“Company vision” might be the fluffiest business term thrown around by nearly every business book and article, often used vaguely, without nuance or thoughtfulness.

Yet despite its watered-down usage, “vision” is the most important information for us to communicate across a team. Research indicates that vision was ranked as the number one information people need to share in a team. Given its significance, how to best share a company vision within a team? Before we can answer that, we must start with what company vision exactly is and why it is important.

What is company vision?

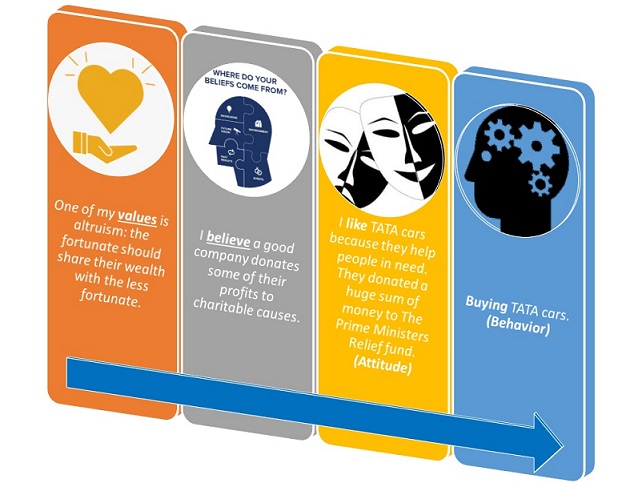

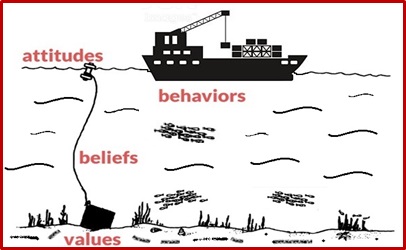

A vision is a picture of a better place. You see this picture in your head: It is what you want the world to look like because your product or team exists. In many ways, your team’s vision is your opinion on how you think the world ought to be. A vision answers the question, “What world do you want to create?” Vision is often misconstrued with other business terms, like “mission,” “purpose,” and “values.” But a vision is different from any of those things. A vision is what you want to create. The mission of your team is why you want to get to that vision. Your team’s values are how you want to get to that vision.

A company vision is a statement that outlines the long-term goals and aspirations of an organization. It is a powerful tool that helps define the direction of the company and provides guidance for decision-making. A strong vision statement can inspire and motivate employees, investors, and customers, and can help create a shared sense of purpose and identity.

Why does sharing a vision matter?

Sharing your company vision is important for four reasons:

- Clarifies decisions.

Many leaders strongly emphasise the importance of sharing vision as the ultimate tool for decision making. When the vision is clear, we give our team something explicitly to point to in decision making. The vision is the compass that all decisions are oriented around.

- Decentralizes decisions.

When the vision is shared across the team, each team member can have greater autonomy. Our team now has a shared destination on the map, so the manager doesn’t need to be ordering a series of coordinates instructing everyone how to get there. No more micromanaging. If we are clear about why we do what we do, our vision becomes a filter through which any employee can make decisions that align with who we are and what we’re about. But all of this is predicated on us as leaders regularly sharing this stuff.

- Alignment through disagreements.

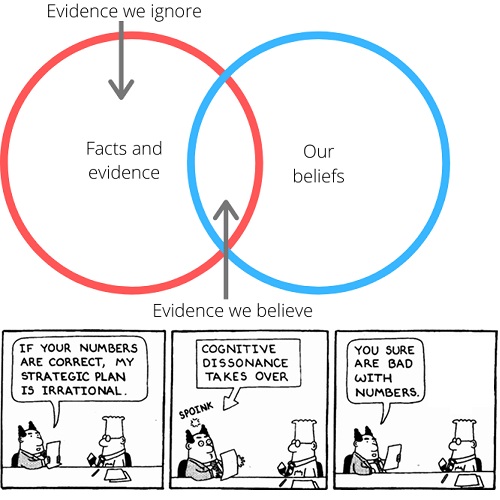

A shared vision also helps a team make decisions amidst disagreement. When people argue over how to grow the sales or whether to pursue a project, this shared vision is a uniting force that can override seemingly irreconcilable differences in opinion. It can also give our co-workers the courage to speak up and offer dissenting opinions since they know what the ultimate vision of the team is what they are trying to achieve.

- The greatest motivator for our team.

When shared, a company vision is the most powerful way to motivate a group of people. It gives the team a common place to strive for. When each person clearly sees that same picture of a better place in their own minds’ eye, each person connects to it and feels that pull of motivation to want to create that place.

Here are three thoughts we can consider:

- Over-communicate vision at all-team meetings

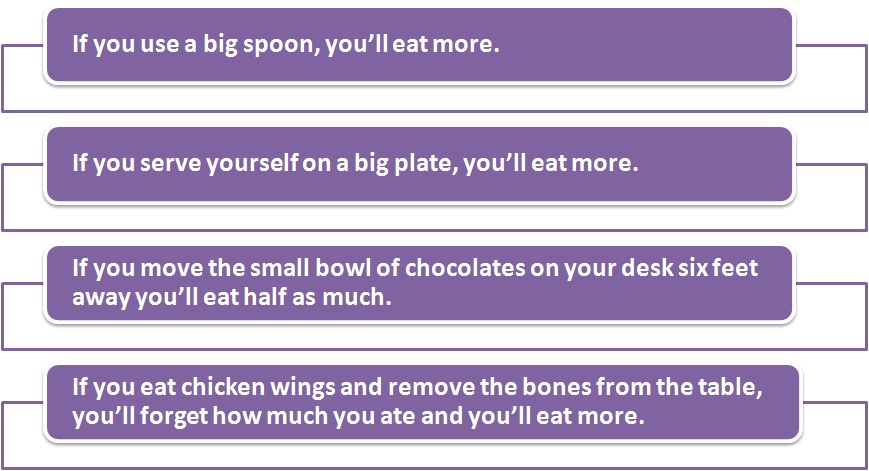

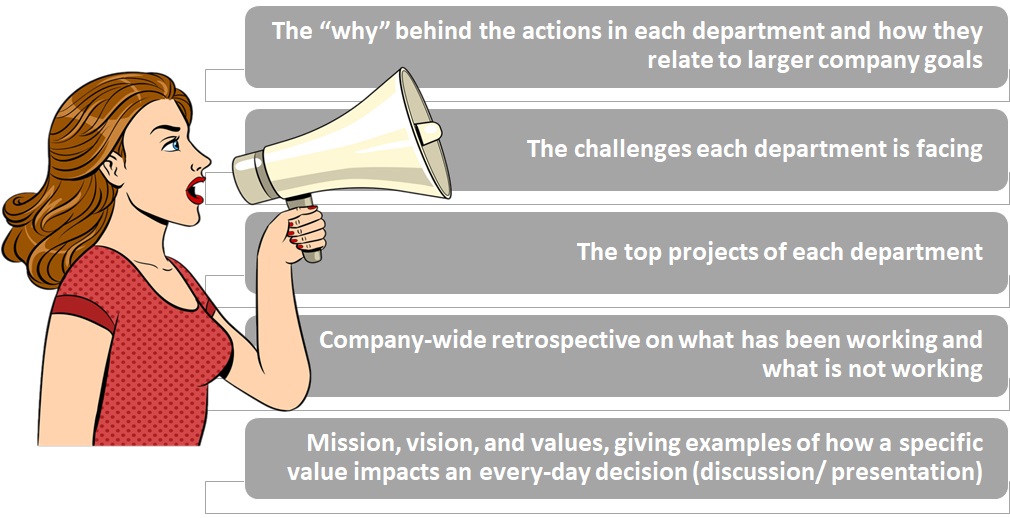

The most common way to share company vision is to utilize team meetings. All-team or all-company meetings are an ideal opportunity to have this discussion: Everyone is present, and you are carving out time to talk about broader team and company issues. Regardless of the frequency, the most important thing is that we hold some sort of regular all-staff meeting and that we make a discussion of vision a part of it. Specifically, at these meetings, the team’s vision can be discussed in the following ways:

What is most important is to not make these meetings a progress update. It is found that employees often feel they know what their co-workers are working on, for the most part. Make communicating the vision the focus.

- Leverage the one-on-one meetings.

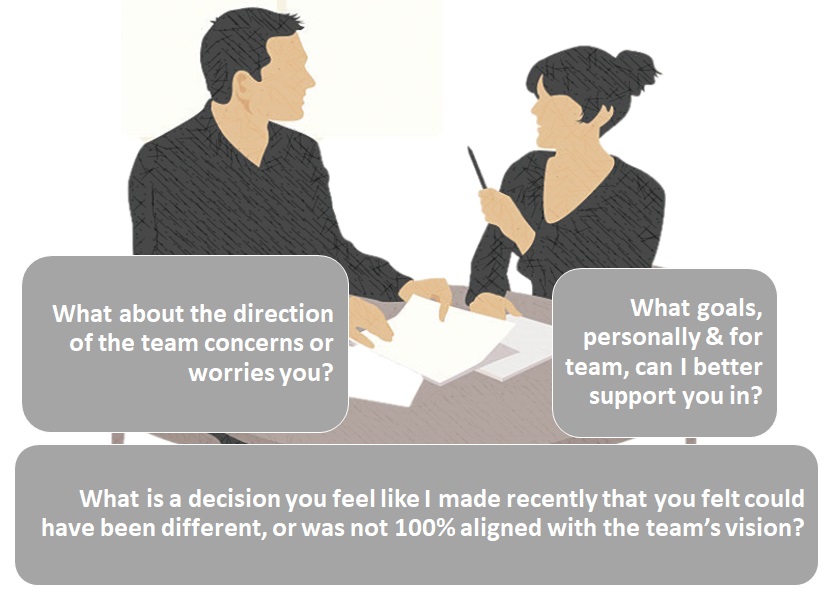

Communicating the vision isn’t just about broadcasting the vision: “This is the vision, and you must be on board…” Rather, sharing company vision should be a conversation. After all, a vision that is shared across a team is only built from the personal visions of everyone.

To do this, you will want to discuss the team’s vision during one-on-one meetings with the team members. For example, we can ask:

- Do not just talk about vision — codify it.

Talking about company vision during team meetings is great — but we should go beyond that as well. Leaders often present the vision to be something that developed organically and is discussed when needed. Documenting (codifying) the vision is another method on how to share the company vision. In particular, most teams seem to use an internal wiki or Google Docs to document and share the company vision. This often takes the form of a “culture book” or a few pages of their employee handbook.

As fluffy as the word “vision” can be, it can also be powerful when used effectively.

Content Curated By: Dr Shoury Kuttappa