Diwali, also known as the Festival of Lights, symbolizes the spiritual “victory of light over darkness, good over evil, and knowledge over ignorance”. Celebrations are wonderful ways in which our deep physical, social and psychological needs are met. The family is an important institution that plays a crucial role in the lives of most Indians. In this era of nuclear families, where we experience clashes and misunderstanding on multiple occasions, the survival and dignified growth of family relationships becomes a concern.

Diwali & The Four Life Stages – Varnashrama Dharma

Diwali is not only a festival of lights but also the festival of family relations and celebration. In Ancient India, for the optimum fulfilment, satisfaction and peace in one’s life, the stages of life were discussed as the ‘ashramas’ or ‘Varnashrama Dharma’.

The Varnashrama Dharma system consists of four age-based life stages discussed in Indian texts of the ancient and medieval eras. The child begins his or her life with Brahmacharya stage as a student, then progresses to the Grihastha stage of a householder, then retires to Vanaprastha stage and finally accepts the Sanyasa stage of renunciation.

The Grihastha Ashrama stage (after the marriage of an individual) is considered the most important of all stages in the social, cultural and economic context, as human beings not only pursued a virtuous life, they produced food and wealth that sustained people in other stages of life, as well as, the offspring, that continued mankind. This stage is also where the most intense physical, sexual, emotional, occupational, social and material attachments exist in a human beings life.

Almost all the festivals in India are concentrated around this concept of celebration with family and friends. However, Diwali celebrates the Grihastha stage to the fullest sense by focusing on the multiple aspects and qualities of it, highlighting the need to enjoy and appreciate each member of the family with deserving importance and their mutual bonding with other members of the family. It is almost a complete compendium of coordination of members of family, respect towards each other, love, affection, care and sharing, human values of forgiving, gratitude and humility.

Diwali helps us to seamlessly transmit family values and find our place in the circle of life. Coming together to celebrate a festive occasion reinforces family relationships, provides ample opportunities for bonding and nourishes emotional attachments. Happy memories become positive inner resources that help to calm the mind – they release the feel-good chemicals in the brain. Creating happy memories helps us remember the good times more than the bad ones.

The Bowen Family Systems Theory

The Bowen family systems theory was developed by psychiatrist and researcher Dr Murray Bowen (1913–90). In recent years Bowen’s concept of ‘differentiation of self’ — which describes differing levels of maturity in relationships — has been shown by researchers to be related to important areas of well-being, including marital fulfilment, and the capacity to handle stress, make decisions and manage social anxiety.

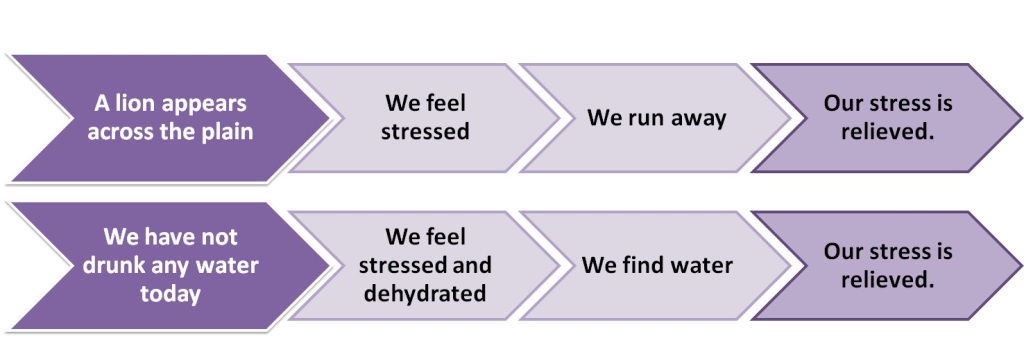

Bowen’s theory lends a perspective to understand the variations in how different people manage similarly stressful circumstances. The theory looks at our personal and relationship problems as coming from exaggerated responses, to sensing a threat to family harmony and that of other groups. Some examples from daily life:

Bowen’s concept of ‘differentiation of self’ forms the basis of a systems understanding of maturity. The concept of differentiation refers to the ability to think as an individual while staying meaningfully connected to others. It describes the varying capacity each person has to balance their emotions and their intellect, and to balance their need to be attached with their need to be a separate self. The best way to grow a more solid self was in the relationships that make up our original families; running away from difficult family members would only add to the challenges in managing relationship upsets.

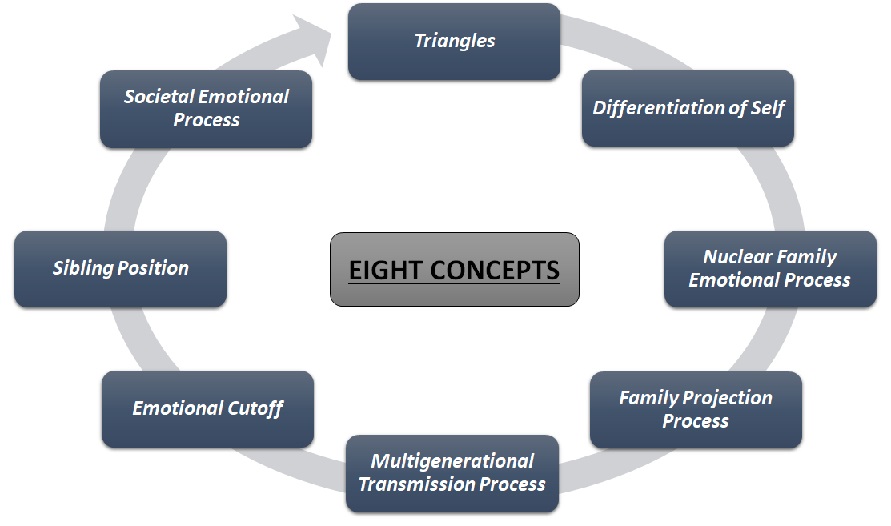

The Eight Concepts

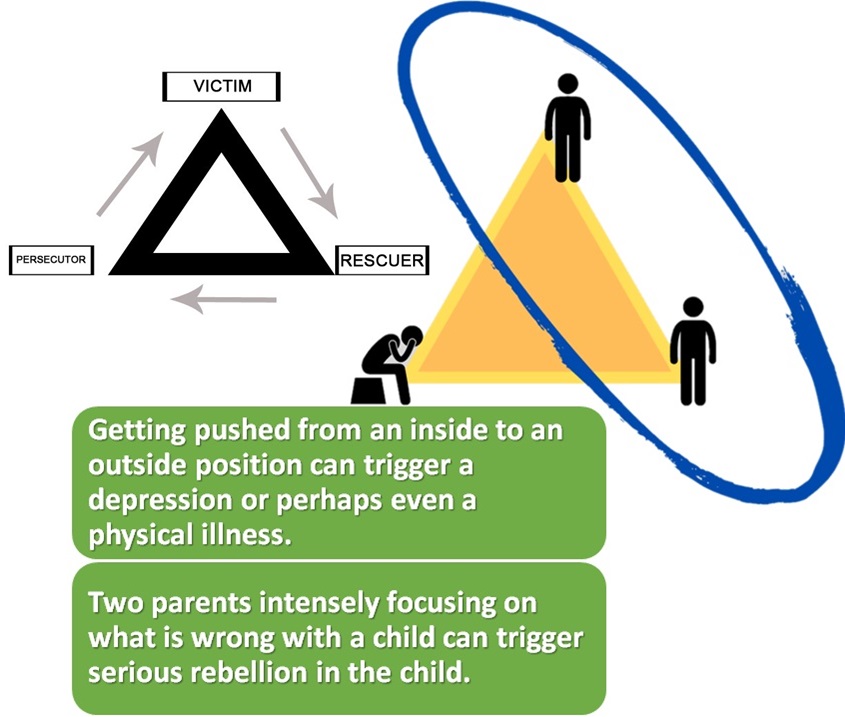

01: Triangles

A triangle is a three-person relationship system. It is considered the building block or “molecule” of larger emotional systems because a triangle is the smallest stable relationship system. A two-person system is unstable because it tolerates little tension before involving a third person. A triangle can contain much more tension without involving another person because the tension can shift around three relationships. If the tension is too high for one triangle to contain, it spreads to a series of “interlocking” triangles. Spreading the tension can stabilize a system, but nothing gets resolved.

A triangle creates an odd man out, which can be a difficult position for individuals to tolerate. Anxiety generated by anticipating, being, or by being the odd man out is a potent force in triangles. The patterns in a triangle change with increasing tension. In calm periods, two people are comfortably close “insiders” and the third person is an uncomfortable “outsider.” The insiders actively exclude the outsider, and the outsider works to get closer to one of them. Someone is always uncomfortable in a triangle and pushing for change. The insiders solidify their bond by choosing each other in preference to the less desirable outsider.

People’s actions in a triangle reflect their efforts to assure their emotional attachments to important others, their reactions to too much intensity in the attachments, and their taking sides in others’ conflicts. When someone chooses another person over oneself, it arouses particularly intense feelings of rejection. If mild to moderate tension develops between the insiders, the most uncomfortable one will move closer to the outsider. One of the original insiders now becomes the new outsider and the original outsider is now an insider.

At a high level of tension, the outside position becomes the most desirable. If severe conflict erupts between the insiders, one insider opts for the outside position by getting the current outsider fighting with the other insider. If the manoeuvring insider is successful, he gains the more comfortable position of watching the other two people fight. When the tension and conflict subside, the outsider will try to regain an inside position.

Examples:

02: Differentiation of Self

Families and other social groups tremendously affect how people think, feel, and act, but individuals vary in their susceptibility to a “groupthink” and groups vary in the amount of pressure they exert for conformity. These differences between individuals and between groups reflect differences in people’s levels of differentiation of self. The less developed a person’s “self,” the more impact others have on her/his functioning and the more she/he tries to control, actively or passively, the functioning of others.

The basic building blocks of a “self” are inborn, but an individual’s family relationships during childhood and adolescence primarily determine how much “self” he develops. Once established, the level of “self” rarely changes unless a person makes a structured and long-term effort to change it.

People with a poorly differentiated “self” depend so heavily on the acceptance and approval of others that either they quickly adjust what they think, say, and do to please others or they dogmatically proclaim what others should be like and pressure them to conform. An extreme rebel is a poorly differentiated person too, but she/he pretends to be a “self” by routinely opposing the positions of others.

People with a well-differentiated “self” are able to recognize their realistic dependence on others, and can stay calm and clear headed enough in the face of conflict, criticism, and rejection. They can distinguish thinking rooted in a careful assessment of the facts, from thinking clouded by emotionality. Thoughtfully acquired principles help guide decision-making about important family and social issues, making them less at the mercy of the feelings of the moment. What they decide and what they say matches what they do. They can act selflessly, but their acting in the best interests of the group is a thoughtful choice, not a response to relationship pressures.

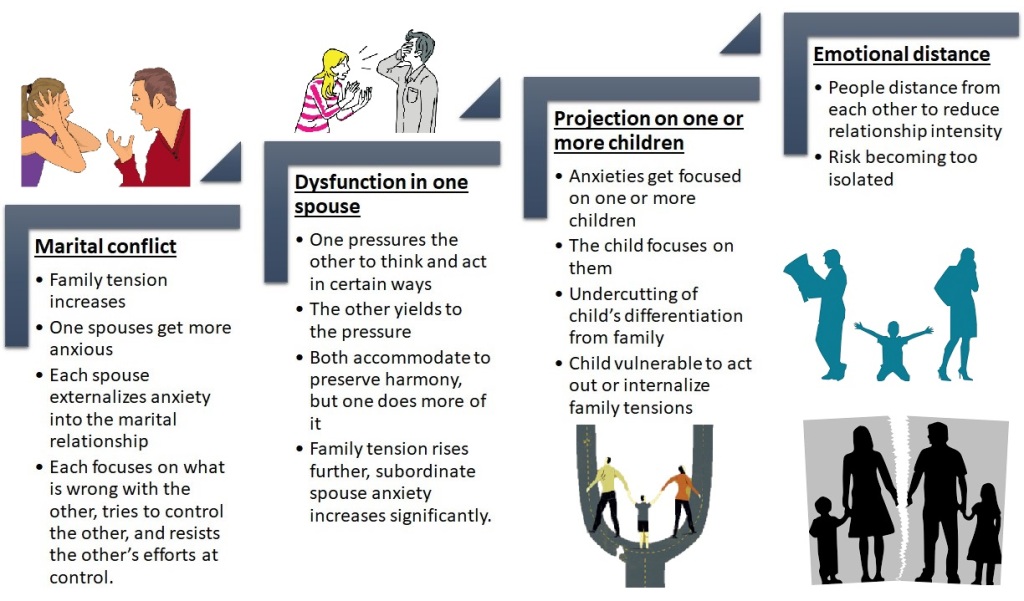

03: Nuclear Family Emotional Process

The concept of the nuclear family emotional system describes four basic relationship patterns that govern where problems develop in a family. The forces primarily driving them are part of the emotional system. The tension level depends on the stress a family encounters, how a family adapts to stress, and on a family’s connection with extended family and social networks. Tension increases the activity of one or more of the four relationship patterns. Where symptoms develop depends on which patterns are most active. The four basic relationship patterns are:

The more anxiety one person or one relationship absorbs, the less other people must absorb. This means that some family members maintain their functioning at the expense of others. People do not want to hurt each other, but when anxiety chronically dictates behaviour, someone usually suffers for it.

***To be continued in Chapter 02 (Points 04 to 08) Link to Chapter -02:

Content Curated By: Dr Shoury Kuttappa