Not doing something will always be faster than doing it. The same philosophy applies in other areas of life. For example, there is no meeting that goes faster than not having a meeting at all.This is not to say we should never attend another meeting, but the truth is that we say yes to many things we do not actually want to do. There are many meetings held that do not need to be held.

How often do people ask you to do something and you just reply, “Yes, OK.” Three days later, you are overwhelmed by how much is on your to-do list. We become frustrated by our obligations even though we were the ones who said yes to them in the first place. It is worth asking if things are necessary. Many of them are not, and a simple “no” will be more productive than whatever work the most efficient person can muster. But if the benefits of saying no are so obvious, then why do we say yes so often?

Why We Say Yes

We agree to many requests not because we want to do them, but because we do not want to be seen as rude, arrogant, or unhelpful. Often, we have to consider saying no to someone we will interact with again in the future—our co-worker/ spouse/ family/ friends. Saying no to these people can be particularly difficult because we like them and want to support them. (Not to mention, we often need their help too.) Collaborating with others is an important element of life. The thought of straining the relationship outweighs the commitment of our time and energy.

For this reason, it can be helpful to be gracious in our response. Do whatever favours we can, and be warm-hearted and direct when we have to say no. But even after we have accounted for these social considerations, many of us still seem to do a poor job of managing the trade-off between yes and no. We find ourselves over-committed to things that do not meaningfully improve or support those around us, and certainly don’t improve our own lives. Perhaps one issue is how we think about the meaning of yes and no.

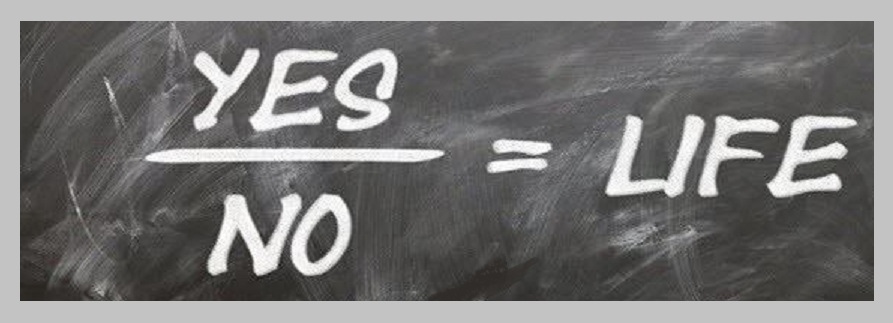

The Difference Between Yes and No: A Perspective

The words “yes” and “no” get used in comparison to each other so often that it feels like they carry equal weight in conversation. In reality, they are not just opposite in meaning, but of entirely different magnitudes in commitment. When we say no, we are only saying no to one option. When we say yes, we are saying no to every other option. Every time we say yes to a request, we are also saying no to anything else we might accomplish with the time.

Once we have committed to something, we have already decided how that future block of time will be spent.

The Role of No

Saying no is sometimes seen as a luxury that only those in power can afford. And it is true: turning down opportunities is easier when we can fall back on the safety net provided by power, money, and authority. But it is also true that saying no is not merely a privilege reserved for the successful among us. It is also a strategy that can help us become successful. Saying no is an important skill to develop at any stage of our career because it retains the most important asset in life: our time. If we do not protect our time, people will steal it from us.

We need to say no to whatever is not leading us toward our goals. We need to say no to distractions. If we broaden the definition as to how we apply no, it actually is the only productivity hack (as we ultimately say no to any distraction in order to be productive).

There is an important balance to strike here. Saying no does not mean we will never do anything interesting or innovative or spontaneous. It just means that we say yes in a focused way. Once we have knocked out the distractions, it can make sense to say yes to any opportunity that could potentially move us in the right direction. We may have to try many things to discover what works and what we enjoy.

Upgrading The No

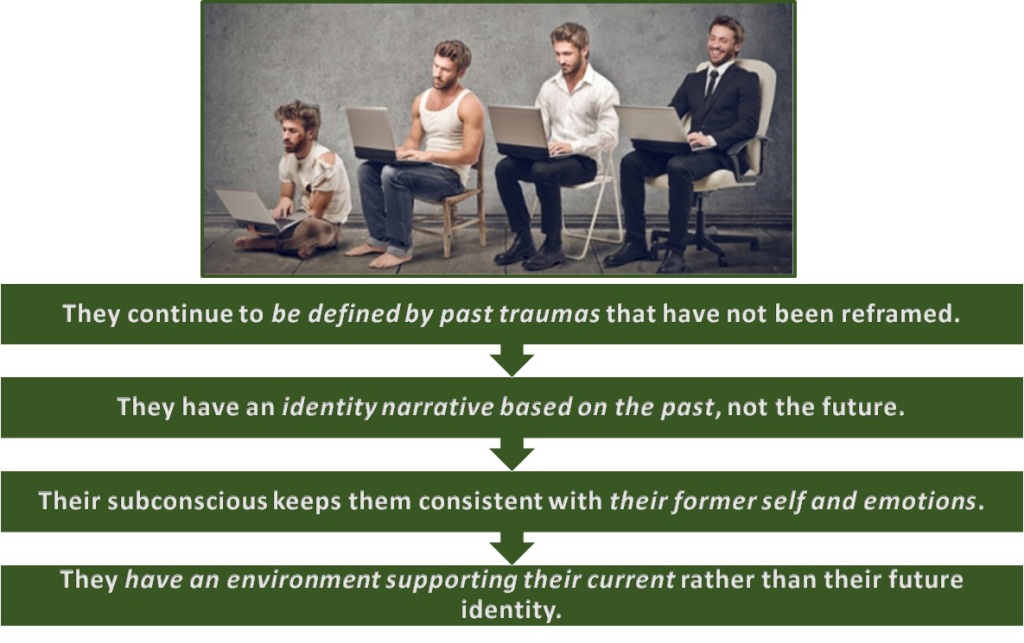

Over time, as we continue to improve and succeed, our strategy needs to change.The opportunity cost of our time increases as we become more successful. At first, we just eliminate the obvious distractions and explore the rest. As our skills improve and we learn to separate what works from what does not, we have to continually increase our threshold for saying yes.

We still need to say no to distractions, but we also need to learn to say no to opportunities that were previously good uses of time, so we can make space for great uses of time. It is a good problem to have, but it can be a tough skill to master. In other words, we have to upgrade our “no’s” over time. Upgrading our no does not mean we will never say yes. It just means we default to saying no and only say yes when it really makes sense. The general trend seems to be something like this: If we can learn to say no to bad distractions, then eventually we will earn the right to say no to good opportunities.

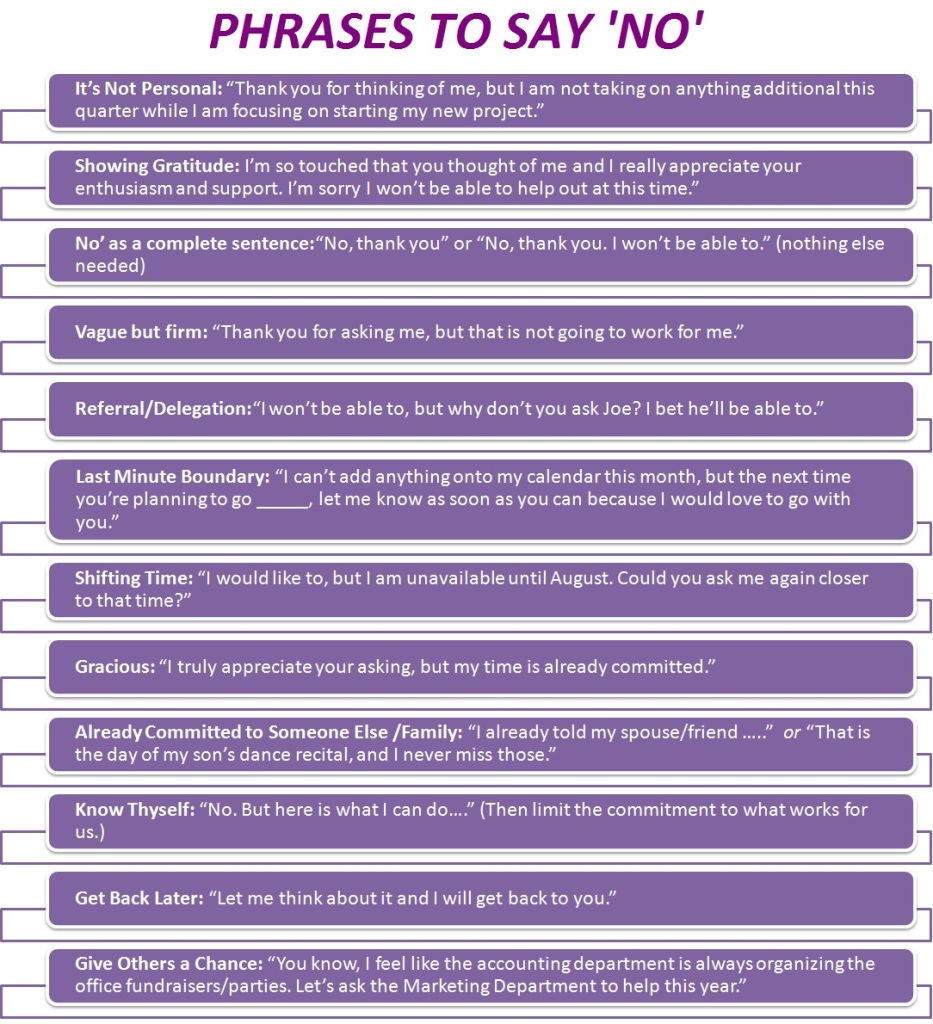

How to Say No

Most of us are probably too quick to say yes and too slow to say no. It is worth asking ourselves where we fall on that spectrum. One trick is to ask, “If I had to do this today, would I agree to it?” It is not a bad rule of thumb, since any future commitment, no matter how far away it might be, will eventually become an imminent problem. If an opportunity is exciting enough to drop whatever we are doing right now, then it is a yes. If it is not, then perhaps we should think twice.

It is impossible to remember to ask ourselves these questions each time we face a decision, but it’s still a useful exercise to revisit from time to time. Saying no can be difficult, but it is often easier than the alternative. It is easier to avoid commitments than get out of them. Saying no keeps us toward the easier end of this spectrum. What is true about health is also true about productivity: an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.

The Power of No

More effort is wasted doing things that don’t matter than is wasted doing things inefficiently. And if that is the case, elimination is a more useful skill than optimization. Even worse, people will occasionally fight to do things that waste time. “Why can’t you just come to the meeting? We have it every week.” Just because it is scheduled weekly does not mean it is necessary weekly. We do not have to agree to something just because it exists.

Saying no to superiors at work can be particularly difficult. One approach could be to remind superiors what we would be neglecting if we said yes and force them to grapple with the trade-off (Data/ description and its impact on ongoing work). For example, if the manager asks to do X, we can respond with “Yes, I’m happy to make this the priority. Which of these other projects should I deprioritize to pay attention to this new project?”

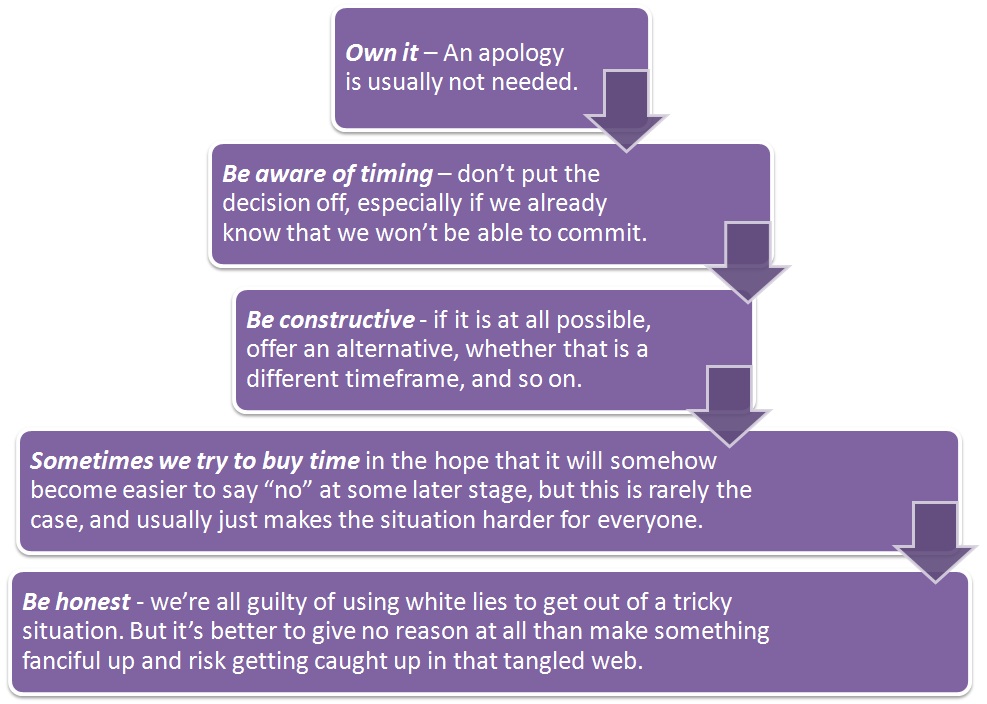

Pointers to be aware of when saying No

Content Curated By: Dr Shoury Kuttappa