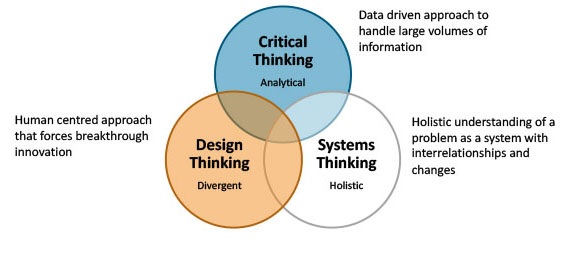

Organizational development “refers to the context, focus and purpose of the change while developing an organization.” Additionally, one recent definition of organizational development states: “Organizational development is a critical and science-based process that helps organizations build their capacity to change and achieve greater effectiveness by developing, improving, and reinforcing strategies, structures, and processes.” In essence, good organizational change and development require a systems-thinking mindset and an interdisciplinary, holistic approach to tackling complex organizational challenges.

Systems Thinking has been gaining significant interest lately as a comprehensive approach to introducing organizational change and development. Through systems thinking, a number of core concepts and practical tools can be applied to better understand the complexity of each organization. There are many competing definitions of systems thinking in the academic literature. As Ross D. Arnold and Jon P. Wade point out in their recent article, “Systems thinking is, literally, a system of thinking about systems.”

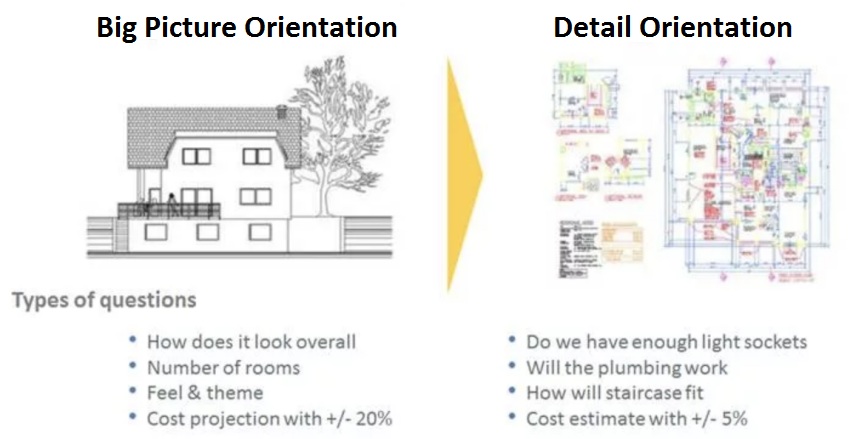

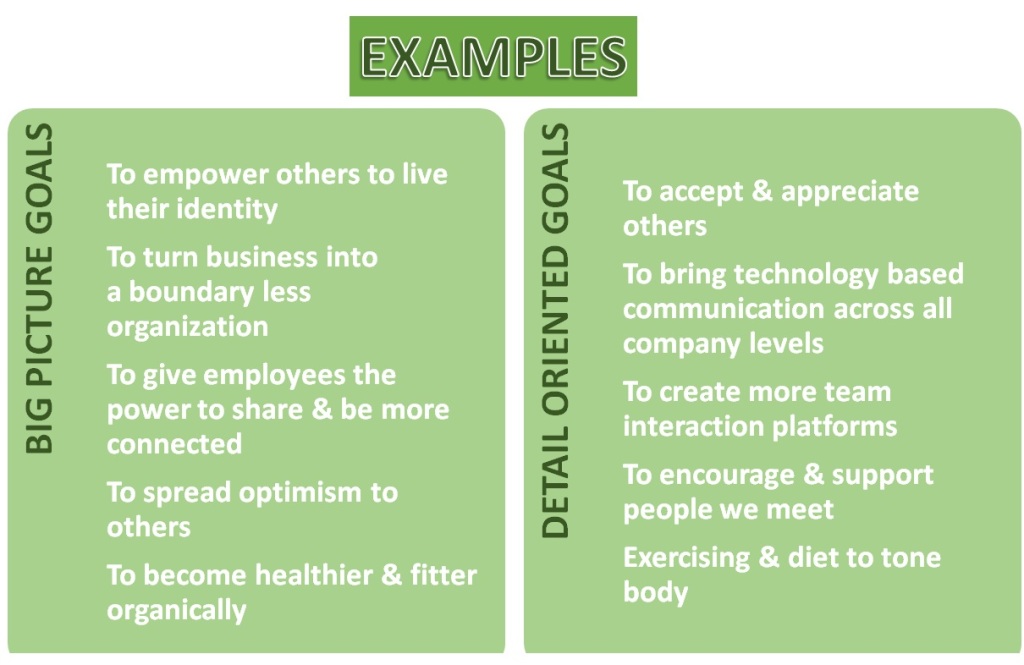

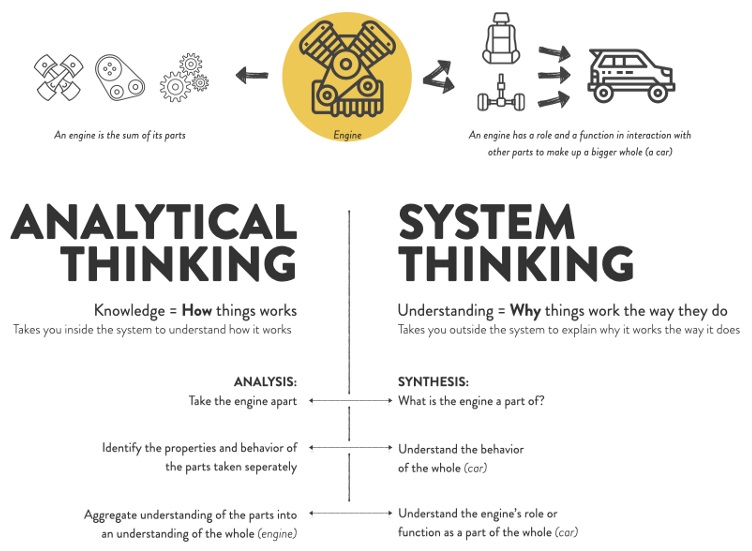

Analytical/ Linear Thinking Vs Systems Thinking

The Parts Of A System

Systems are made up of three parts: elements, interconnections, and a function or a purpose. The word “function” is used when talking about a non-human system, and the word “purpose” is used for human systems. The elements are the actors in the system. In our circulatory system, the elements are our heart, lungs, blood, blood vessels, arteries, and veins. They do the work. The interconnections would be the physical flow of blood, oxygen, and other vital nutrients through our body. The function of the circulatory system is to allow blood, oxygen and other gases, nutrients, and hormones to flow through the body to reach all of our cells.

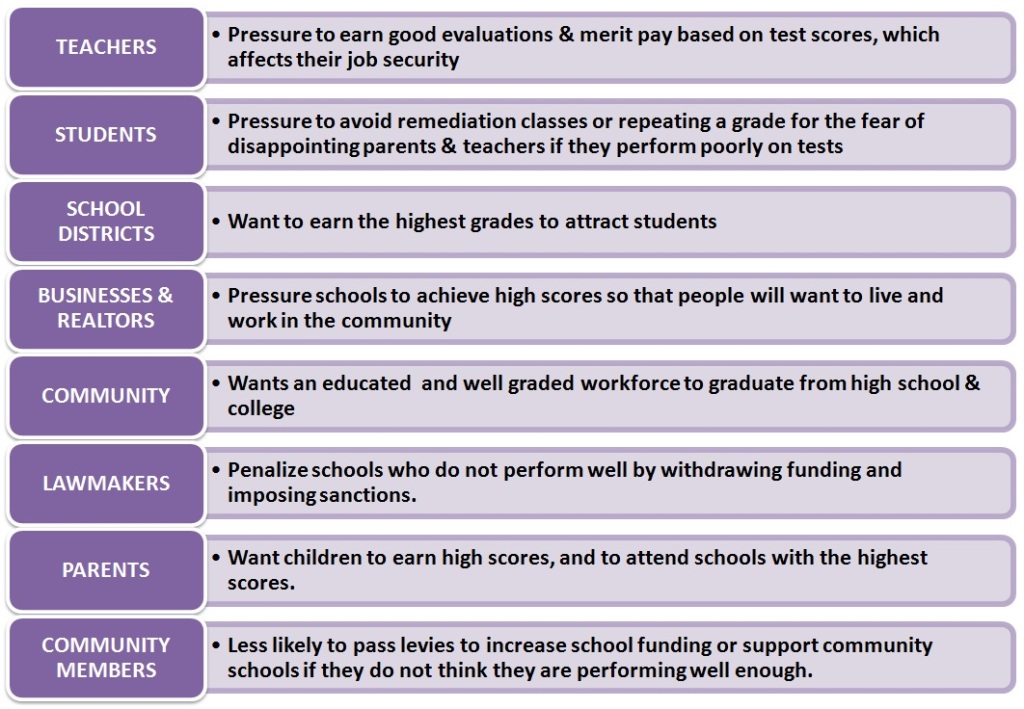

An Example – The School (or) An Educational Institution

A school is a system, with the elements represented by teachers, students, principals, custodians, secretaries, bus drivers, cooks, parents, and counsellors. The interconnections are the relationships between the elements, the school rules, the schedule, and the communications between all of the people in the school. The purpose of a school is to prepare the students for a successful future and to help them reach their full potential.

Unfortunately, some unintended behaviours can occur as a result of Organizational Change when the Systemic interplay is ignored. Consider the purposes of the actors in this system:

In this system, the high-stakes nature of the tests cause school districts to put a lot of pressure on their teachers to teach to the test and base their evaluations on their test scores. Teachers feel the need to compete with one another to earn the highest scores, as well as gain job security and an increased salary, so they no longer share ideas with one another and they may even cheat when administering the tests. Students feel a lot of pressure to earn high enough scores to be promoted to the next grade or avoid remedial classes, so they may cheat on the test.

A government may profess that educating children is a high priority, but if it slashes education funding, then clearly educating children is not a primary purpose of that government. This was not the intention of putting these tests into schools, and everyone agrees that those results are awful. Unfortunately, if the sub-purposes and the overarching system purpose are not aligned and coexisting peacefully, a system can’t function successfully.

The Most Important Part of a System

Perhaps the easiest way to examine how a system’s elements, interconnections, and purposes compare in terms of importance within a system is to speculate how the system would be impacted if each component was changed one at a time.

The least impact on a system is usually felt when its elements are changed. While certain elements may be very important to the system, by and large, if the elements are changed, the system can still continue to exist in a similar form and work to achieve its purpose or function. In a school, teachers, administrators, and other employees may leave, transfer, or retire. Students move away or may enter higher grade levels beyond the school. The elements may change, but the school is still easily identified as a school, and it still has largely the same objectives and sense of purpose.

Changing the interconnections of a system is quite different. If the interconnections change, the system will be impacted significantly. It may no longer be recognizable, even if the elements remain in place. Putting the students in charge instead of the adults in a school setting would undoubtedly change that system dramatically.

Changing a system’s function or purpose also greatly impacts the entire system and may render it unrecognizable. If the school’s main purpose is no longer educating children, but is now to make money by recruiting students to charge tuition, obviously the system is dramatically changed.

Every component of the system is essential. Elements, interconnections, and the purpose or function all interact with each other and each one plays a vital role in the system. The purpose or function of a system is often the least noticeable, but it definitely sets how the system will behave. Interconnections are the relationships within the system. When they are changed, the behaviour of the system is also usually altered. The elements are typically the most visible parts of a system, but are often the least likely to cause a significant change in the system unless changing an element impacts the purpose or interconnections as well. Each part of the system is equally important as they work hand in hand, but changing a system’s purpose has the greatest impact on the system as a whole.

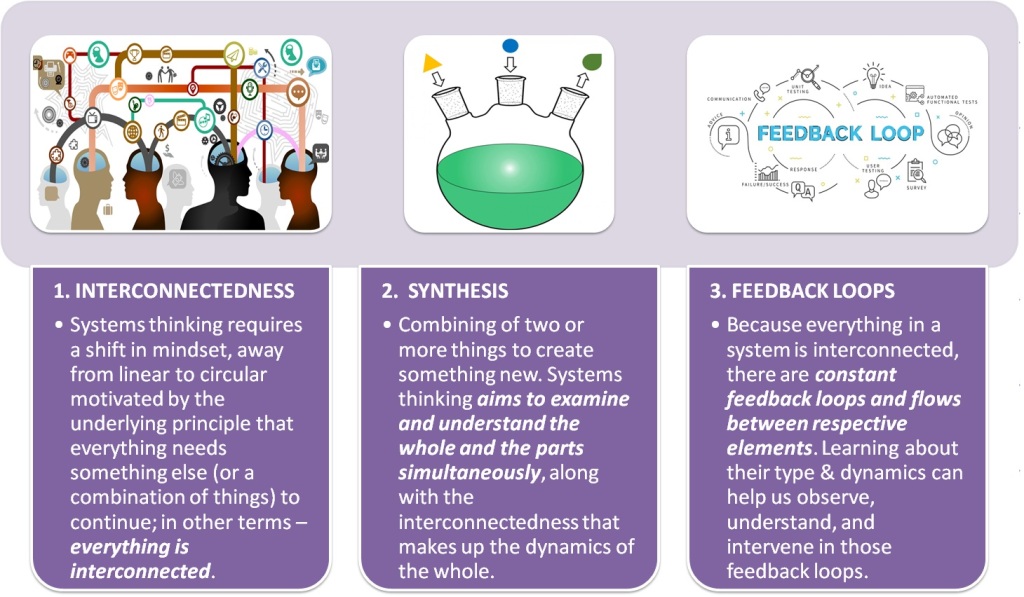

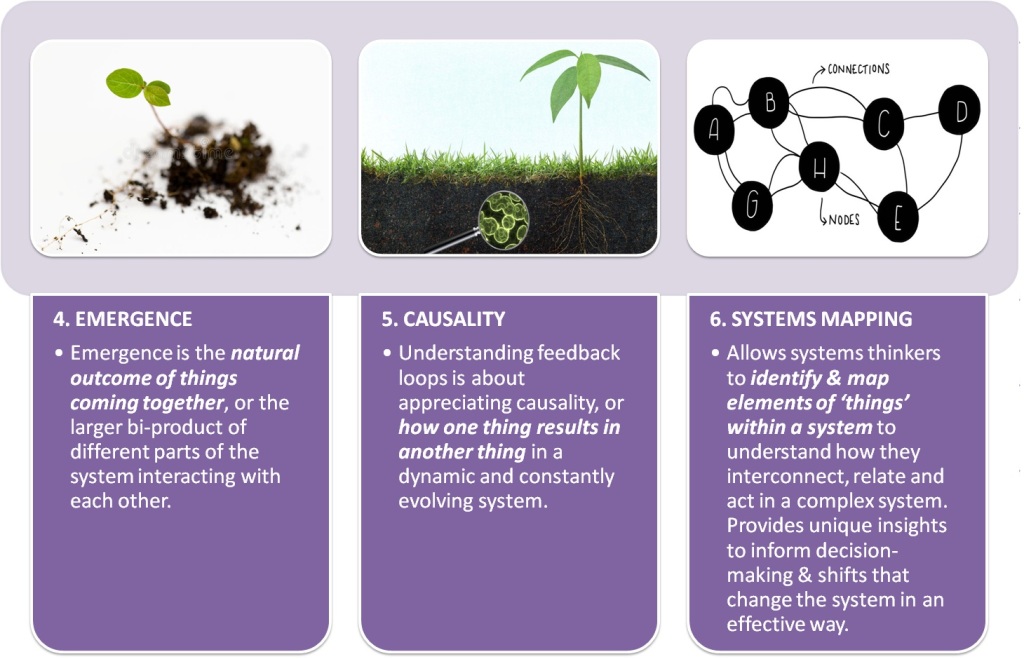

Six Themes Of Systems Thinking

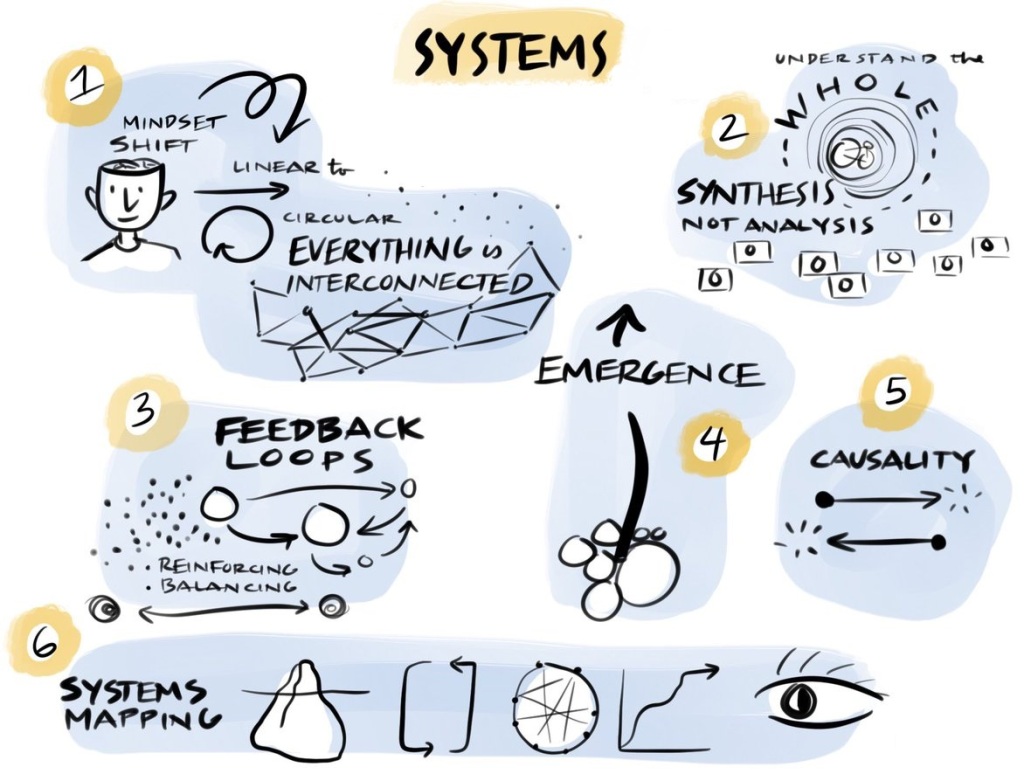

Interconnectedness and synthesis relate to the dynamic relationships between various parts of a whole, the process of obtaining expected synergies between parts of the company. This includes the idea of circularity, which stresses the requirement of a mindset shift from linear to circular. Similarly, the concept of emergence relates to the outcomes of synergies that can come about as the elements of a system interact with each other in nonlinear ways. In the workplace, this often takes the form of the push and pull that happens due to organizational politics and competing priorities. Organizational leaders with a systems-thinking mindset will see this as an opportunity for enhanced collaborations and innovation.

Balancing and reinforcing feedback loops within an organization serve as guidance for making adjustments as we learn more about the interconnectedness of the elements of the system and their outcomes. Additionally, causality refers to the flows of influence between the many interconnected parts within a system. As we better understand the casualty and directionality of these elements, we will have an improved perspective on the many fundamental parts of the system, including relationships and feedback loops.

In the workplace, a skilled systems-thinking leader will ensure that mechanisms for multiple feedback loops are established and effectively communicated to their employees. Furthermore, they will understand correlation versus causation as they use the data gathered from the feedback loops to enhance workplace practices. Finally, systems mapping is a tool that systems thinkers can use to identify and visually map out the many interrelated elements of a complex system, which will help them develop interventions, shifts, or policy decisions that will dramatically change the system in the most effective way.

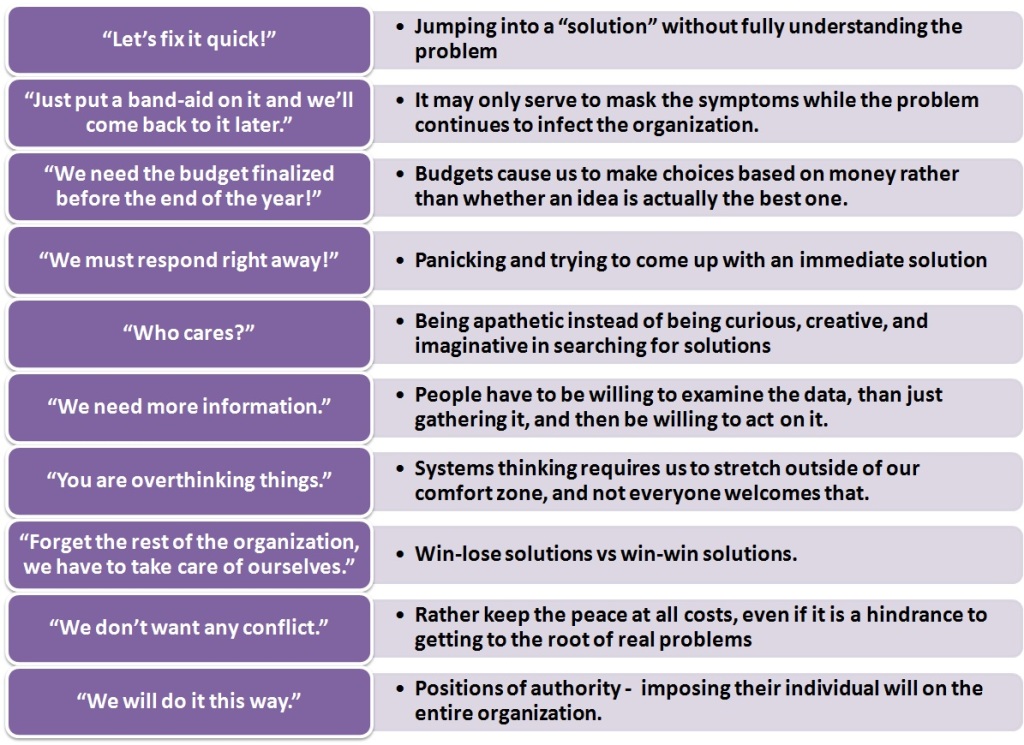

Ten Enemies of Systems Thinking

Some common thinking statements which act as obstacles to systems thinking may be:

Systems thinking does not come easily to everyone. Many find systems thinking to be a bit unstructured and unorganized when they first begin to look at the world through this lens. It may be overwhelming and uncomfortable at first because they become concerned about taking action when they don’t know the effect that their suggested solution may have on the system and its parts. Rest assured that this feeling is perfectly normal and will begin to ease over time as we reach deeper levels of understanding into the way systems behave.

The ultimate gain is the ability of organizations to be responsive to the changes in ecosystems and to be prepared to fine-tune and adapt parts of their organization on the fly. With this understanding, systems’ thinking provides clear benefits to organizations. It shows alternative directions for improvement with respect to the company’s inner and outer connections. It gives a significant advantage in increasing the organization’s capacity for change and, as a consequence, to fulfill the vision of business sustainability.

Content Curated By: Dr Shoury Kuttappa