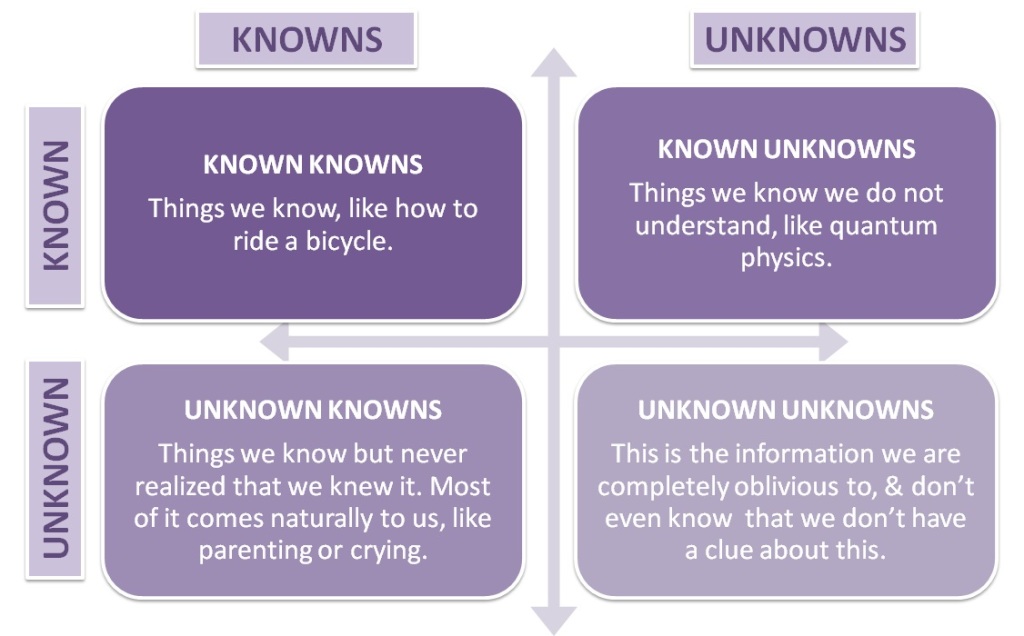

***Continued from Chapter 01 (Covered previously: Meaning & Interpretation, Historical Origins, Types Of Information: The Ignorance Of Ignorance, The Dunning-Kruger Effect In The Workplace and In Our Lives)

Link to Chapter 01:

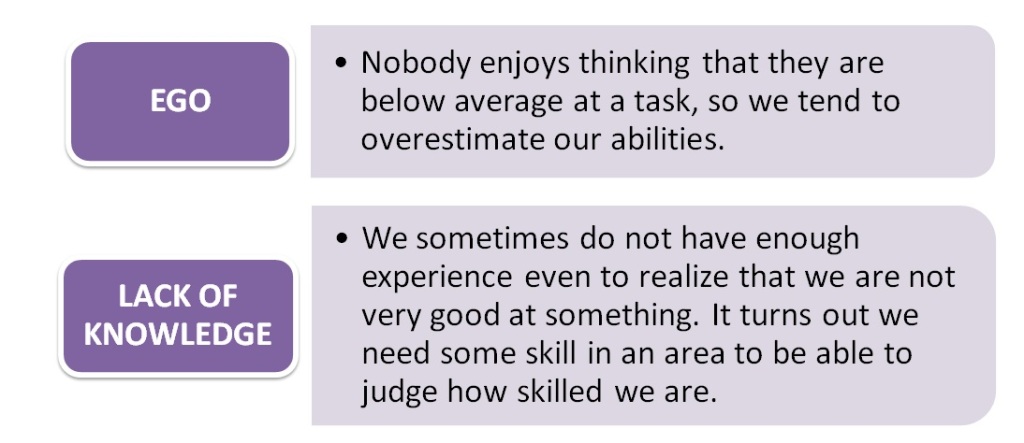

Behaviors That Initiate The Dunning-Kruger Effect

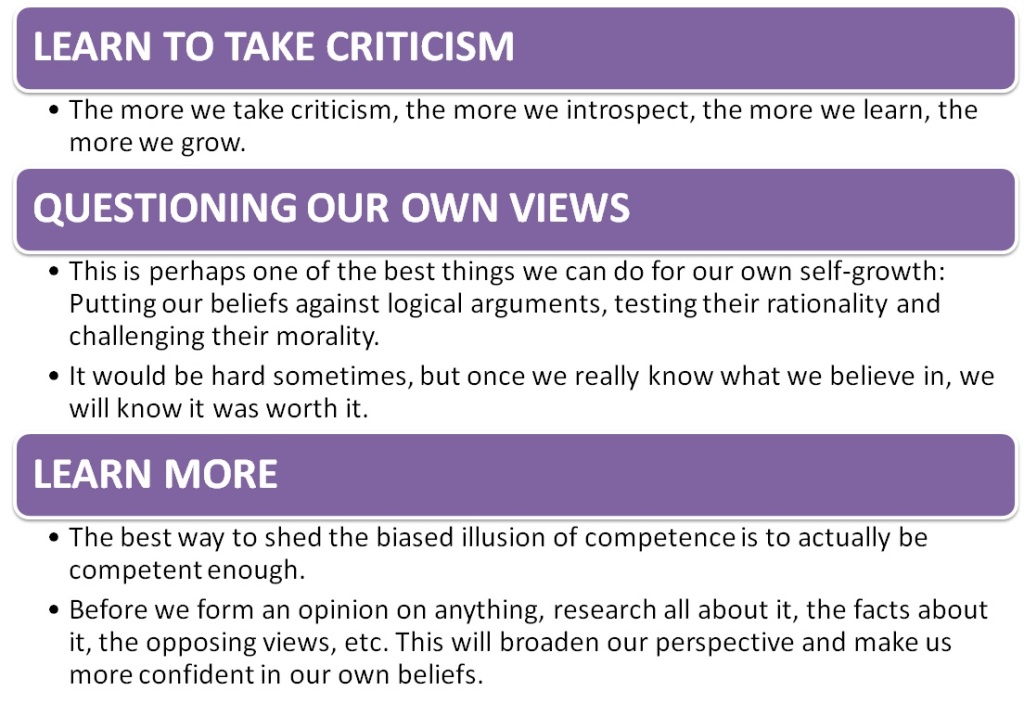

How To Steer Away From The Dunning Kruger Effect

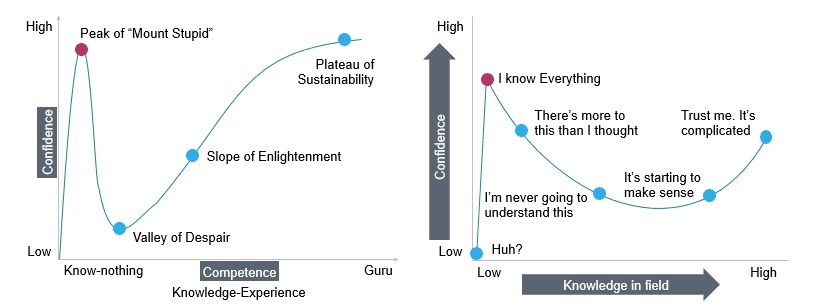

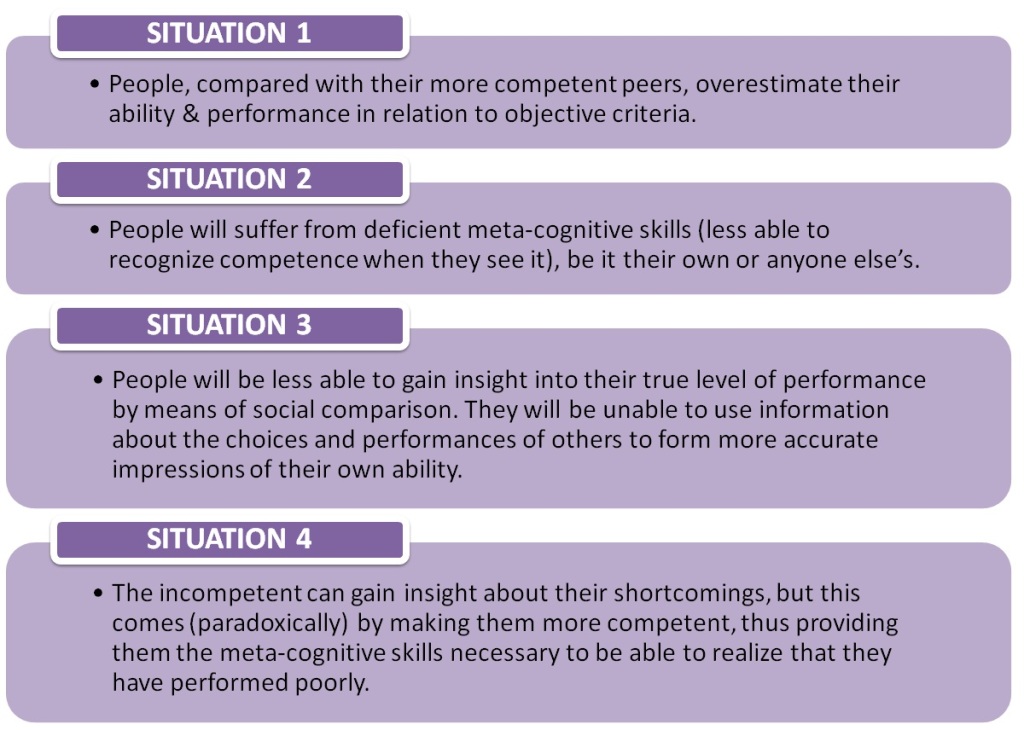

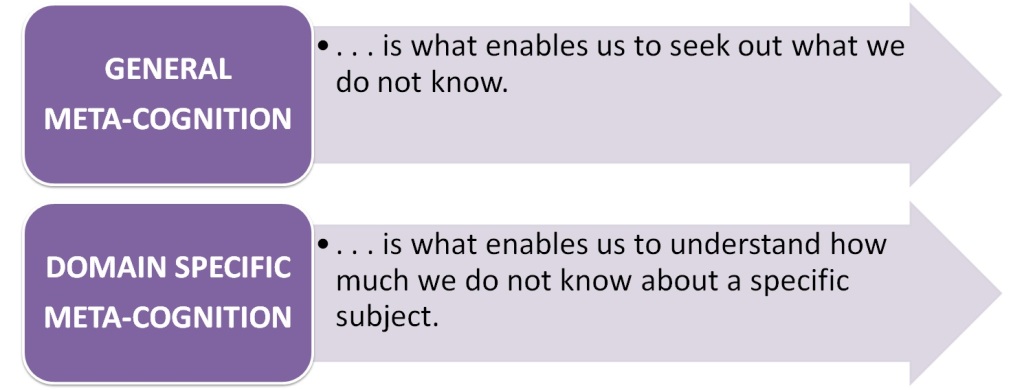

People can learn they are incompetent . . . by becoming competent. Thinking of meta-cognition again, we may divide it into two: General and domain specific.

If we can hone our general meta-cognition, we can ensure that we do not fall for the Dunning-Kruger effect in whatever domain. Every time we think – “I am above average, of course” – an alarm bell needs to go off in our mind. How do we know we are above average? Getting to know our peers and what they are doing can help. If we can distinguish between the competent and those who are not, maybe we do know what we are doing. If not, that should be enough of a warning to dive deeper into whatever we are learning – switching to specific meta-cognition.

Another antidote is the Stoic art of premeditatio malorum, or pre-meditation of evils. Assuming we have failed, or found out we are objectively bad at something – how do we tend to explain it? Would we call it just a bad day, or something deeper? Depending on how many times we face this failure in real life (a proxy for competence), the answer ought to transition from “just a bad day” to “I need to improve”. Here are a few other things we can do:

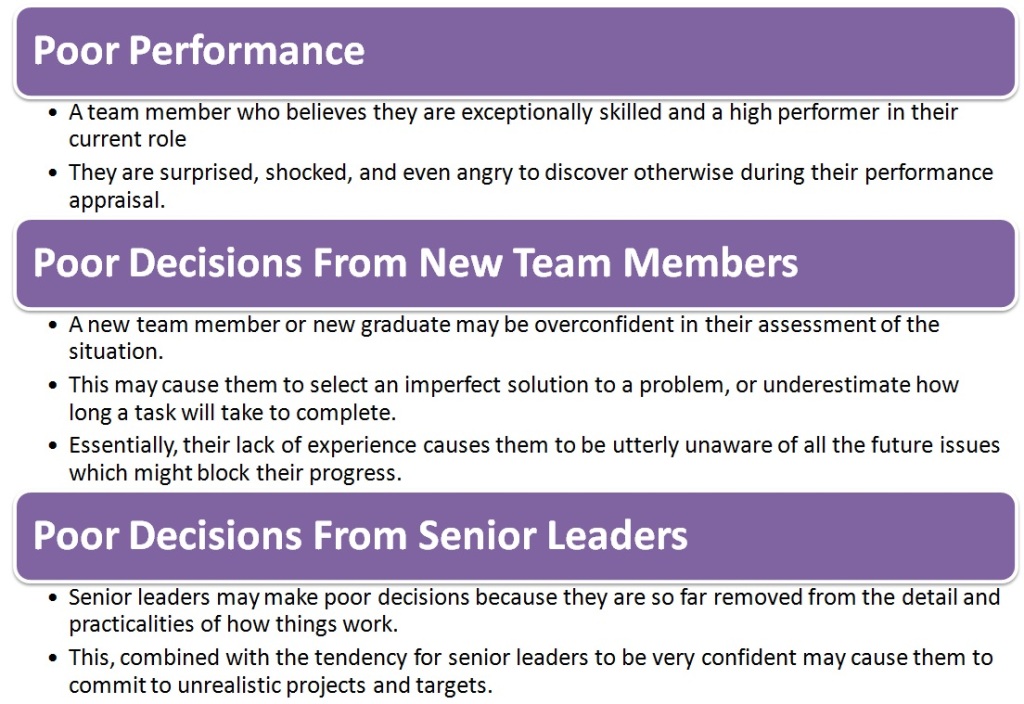

Countering The Dunning-Kruger Effect In The Workplace

People are social animals and do not like to be exposed as simply wrong, so the best way to handle people is to help them to understand that things are more complicated than they thought through their own reasoning. That is, they must realize for themselves that maybe there is more to the situation or problem than they initially thought. Some ways we can do this are:

A) With our Subordinates- Appropriate Coaching Style:

We can adopt a coaching style to give them feedback on their ideas and work progress. This style should not be critical but should help them to explore potential issues with their ideas. Over time, team members will develop a deeper understanding of typical issues that might arise, and a set of tools and strategies for analyzing situations for potential problems that might occur on their own.

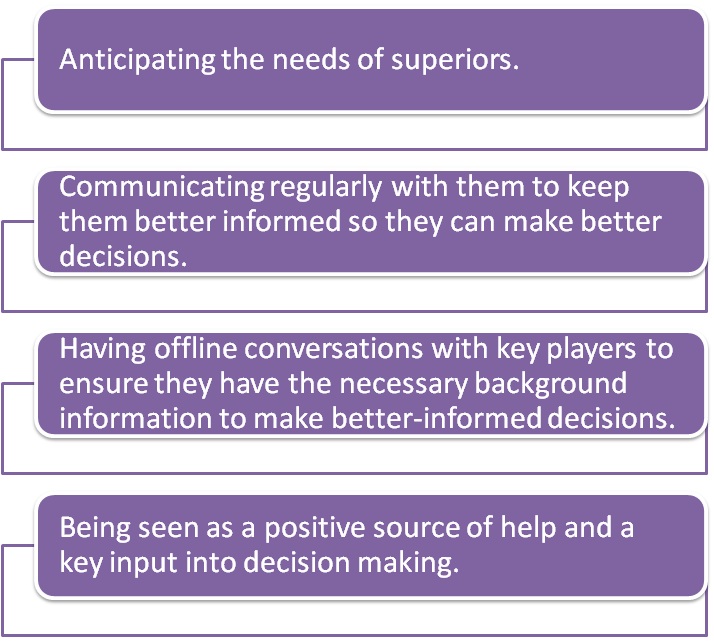

B) With our Superiors- Managing Up: We want our superiors to realize for themselves that their initial ideas may be more complex and fraught with difficulties than they originally imagined. This will involve:

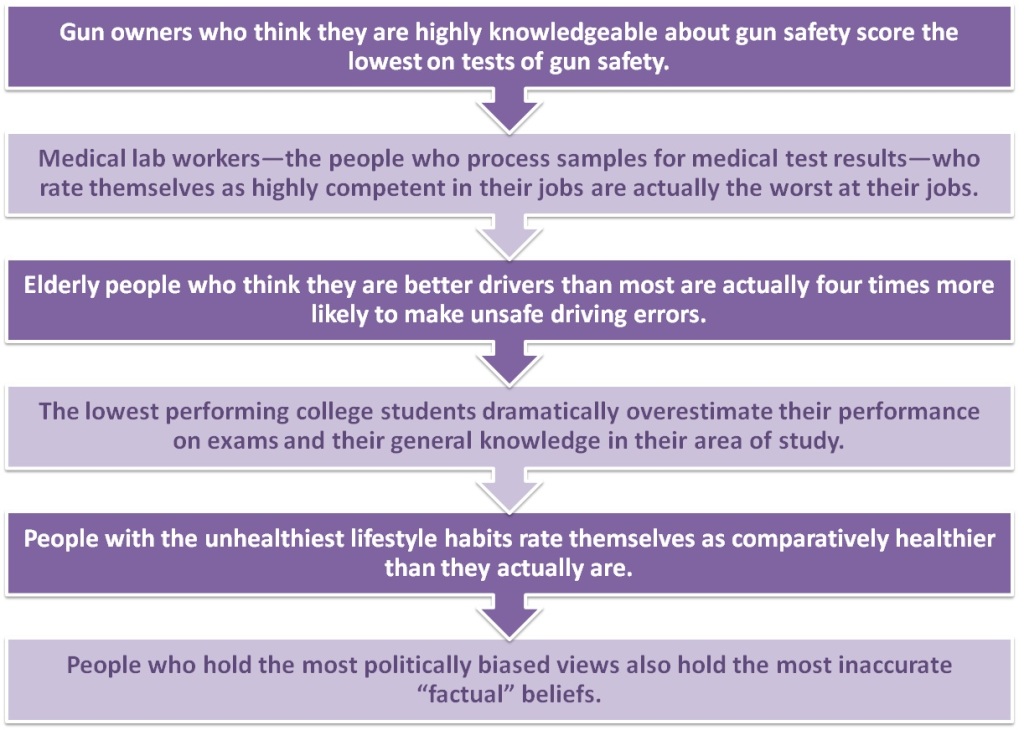

Domain Dependence Of The Dunning Kruger Effect

The effect does not show up everywhere. One big caveat is the domain under consideration. In some domains, knowledge does imply competence. For example, someone who understands inferential logic will be a competent logician. In other domains, competence depends on other factors too, like physical skill. For example, soccer coaches probably know what they are doing, but can we imagine Sir Alex Ferguson playing a 90 minute game now? He is not competent at playing soccer. Despite this, he has the knowledge to realize when one of his players is making a mistake in the game.

In domains where knowledge implies competence, lack of skill implies both the inability to perform competently as well as the inability to recognize competence, and thus are also the domains in which the incompetent are likely to be unaware of their lack of skill. Or, the domains in which the Dunning Kruger effect runs rabid. If we cannot serve in tennis, we probably don’t think we are Wimbledon material. But again, that does not stop some people from thinking they can win a point off Serena Williams.

Finally, in order for the incompetent to overestimate themselves, they must satisfy a minimal threshold of knowledge, theory, or experience that suggests to themselves that they can generate correct answers.

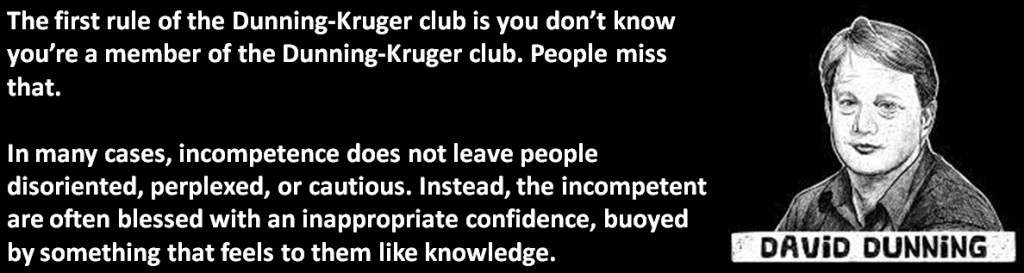

The Paradox Of Overcoming Ignorance

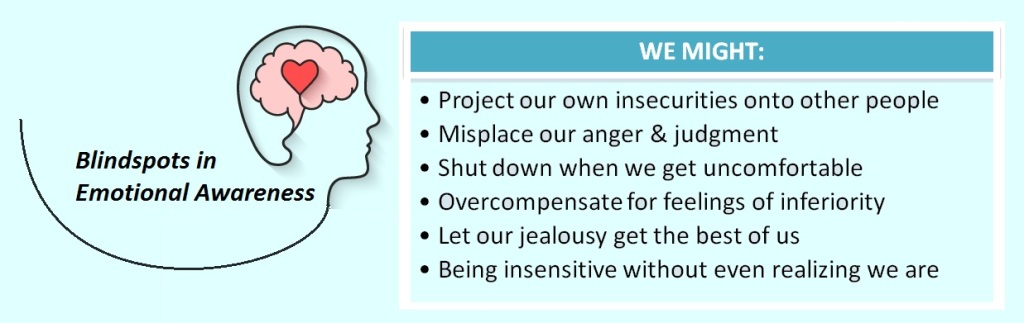

How do we get someone—or ourselves—to look for something we cannot even see? This is the paradox of trying to overcome our own ignorance: The very thing that would help us see our mistakes is the same thing that would keep us from making them in the first place. We cannot reason with a conspiracy theorist precisely because they did not form their beliefs with reason.

Part of the problem is that there is comfort in the feeling of knowing. People do not like uncertainty. And so settling on a belief helps us feel like we have made more sense of the world. When we can make sense of the world, we feel safe. Whether that belief is true or not does not matter—it just has to give us some relief from the anxiety of not knowing.

Also, it turns out it is not helpful to be direct with them for how stupid they are. Being too open to people simply causes them to become more defensive and double-down on their challenged beliefs, not relinquish them.

Conclusion

Humility is an important value. In fact, the Dunning-Kruger Effect suggests that humility can be highly practical. By intentionally underestimating our understanding of things, not only do we open up more opportunities to learn and grow, but we also foster a more realistic view of ourselves, and prevent ourselves from looking like a narcissist around others. Now, when we talk about the Dunning-Kruger effect we seem to (ironically enough) believe that it doesn’t apply to us. But the truth is, every single one of us has been a victim of it, at one point or the other, and our denial is the very proof it. We can find many examples of the Dunning-Kruger effect just by imploring ourselves, for example our shortcoming when it comes to accepting differing opinions or facts that directly contradict our views stems from our belief that we already know the “correct” opinion on a particular matter.

Content Curated By: Dr Shoury Kuttappa