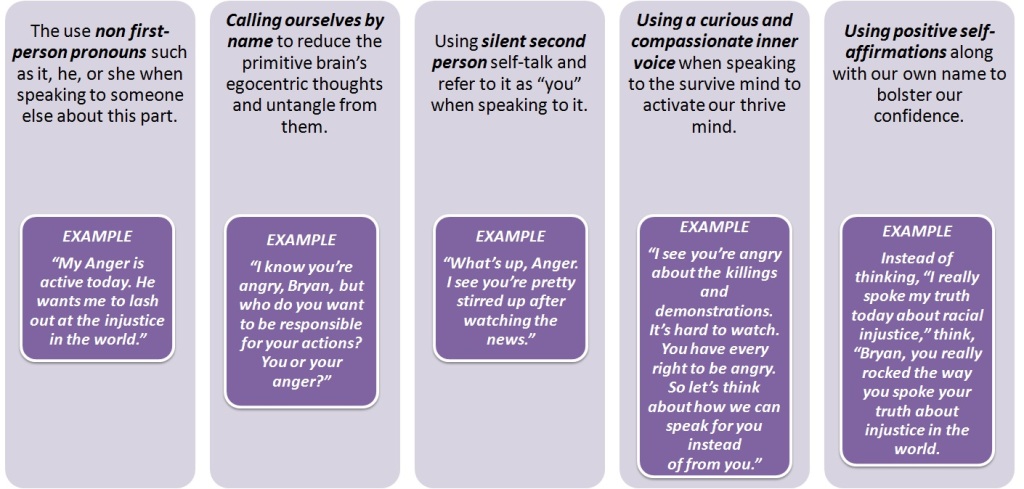

The language of separation allows us to process an internal event as if it happened to someone else. Thus, our survive mind’s story is not the only story and the thrive mind has a chance to shed a different light on the scenario. Experts have found that the best approach to deal with the survive mind is to respond as if it is another person. We must remember that the voice is not us. Some Examples of the language of separation and practicing self-distancing are:

Broaden-and-Build: The Big Picture

It sometimes helps to think of ourselves as the narrator, instead of the actor, of our thoughts and feelings when we are in a disturbing scene. Scientists report that narrative expressive writing creates a self-distanced versus self-immersed perspective and helps us overcome egocentric impulses, reduce stressful cardiovascular effects, and apply wise reasoning. With this form of self-distancing, we can process and make meaning from a bird’s-eye view instead of a personal perspective, fostering forward movement as opposed to rumination and re-experiencing the same negative emotions over and over again.

Like the zoom lens of a camera, Mother Nature has hardwired our survival brain for tunnel vision to target a threat. Our heart races, eyes dilate, and breathing escalates to enable us to fight or flee. As our brain zeroes in, our self-talk makes life-or-death judgments that constrict our ability to see possibilities. Our focus is narrow like the zoom lens of a camera, clouding out the big picture. And over time we build blind spots of negativity without realizing it. Self-talk through our wide-angle lens allows us to step back from a challenge, look at the big picture, and brainstorm on a wider range of possibilities, solutions, opportunities and choices.

Self-Affirmations

In 2014, Clayton Critcher and David Dunning at the University of California at Berkeley, conducted a series of studies showing that positive affirmations function as “cognitive expanders,” bringing a wider perspective to diffuse the brain’s tunnel vision of self-threats. Affirmations help us transcend the zoom-lens mode by engaging the wide-angle lens of the mind. Self-affirmations help cultivate a long-distance relationship with their judgment voice and see ourselves more fully in a broader self-view, bolstering our self-worth.

Relationships with Our ‘Parts’

When we notice that we are in an unpleasant emotional state—such as worry, anger, or frustration—holding these parts of us at arm’s length and observing them impartially as a separate aspect of us, activates our thrive talk (clarity, compassion, calm). Thinking of them much as we might observe a blemish on our hand allows us to be curious about where they came from. Instead of pushing away, ignoring, or steamrolling over the unpleasant parts, the key is to acknowledge them with something like, “Hello frustration, I see you are active today.”

This simple acknowledgment relaxes the parts so we can face the real hardship—whatever triggered them in the first place. This psychological distance flips the switches in our survive brain and thrive brain at which point we are calm, clear-minded, compassionate, perform competently, and have more confidence and courage.

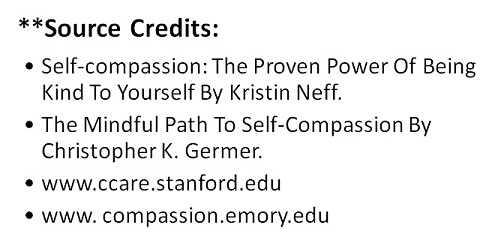

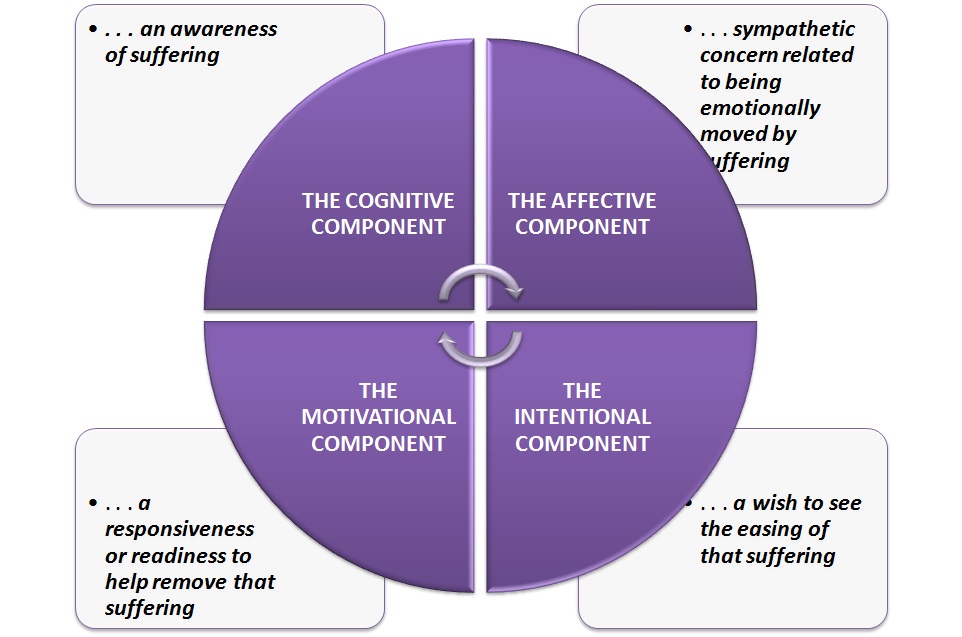

Self-Compassion

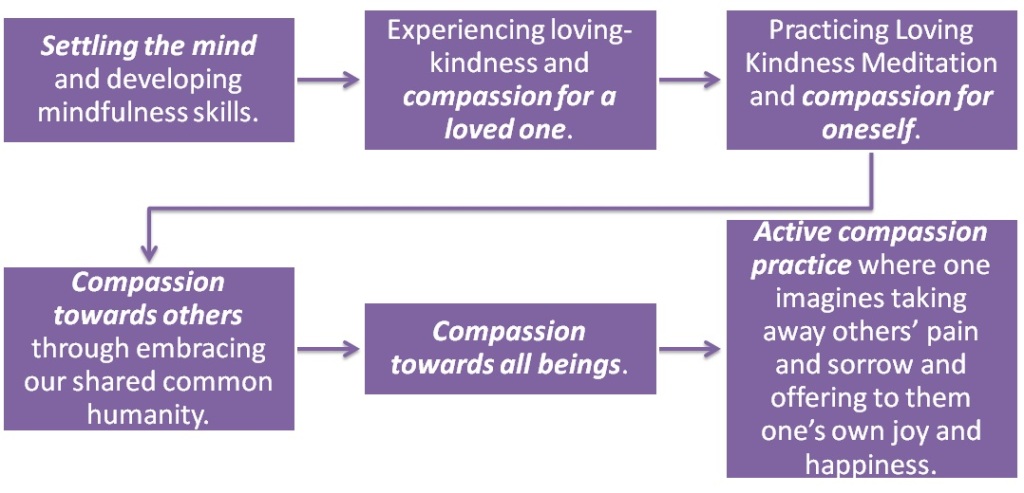

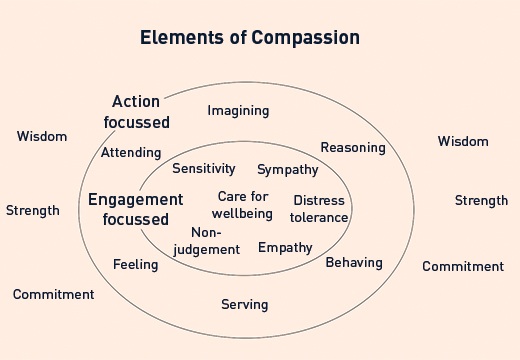

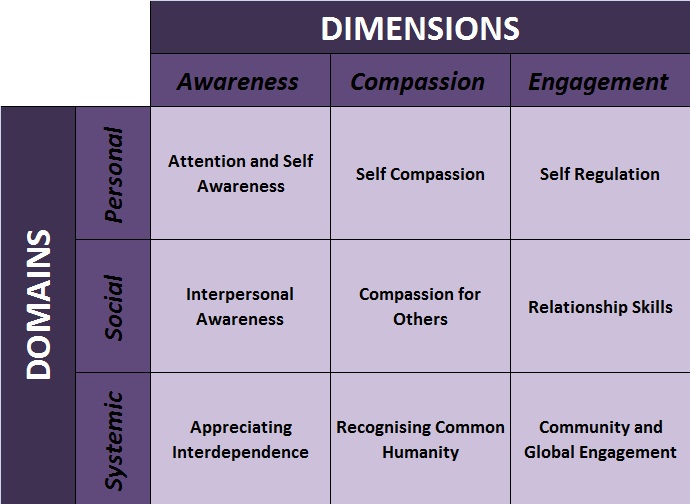

There is a direct link between self-compassion and happiness, well-being, and success. The more self-compassion we have, the greater our emotional arsenal. Studies show that meditation cultivates compassion and kindness, affecting brain regions that make us more empathetic to other people. Using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), the researchers discovered that positive emotions such as loving-kindness and compassion can be developed in the same way as playing a musical instrument or being proficient in a sport.

The expression of empathy has far-reaching effects in our personal and professional lives. Employers who express empathy are more likely to retain employees, amp up productivity, reduce turnover, and create a sense of belonging in the company. If we cultivate the habit of speaking with loving-kindness, we change the way our brain fires in the moment.

Research shows that when abrasive, survive self-talk attacks us, it reduces our chances of rebounding and ultimately success. Instead of coming down hard on ourselves, loving-kindness helps us bounce back quicker. Forgiving ourselves for previous slip-ups such as procrastination, for example, offsets further procrastination. When we talk ourselves off the ledge using self-distancing, compassion, and positive self-talk, we perform better at tasks and recover more quickly from defeat or setbacks—regardless of how dire the circumstances.

Content Curated By: Dr Shoury Kuttappa