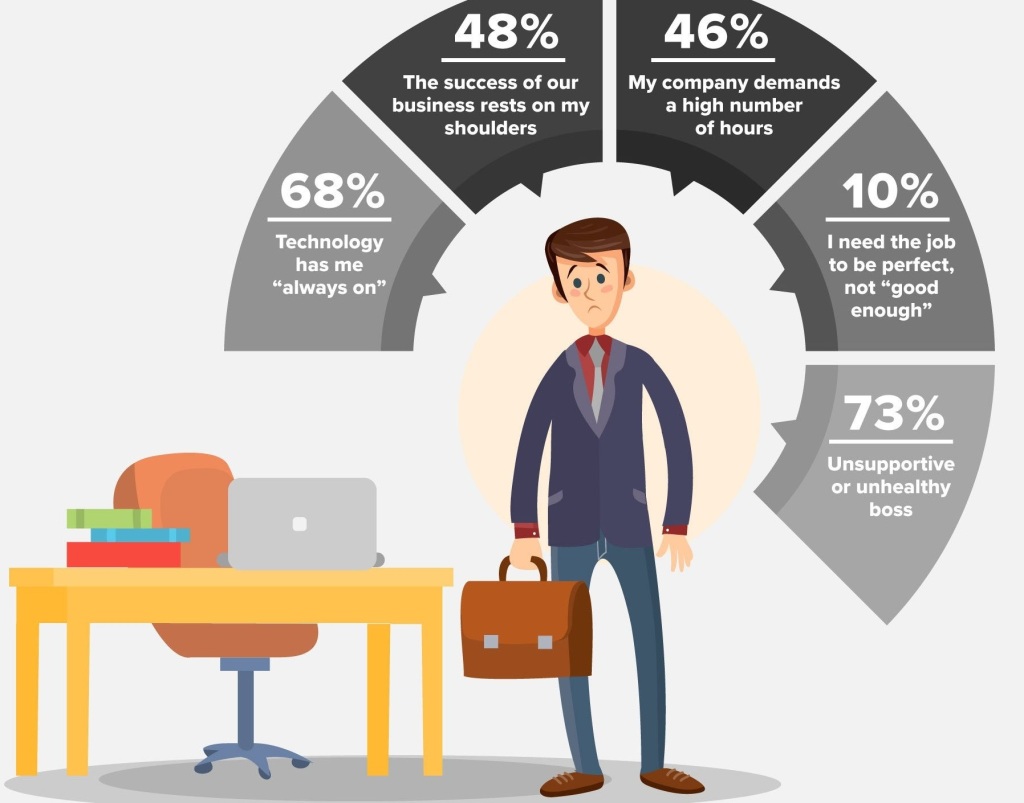

Work-life balance is the state of equilibrium where a person equally prioritizes the demands of one’s career and the demands of one’s personal life. Why is it so hard to maintain a balance? A survey of thousands of working adults found these to be the most common answers:

Work-life balance is less about dividing the hours in our day evenly between work and personal life and, instead, is more about having the flexibility to get things done in our professional life while still having time and energy to enjoy our personal life. There may be some days where we work longer hours so that we have time later in the week to enjoy other activities.

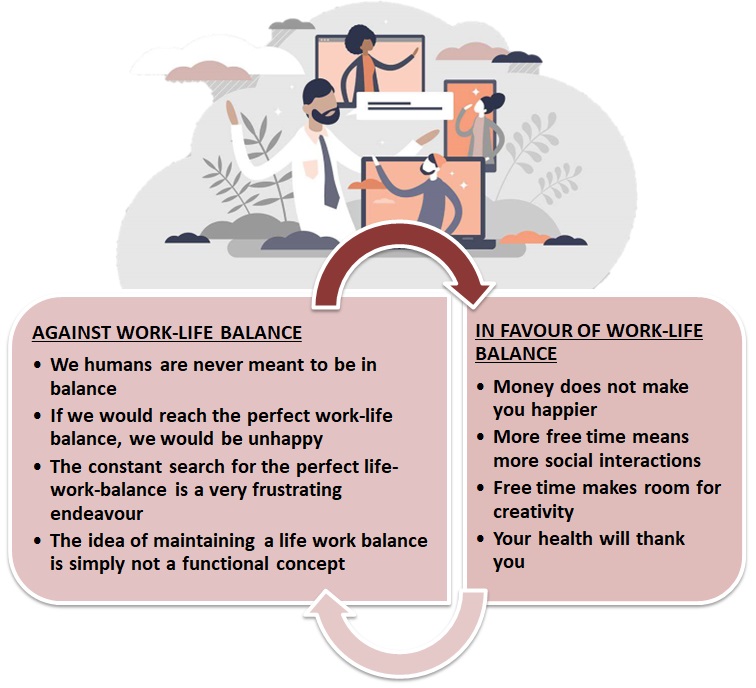

So far, it always seemed that finding a good balance between our daily work and the time we spend with family, friends or just ourselves is what we all should strive to achieve. Some arguments against and in favour of the work live balance theory may be:

When the focus is on business development, employers inevitably lose focus on where to draw the line regarding these practices. Let us look at what could happen when flexible working is not monitored well.

A) . . . -> Development of a complacent attitude

It is important to build a rapport with our employees by understanding their personal issues and granting them a leeway to work around them. However, it’s equally important for employers to know where to draw a line. When there’s freedom to work at individual schedules suiting employee needs, there’s room to take advantage, by not being productive, for example. Similarly, the many short breaks employees are allowed to take may turn into long ones, and the easy grants to take unplanned leaves will result in their absence from the desk too often.

If we are not building a system of measurement to monitor some of these benefits, it may result in the employees developing a complacent attitude towards the job. Consequently, this leads to lower productivity, lack of ownership and accountability.

B) . . . -> Lack of communication and innovation

One of the most common challenges faced by employers who have a team working remotely is communication. While the reasons are genuine most of the time, the employee can make a habit of such issues. For instance, an employee working from home might be situated in a ‘bad phone network’ zone – thus, reaching out to them becomes challenging. This results in confusion and possible delays in completing the assignments. Similarly, there may be poor internet connection or electricity problems – common problems of today which makes the remote working option very inefficient.

C) . . . -> Distractions and missed collaborations

Often, employees promise that they will manage work from home and stick to deadlines but are unable to do so due to genuine reasons. Be it due to having a pet or having constant distractions with a large family in the house, such employees are bound to be interruptions that won’t let them concentrate on their work.

An employee who enjoys scheduled flexibility can work perfectly well in his or her comfort zone if the project is being handled individually. But in the case of a group project, where one team member’s task depends on another’s, there’s bound to be a setback. As leaders we need to give these aspects a thought and understand that while it’s important for us to help employees work better, it’s also equally essential that we ensure the work-life balance is equally balanced. It’s always better to work smart than to work hard.

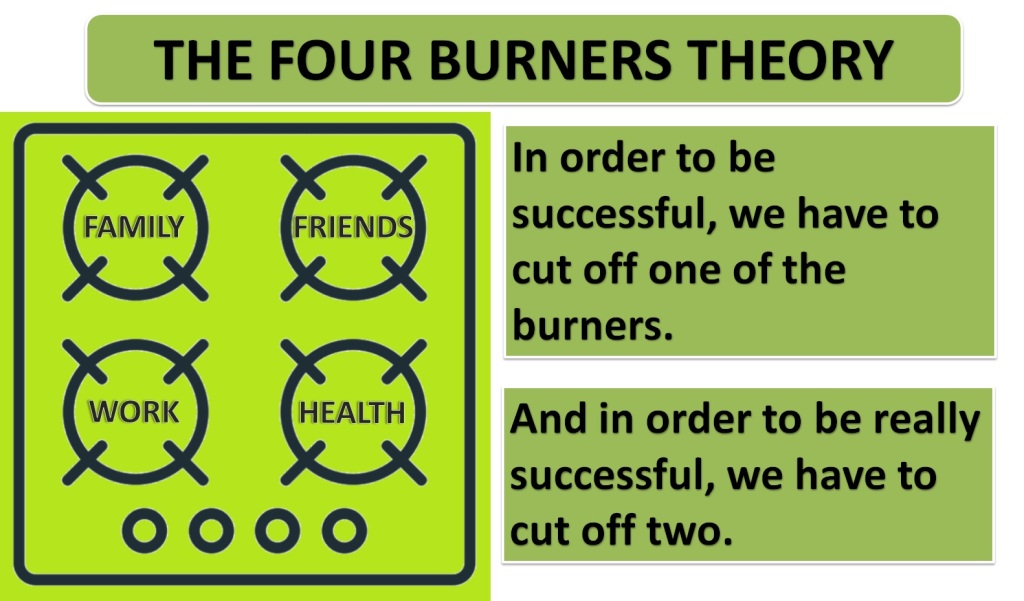

One way to think about work-life balance is with a concept known as The Four Burners Theory. Imagine our life is represented by a stove with four burners on it. Each burner symbolises one major quadrant of our life. The first burner represents family, the second burner is our friends, the third burner is health and the fourth burner is our work.

Which two would we choose? It’s a really difficult choice. If we decide that family and work are the most important — then we need to sacrifice our friends and health. If we decide family and friends are the most important — then we need to sacrifice our career and health.

Is there a way to side-step it. Can we succeed and keep all four burners running? Perhaps we could merge two burners. What if we grouped family and friends into one category? Or maybe we could combine health and work. We hear sitting all day is unhealthy. What if we got a standing desk? Believing that you will be healthy because you bought a standing desk is like believing you are a rebel because you ignored the fasten seatbelt sign on an airplane.

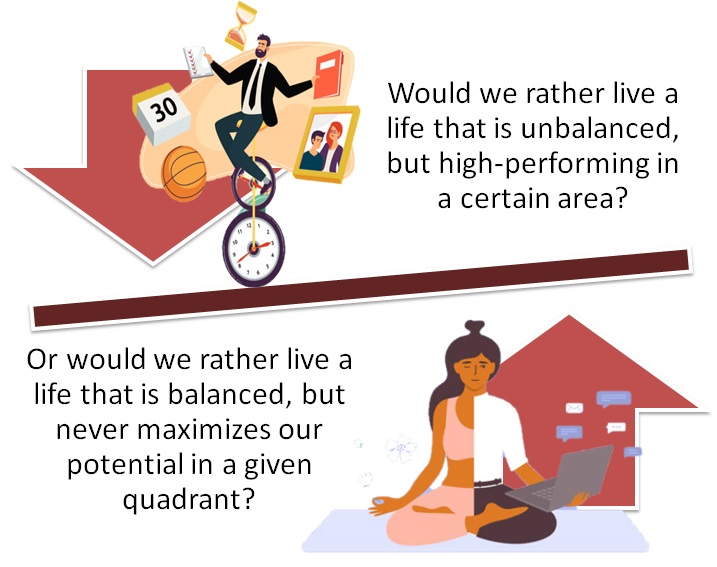

Overall, life is all about trade-offs. If we want to outperform in our work and in our marriage, then friends and health may have to suffer. If we want to be healthy and succeed as a parent, then we might be forced to let loose our career ambitions. We are free to divide our time equally among all four burners, but we have to accept that we will never reach our full potential in any given area.

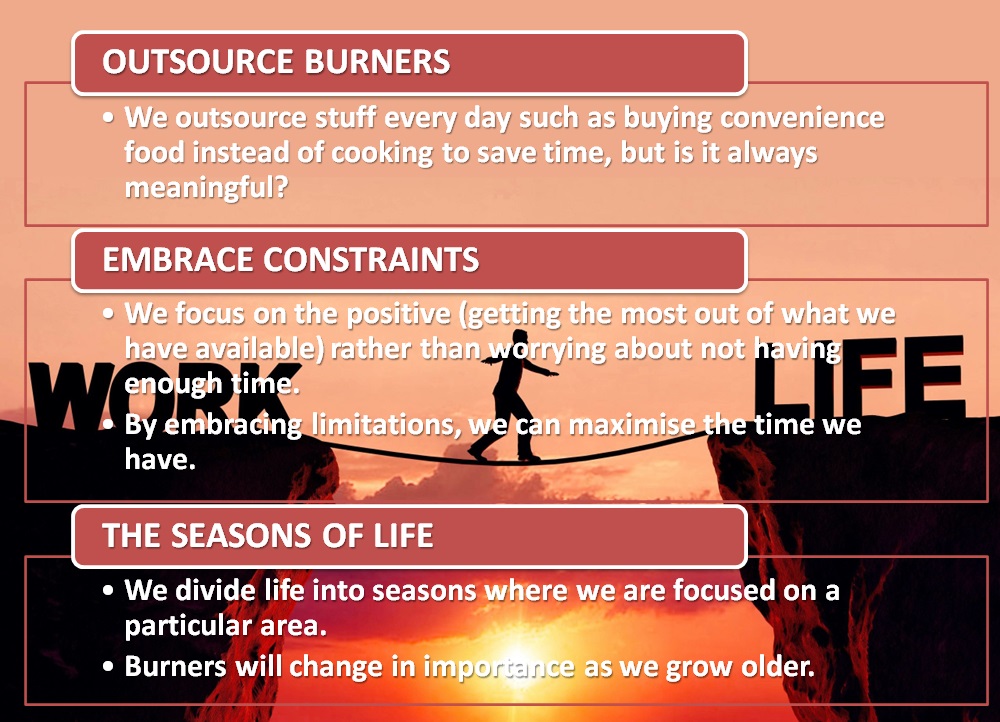

What is the best way to handle these work-life balance problems? Here are three ways of thinking about The Four Burners Theory.

Option 1: Outsource Burners . . . ->

We outsource small aspects of our lives all the time. We buy fast food so we don’t have to cook. We go to the dry cleaners to save time on laundry. We visit the car repair shop so we don’t have to fix our own automobile. Outsourcing small portions of our life allows to save time and spend it elsewhere. Can we apply the same idea to one quadrant of our life and free up time to focus on the other three burners?

Work is the best example. For many people, work is the hottest burner on the stove. It is where they spend the most time and it is the last burner to get turned off. In theory, entrepreneurs and business owners can outsource the work burner. They do it by hiring employees.

Parenting is another example. Working parents are often forced to “outsource” the family burner by dropping their children off at day-care or hiring a babysitter. Calling this outsourcing might seem unfair, but—like the work example above—parents are paying someone else to keep the burner running while they use their time elsewhere.

The advantage of outsourcing is that we can keep the burner running without spending our time on it. Unfortunately, removing ourselves from the equation is also a disadvantage. Most entrepreneurs, artists, and creators would feel bored and without a sense of purpose if they had nothing to work on each day. Every parent would rather spend time with their children than drop them off at day-care. Outsourcing keeps the burner running, but is it running in a meaningful way?

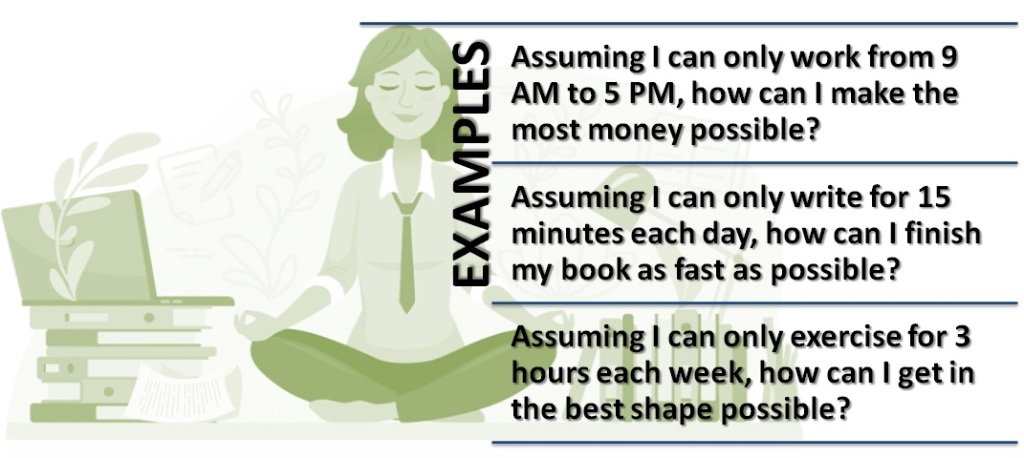

Option 2: Embrace Limitations. . . ->

One of the most frustrating parts of The Four Burners Theory is that it shines a light on our untapped potential. It can be easy to think, “If only I had more time, I could make more money or get in shape or spend more time at home.”

One way to manage this problem is to shift our focus from wishing we had more time to maximizing the time we have. In other words, we embrace our limitations. The question to ask ourselves is, “Assuming a particular set of limitations, how can I be as effective as possible?” Some examples may be:

This line of questioning pulls the focus toward something positive (getting the most out of what we have available) rather than something negative (worrying about never having enough time). Furthermore, well-designed limitations can actually improve performance and help stop procrastinating on goals.

Embracing limitations means accepting that we are operating at less than our full potential. Yes, there are plenty of ways to “work smarter, not harder” but it is difficult to avoid the fact that where we spend our time matters. If we invested more time into health or relationships or career, we would likely see improved results in that area.

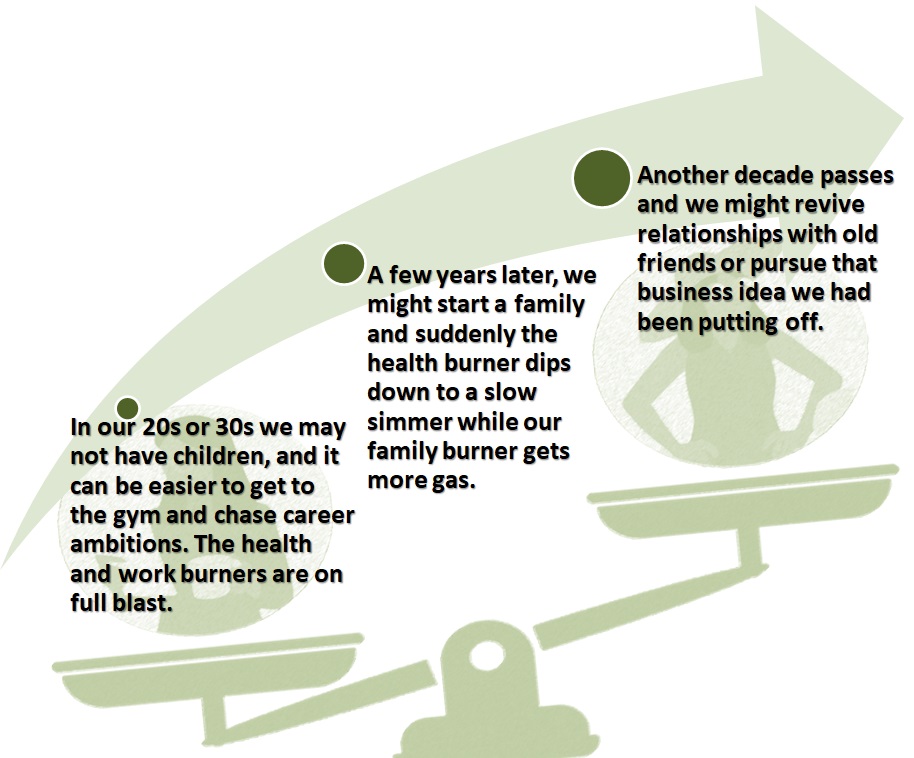

Option 3: The Seasons of Life . . . -> A third way to manage the four burners is by breaking our life into seasons. What if, instead of searching for perfect work-life balance at all times, we divide our life into seasons that focused on a particular area? The importance of our burners may change throughout life. For instance:

We don’t have to give up on our dreams forever, but life rarely allows to keep all four burners going at once. Maybe we need to let go of something for this season. We can do it all in a lifetime, but not at the same time. Furthermore, there is often a multiplier effect that occurs when we dedicate ourselves fully to a given area. In many cases, we can achieve more by going all-in on a given task for a few years than by giving it a lukewarm effort for fifty years. Maybe it is best to strive for seasons of imbalance and rotate through them as needed.

The Four Burners Theory reveals a truth everyone must deal with: nobody likes being told they can’t have it all, but everyone has limitations on their time and energy. Every choice has a cost.

Some people may even disagree with the fact that to be successful (however we define that) we need to turn off one burner and to be really successful, we must turn off two. Perhaps instead of turning the burners off we can turn them down a little and adopt the seasons of life approach. This seems like a more balanced approach than turning off at least one quadrant completely. For instance, the people of Denmark are consistently ranked amongst the happiest people in the world. They work shorter weeks, explore the outdoors and spend quality time with friends and family.

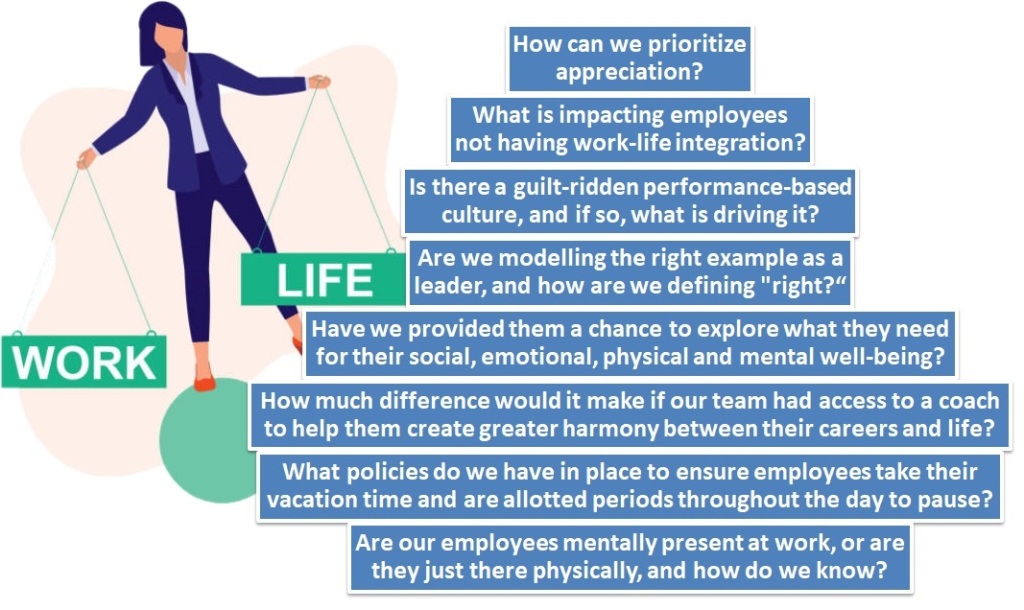

A good work-life balance has numerous positive effects, including less stress, a lower risk of burnout and a greater sense of well-being. Employers that offer options as telecommuting or flexible work schedules can help employees have a better work-life balance, and can save on costs, experience fewer cases of absenteeism, and enjoy a more loyal and productive workforce. Below are some reflective questions to get started within organisations:

Content Curated By: Dr Shoury Kuttappa