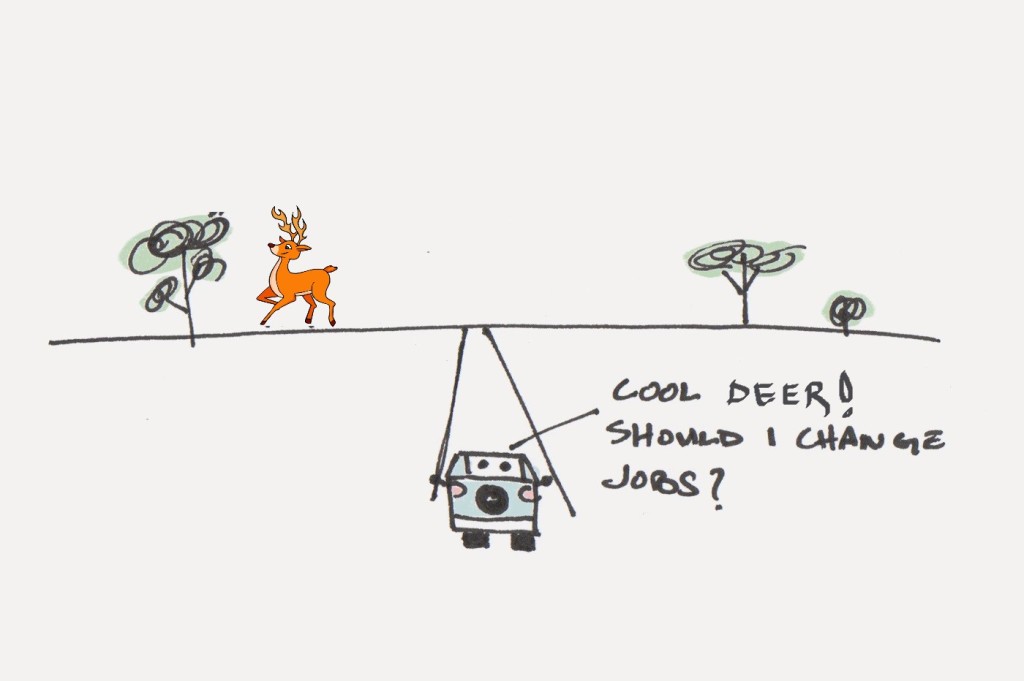

A deer may be startled by a loud noise and take off through the forest, but as soon as the threat is gone, the deer immediately calms down and starts grazing. And it does not appear to be in anxiety about it later. Let us play act for a moment that we are that deer, living in the grasslands of India. We have slim long feet that help us get into a sprint quickly and pruned senses that pick up signs of danger, a majestic antelope that grabs attention from the group of humans that, every now and then, come driving around on a jungle expedition taking pictures of us.

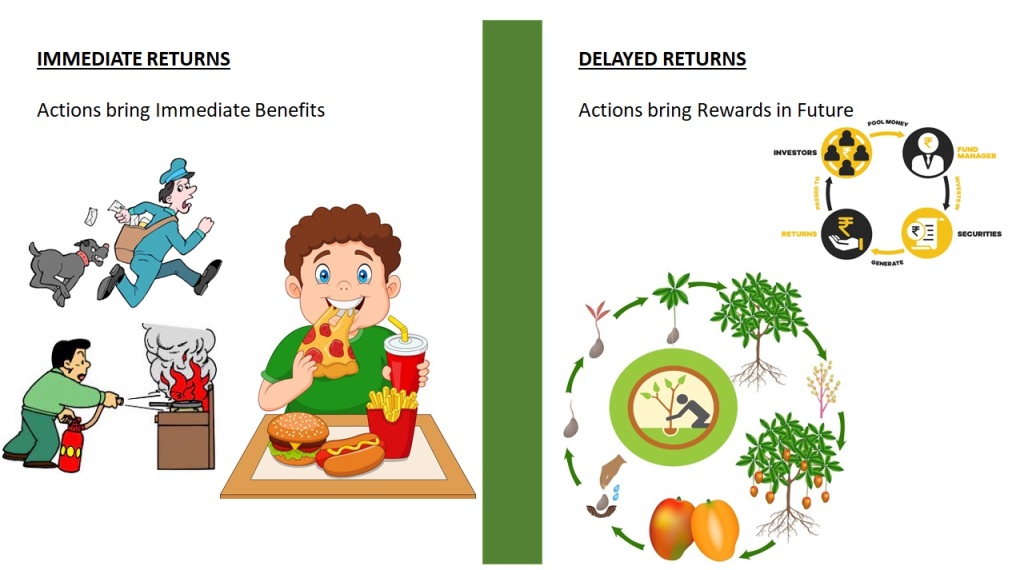

Perhaps the biggest difference between us and our other deer friends, and the humans taking our photograph is that nearly every decision we make (as a deer) provides an immediate benefit to our life. When we are hungry, we walk over and chomp on a bush. When it rains, we shelter under a tree. When we spot a tiger, we run away. Most of our choices as a deer—like what to eat or where to sleep or when to avoid a predator—make an immediate impact on our life. We live in what scientists call an immediate-return environment because our actions instantly deliver clear and immediate outcomes.

Now, let’s flip the script and pretend we are one of the humans on the jungle expedition. While taking photographs from the Jeep, we might think, “This safari has been a lot of fun. It would be cool to work as a park ranger and see deer every day. Speaking of work, is it time for a career change? Am I really doing the work I was meant to do? Should I change jobs?”

Most of the choices we make today will not benefit us immediately. If we do a good job at work today, we will get recognition at the end of the business quarter. If we save money now, we will have enough for retirement later. Many aspects of modern society are designed to delay rewards until some point in the future. This is true of our problems as well. Such a situation is commonly referred to as delayed returns.

Researching hunting and gathering societies, anthropologist James Woodburn classified societies into two major categories: those with immediate return systems and those with delayed return systems. This entails two different environments.

The Immediate Return Environment

In an Immediate Return Environment, the actions of an individual bring about immediate benefits. Everything that prehistoric humans did was oriented at the present, as a result of following their instincts to survive: avoiding predators, finding shelter when they need it, reproducing, hunting and gathering to survive. For the sole purpose of completing these tasks, they made tools and weapons that did not require a lot of labour. The human brain evolved in this type of environment to use anxiety to protect humans from danger and starvation, compelling them to solve all the short-term problems they were faced with. The feelings of stress and anxiety were relieved as each problem was solved.

The Delayed Return Environment

The actions taken in a Delayed Return Environment are not directed at an immediate benefit, but with future reward in mind. Each day we work, we are putting in the effort to get a reward in the future: salary at the end of the month/project. We study in order to obtain a degree in years. We save money so we can invest it or enjoy spending it later. We choose healthy foods and exercise knowing that it will not make us fit immediately, but in the future and only if we maintain a regimen, and so on.

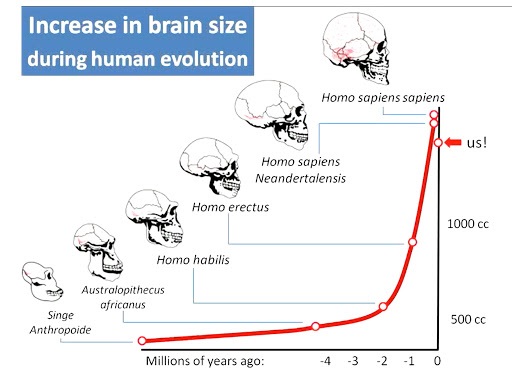

As humans evolved, they adopted more characteristics of delayed return societies, making elaborate weapons, processing, and storing food for future use, etc. But the modern environment presents a very abrupt change when you look at it from the perspective of evolution. The Delayed Return Environment tends to lead to chronic stress and anxiety for humans. Why? Because the human brain did not evolve for life in a delayed-return environment.

Evolution of the Brain

The earliest remains of modern humans, known as Homo sapiens, are approximately two hundred thousand years old. These were the first humans to have a brain relatively like ours. In particular, the neocortex—the newest part of the brain and the region responsible for higher functions like language—was roughly the same size two hundred thousand years ago as today. Compared to the age of the brain, modern society is incredibly new. It is only recently—during the last 500 years or so—that our society has shifted to a predominantly Delayed Return Environment.

The pace of change has increased exponentially compared to prehistoric times. In the last 100 years we have seen the rise of the car, the airplane, the television, the personal computer, the Internet, and MTV. Nearly everything that makes up our daily life has been created in a very small window of time. From the perspective of evolution, however, 100 years is nothing. The modern human brain spent hundreds of thousands of years evolving for one type of environment (immediate returns) and in the blink of an eye the entire environment changed (delayed returns).

The Evolution of Anxiety

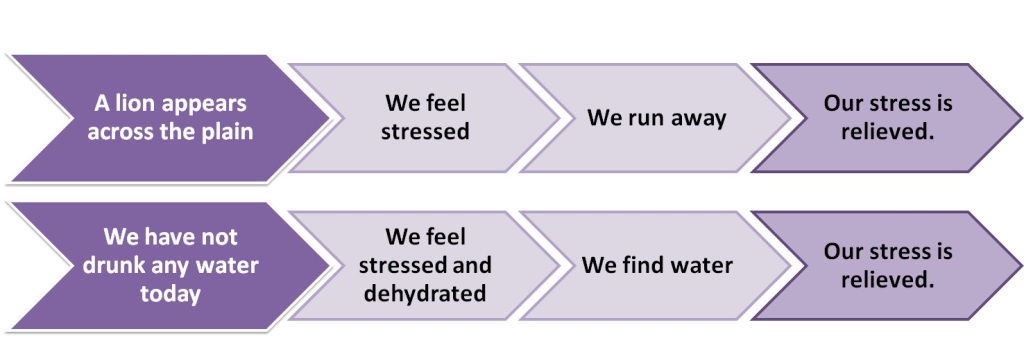

The mismatch between our old brain and our new environment has a significant impact on the amount of chronic stress and anxiety we experience today. Thousands of years ago, when humans lived in an Immediate Return Environment, stress and anxiety were useful emotions because they helped us take action in the face of immediate problems. For Instance:

Anxiety was an emotion that helped protect humans in an Immediate Return Environment. It was built for solving short-term, acute problems. There was no such thing as chronic stress because there are no really chronic problems in an Immediate Return Environment. Wild animals rarely experience chronic stress. Today we face different problems. Will I have enough money to pay the bills next month? Will I get the promotion at work or remain stuck in my current job? Will I repair my broken relationship? Problems in a Delayed Return Environment can rarely be solved right now in the present moment.

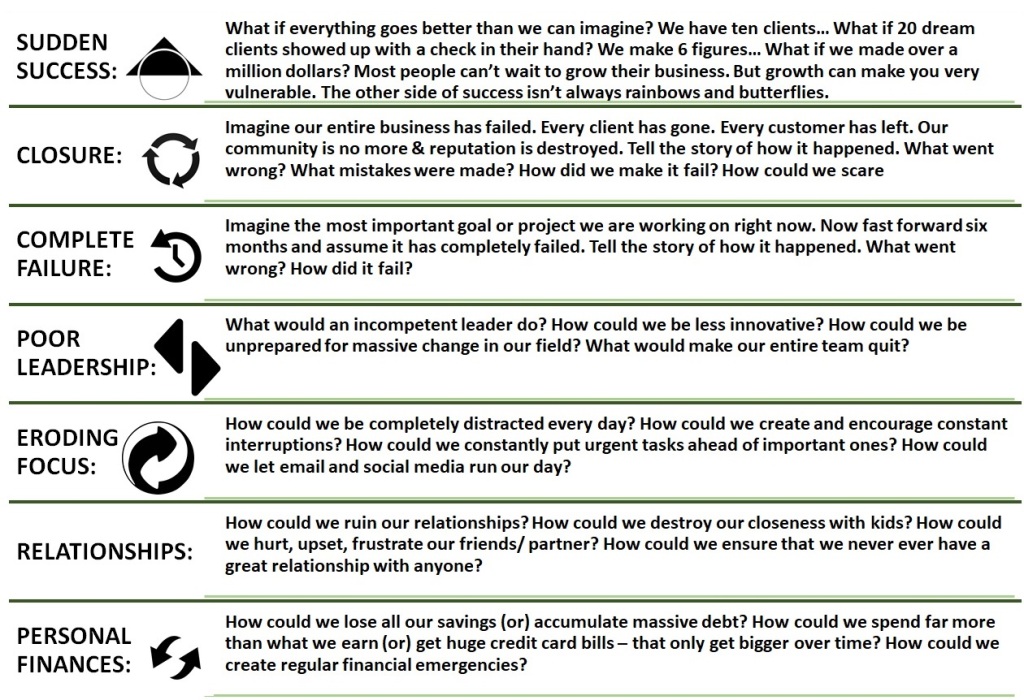

Ways to balance our Anxiety and Stress.

One of the greatest sources of anxiety in a Delayed Return Environment is the constant uncertainty. There is no guarantee that working hard in school will get you a job. There is no promise that investments will go up in the future. There is no assurance that going on a date will land you a soul mate. Living in a Delayed Return Environment means you are surrounded by uncertainty. So how do we reconcile the way our brains work with the problems of the Delayed Return Environment?

First things first: we need to deal with the built-up chronic stress through small lifestyle changes. Many of us have excess levels of cortisol (the stress hormone) because of this fast-paced environment, so adjusting our diet, sleeping habits, and exercising more is the first step to balancing these hormones. Of course, practices such as meditation can help us regain emotional balance and realign our thoughts; meditation takes time to perfect, but it is worth it (there we go, delayed return all over again).

Next, there are two ways to regain balance:

01) Measuring something:-> We cannot know for certain how much money we will have in retirement, but we can remove some uncertainty from the situation by measuring how much we save each month. We cannot predict when we will find love, but we can pay attention to how many times we introduce ourselves to someone new.

The act of measurement takes an unknown quantity and makes it known. When we measure something, we immediately become more certain about the situation. Measurement will not magically solve our problems, but it will clarify the situation, pull us out of the black box of worry and uncertainty, and help us get a grip on what is actually happening.

Furthermore, one of the most important distinctions between an Immediate Return Environment and a Delayed Return Environment is rapid feedback. Animals are constantly getting feedback about the things that cause them stress. As a result, they actually know whether or not they should feel stressed. Without measurement you have no feedback.

02) Shift Your Worry:-> The second thing we can do is “shift our worry” from the long-term problem to a daily routine that will solve that problem. Instead of worrying about living longer, we can focus on taking a walk each day. Instead of worrying about losing enough weight for the wedding, we can focus on cooking a healthy dinner tonight.

The key insight that makes this strategy work is making sure our daily routine both rewards us right away (immediate return) and resolves our future problems (delayed return).

In the end, hopefully, by reflecting on the way the brain works and acknowledging how it puts anxiety in motion, we can use these mechanisms to our advantage. The Delayed Return Environment presents a challenge for humans, but there is a way to reconcile the age-old hardwiring of the brain with this environment that presents itself as threatening. Research has shown that the ability to delay gratification is one of the primary drivers of success. It is then interesting that delaying gratification is both the opposite of what our brain evolved to do and the skill that matches the Delayed Return Environment we live in today.

Content Curated By: Dr Shoury Kuttappa.