A debate about hiring for attitude versus aptitude has developed over the years. Nearly every job posting includes the type of experience an employer is seeking, which makes sense considering that companies want to locate applicants who have already demonstrated a certain level of skill in that particular industry or role.

Both the experience (hard skills) and the attitude (soft skills) are given high priority in the initial job requirements. The debate comes to light during the interview and hiring process.

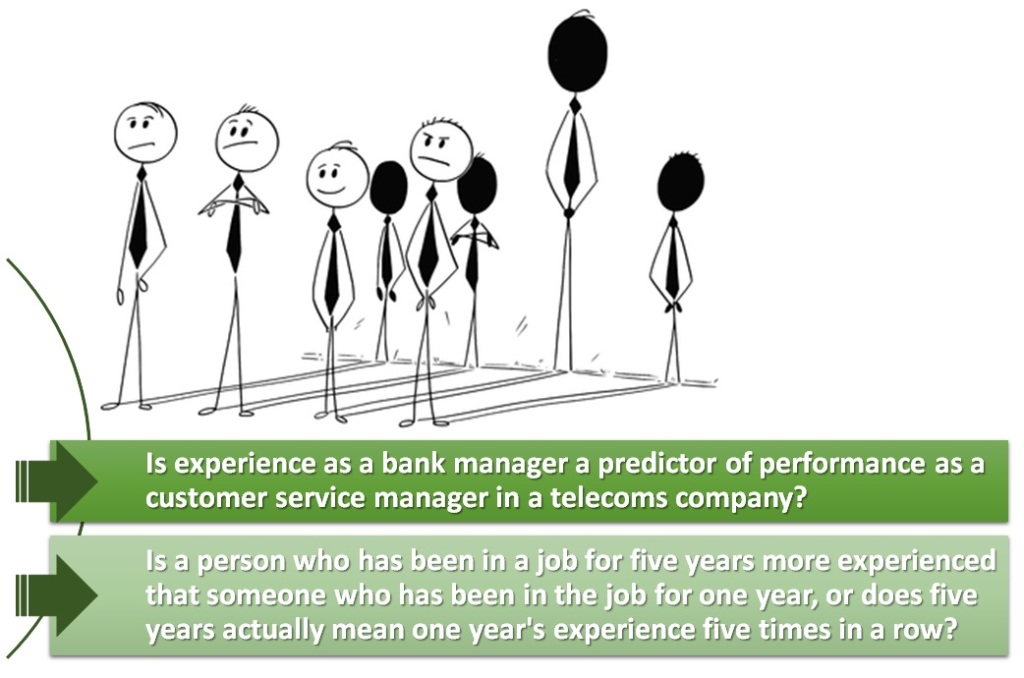

Although the initial requirements highlight soft skills and personality traits as important parts of the job applicant’s qualifications, during interviews, many hiring managers focus on hard skills and experience because they are easier to discuss and judge. As a result, many applicants end up being hired based exclusively on their experience rather than on their attitude. Is it better to hire people on the basis of their experience or their potential? If we believe experience is preferable, and that age equates with experience, there’s no better time than now. But experience is not the issue. The question is, experience of what?

The problem of hiring on the basis of experience gained in a former job is the assumption that it parallels what is needed in the new job. Organisational cultures and situations can and do differ dramatically. There is a litany of highly competent executives like Bob Nardelli, who excelled at GE, but was unable to duplicate that success at Home Depot. Experience is situation-specific.

Experience vs Potential

Experience also tends to equate with baggage. Behaviour is learned. We do what we do on the basis of it having led to success in the past. We’ve all been annoyed by people who insist on telling us how things were done in their last company or last job. There are benefits to learning how other people do things, but the underlying message is that what we’re doing is no good, and that can be demoralising.

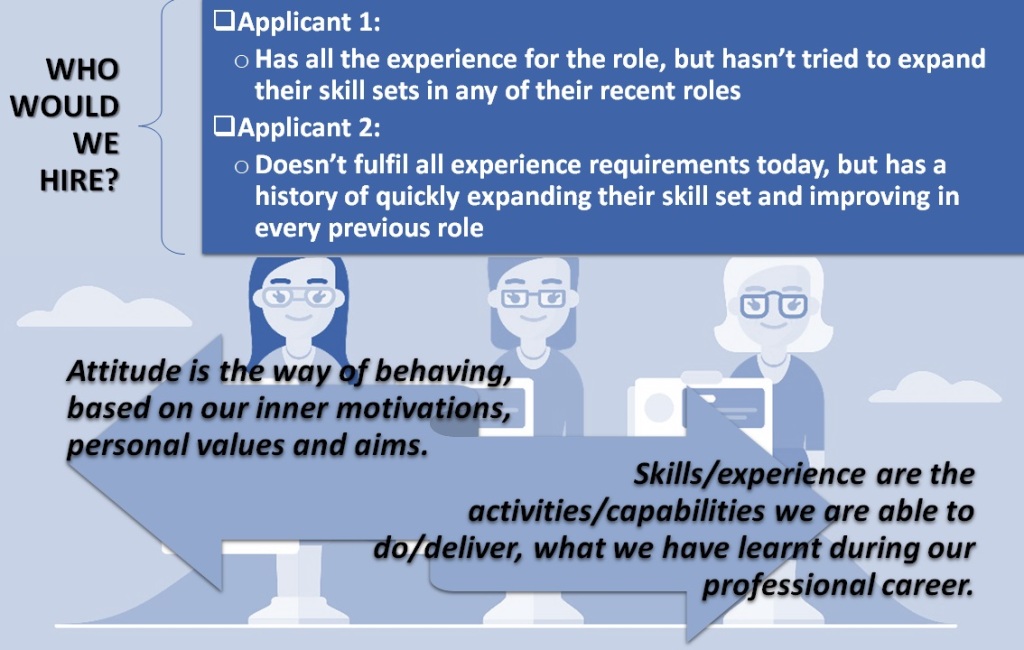

So what about hiring on potential? This, too, comes with some small print. “Potential”, may also get translated as “lack of directly applicable experience”. That means giving the individual time to learn, which implies training, coaching and the provision of development opportunities. This one of the reasons many companies fall back on what they hope is the quicker-fix solution of hiring so-called experienced people — it takes less effort.

There are a number of companies that have successfully hired for potential though, notably Southwest Airlines, the originator of the discount airline model. Southwest claims it hires for “attitude” — motivation, energy, keenness, and team spirit. But Southwest doesn’t make the mistake of thinking that’s enough. It follows up with intensive skills and culture training. People learn what behaviour is acceptable and rewarded. Very few organisations make a conscious effort to do this. Instead, people have to learn the hard way.

If we wish to hire people for their potential, we need to define the core competencies for the roles in question. These are things like a demonstrated ability to motivate people, being able to close sales, a record of building effective teams, or being able to make and stand by hard decisions. Either people have done these things or they haven’t. They can be tested and observed. Assessing potential doesn’t have to be subjective — it manifests itself in observable behaviour.

But as James Callaghan, a former British Prime Minister, once said: “Some people, however long their experience or strong their intellect, are temperamentally incapable of reaching firm decisions.” No amount of experience can change that.

What gets us Hired – Attitude or experience?

For recruiters, the longstanding question remains – who makes for a better hire – someone with the perfect experience, or someone with the right attitude?

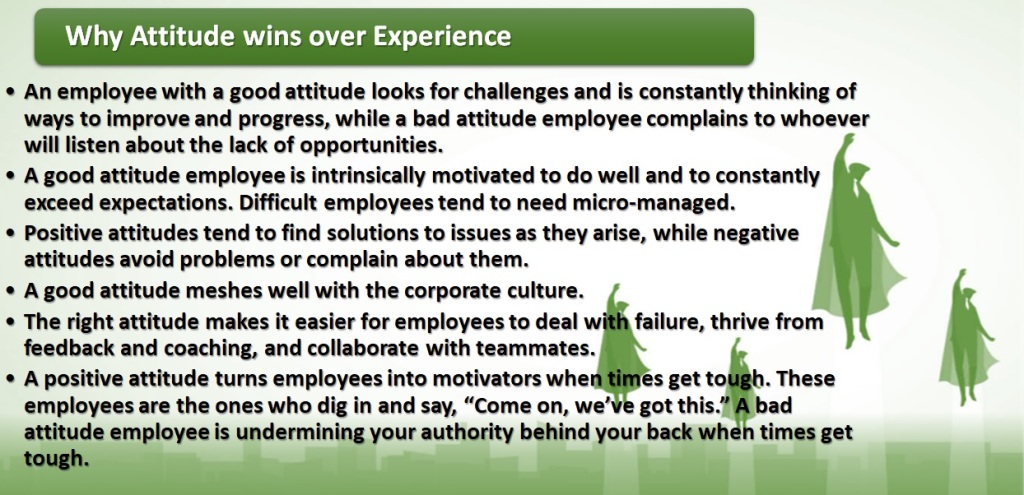

A positive attitude can transform a workplace. Employers value a positive attitude because of the impact it can have. It’s important to remember that any role – no matter how big or small – gives an opportunity to make a positive impact through the way we work. Employers are looking for people who add to the culture. Workplace culture is important to employers, and the benefits we bring to the collective culture often matter more than our experience and qualifications. The good news is that means there’s more flexibility in how we present ourselves during a job search. If employers can’t imagine sitting beside us and working on a project, then it’s really hard to get hired. So if we don’t show our personality, then it’s difficult for them to choose us over somebody who’s got the same qualifications or experience.

Exhibiting a great attitude at Work

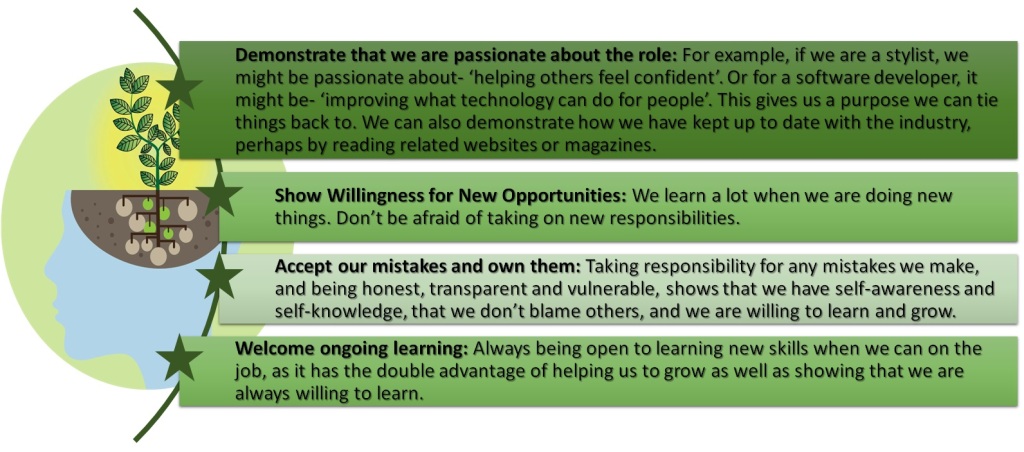

It’s not always easy to show employers how we think, but a great attitude can go a long way. Some ways in which we can show this are:

Knowing how to show our enthusiasm to employers can make a huge difference to whether we are considered for a role. A great attitude can help us stand out – even if we are up against others who may be more qualified or experienced.

Hiring for Attitude

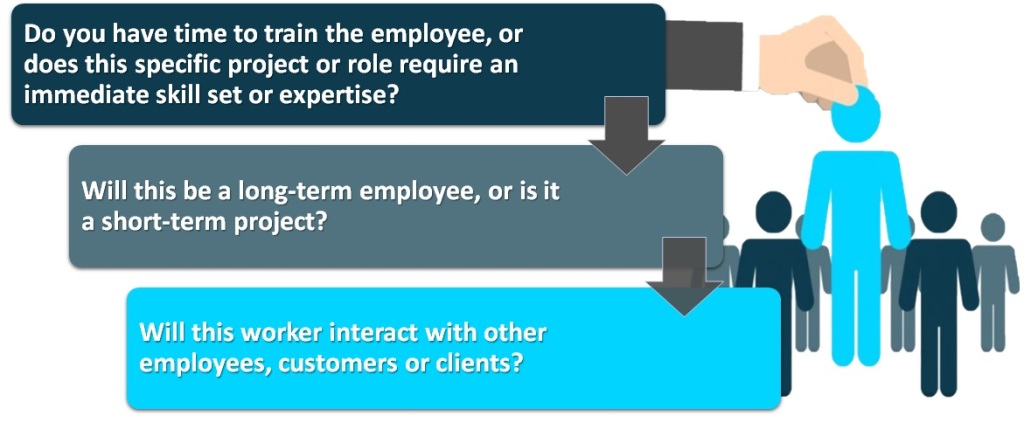

Although it’s clear that attitude should play a major role in the hiring process, there may be some instances when skills and experience really are of utmost importance. In that case, we may want to consider hiring freelancers to design websites, or to create content or code, for example. Here are a few questions we can raise when determining whether attitude or skill set may be more important:

Although this isn’t a comprehensive list, these questions can help to determine what to evaluate during the hiring process. Certain ways in which we can evaluate job applicants’ attitudes during the hiring process may be:

A) Ascertaining what type of attitude is needed for the job. Different attitudes are better suited for particular roles and teams, so it’s important to clearly identify what type of employee attitude is needed for the specific position you are hiring for. For example, when hiring for a sales role, you might want an employee who is charismatic and doesn’t take no for an answer. However, this type of attitude may not be necessary for a graphic design role.

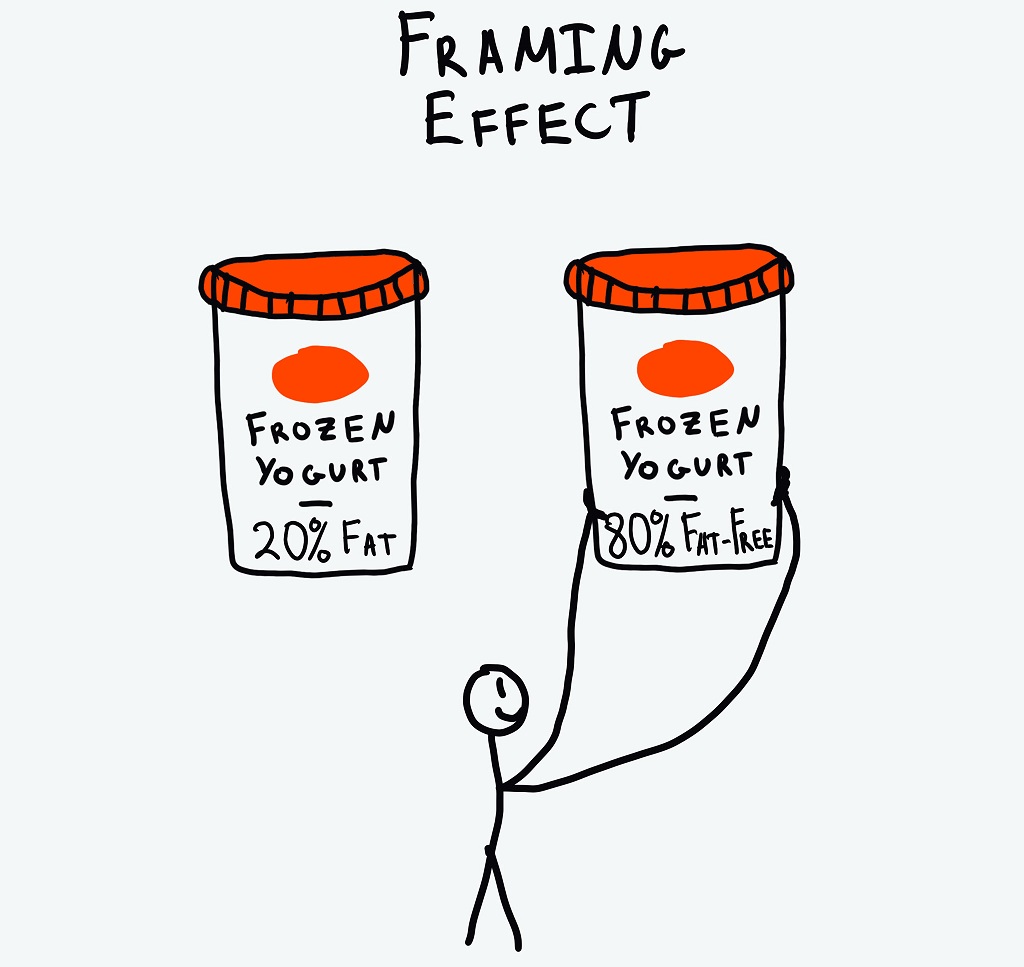

B) Posing questions that reveal attitude. It can be helpful to ask questions like, “Can you tell me about a time you failed?” But instead of focusing on the specific details of their failure, listen to how they frame their response. Do they take ownership of the failure and show a growth mentality, or do they blame others and speak bitterly?

C) Solicit Assistance from our Team. We can get a more holistic view of someone’s attitude by having multiple people assess it. For example, how did they treat the receptionist when they checked in? We can also give the candidate a tour of our office so they can meet other employees, or have select employees sit in on an interview, to assess whether the candidate is a good fit for the company culture.

D) Favouring Internal Promotions & Employee Referrals. It is easier to understand an employee’s attitude if they already work for you. Instead of taking a risk on a new hire, it may be helpful to promote from within your company. Employee referrals are also a great way to gather insight on candidates’ attitudes.

Content Curated By: Dr Shoury Kuttappa